I’m not an 18xx aficionado. To tell the truth, I’m not even much of a train gamer. Besides a single play of 1830: Railways & Robber Barons (which I didn’t enjoy) and a handful of attempts at Age of Steam (which I’m slowly warming up to but still far from in love with), my experience when it comes to train games is mostly limited to the two Brasses, Maglev Metro, and simpler titles like Ticket to Ride or Trans America. So why should someone like me be interested in Railways of the Lost Atlas? Well, I can mostly blame/credit Ben of Game Brain / Table Scraps fame for this one. On various episodes, he kept raving about how great it is and that got me curious.

Finding a copy wasn’t easy though! Newly formed publisher Asterisk Games had run a successful Kickstarter campaign, but it’s the type of item where if you’re going to spent money on it in the first place, you will keep it. A couple of weeks ago though, I finally found someone willing to part with their copy.

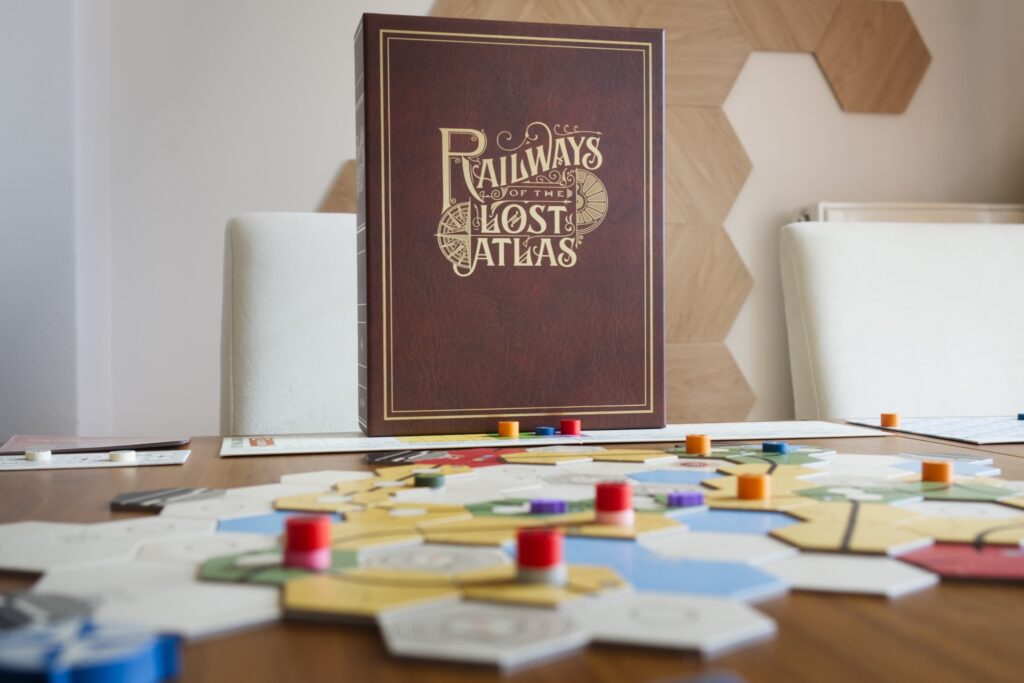

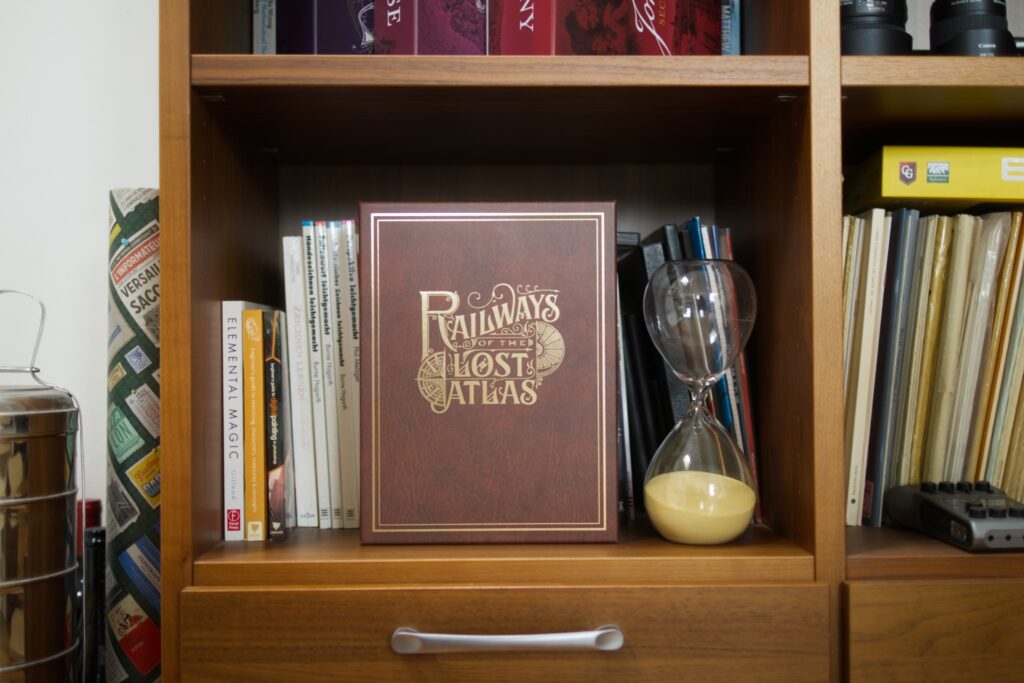

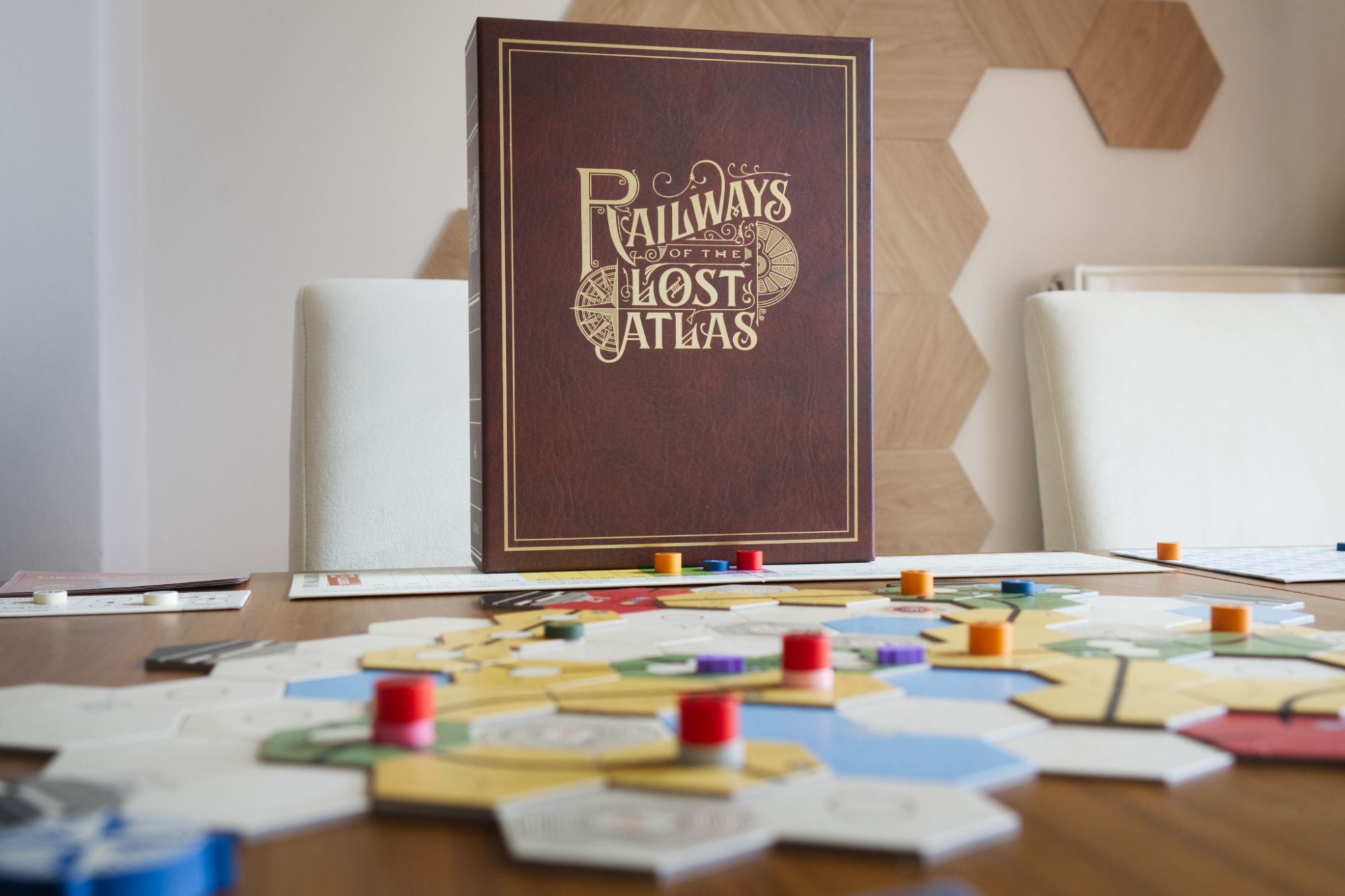

Unboxing

I’ve written before about how the experience of playing a game doesn’t just start with the first turn but everything before it: how enticing the box and components look, how easy it is to learn the rules, how tedious setup is, etc. I mention this here because Railways of the Lost Atlas already put me in a good mood as soon as I brushed the packaging material away and lifted its box out of the parcel. That cover is just class and feels at home in a nice old private library full of treasured books.

Opening the rulebook continued this warm feeling. The rules are well written, nicely illustrated, and with no gram of fat on them … so much so that players new to the system that is 18xx can easily miss important nuances here or there on first read. The components look clean but somehow charming and elegant, the wooden pieces are screen printed, and there is even card money instead of paper money, removing the need to break out those poker chips unless you really want to. The rules contain a number of variants to adjust the game to a group’s likings which in most games would be a sure sign of the designers not having playtested their game enough to be able to tell what the best version of their game is. But here it somehow manages to convey that one is always getting a full, rich experience with the base game and these are just things to dabble in if one wants to or already has extensive experience with 18xx. The box is filled to the brim and leaves one with the feeling of having purchased a nice, well thought out product made by people intimately familiar with the genre.

Setup

Right from the get go, Railways of the Lost Atlas flexes two traits that are among the main reasons why backers were interested in this game: variable play length and map building. I don’t remember the length of my single play of 1830, but I believe it was north of four hours, not counting the teach! That puts it firmly in “event” territory, something you need to plan for. For me, this is a knock out criterium for 1830 because if I can convince my friends to meet up for an epic session of board gaming, there are a whole bunch of other titles (Hegemony, Indonesia, John Company 2nd Edition, The Colonists, …) I would prefer to get to the table over something like 1830. My experience with it was just too painful and had dragged on far beyond what I wanted it to.

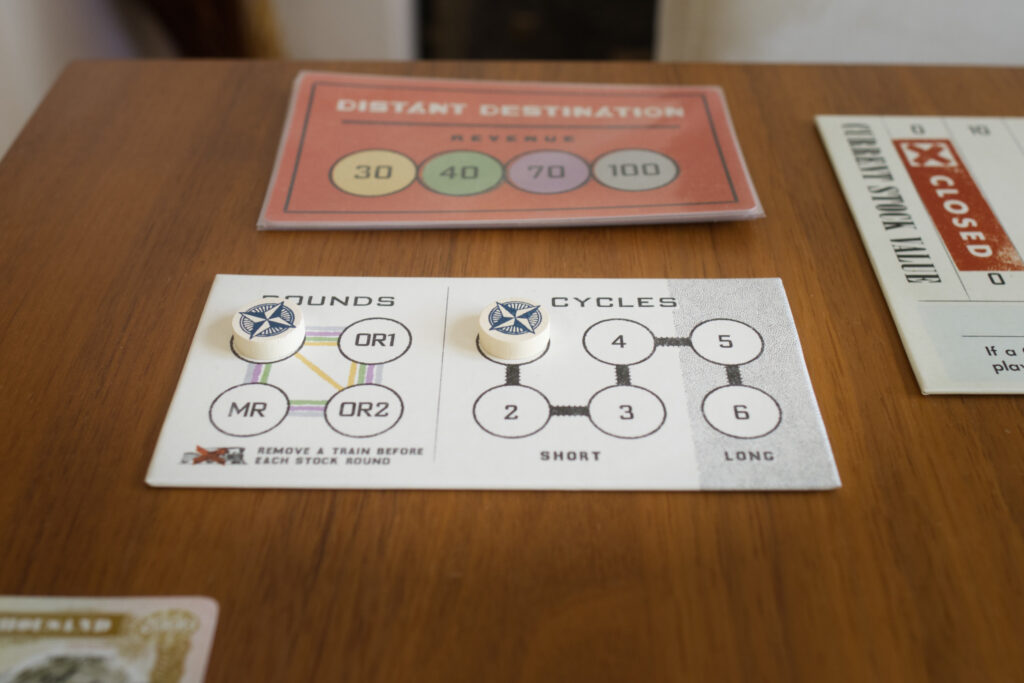

Railways of the Lost Atlas on the other hand features a short (=4 “cycles”) and long (=6 cycles) version as well as a micro mode. For the short game, the size of the map, trains for purchase, and number of available companies are reduced but there are no other major changes. This pushes play length into the 2 to 2 1/2h territory and turns 18xx into something that can be pulled out on a school night. The micro game variant is intended for low player counts and/or as an intro for new players.

As to the map building, it is the only setup required except for giving each player their starting money and laying out a few shared components. The map tiles (clusters of 3 hex tiles) are shuffled and one by one players add them to the growing map. There are a few minor rules like that black hexes are not allowed to touch other hexes, but otherwise it’s completely left to the players to build a map to their liking. Similar to Rise & Fall, this is fun and rather quick to do but of course puts players into the position to have to make sure a somewhat balanced map is created. Easy to do if you’ve played the game once or twice before, but on first play, there will naturally be some companies that end up having a better starting position than others. This unbalance is usually offset by players bidding on companies, but properly evaluating what a company might be worth is equally hard for new players.

One clever tidbit are the project tiles, map tiles that are shuffled into the stack but don’t get added to the map themselves. Instead, the player that draws one chooses a city that is upgraded to a more valuable capital (a circle with a star in it). The project tile itself is then discarded and the next player continues drawing the next tile from the stack. In the announced upcoming expansion, this mechanism is used to integrate more unique tiles and shapes to the map as well.

Game Structure

If you haven’t played an 18xx-style game before (e.g. 1830, 1846, 18Chesapeake, …), the round and turn structure might seem a bit daunting at first but is actually quite simple. Railways of the Lost Atlas is played over 4 or 6 “cycles”, each of which is split into four rounds. The initial stock round (SR) is where players bring new companies to the map or trade stocks in them, the two operating rounds (OR1 & OR2) is where the player that currently holds the most shares in a company (called the president) lays tracks as well as runs the trains of that company to generate earnings to be distributed among the share holders, and finally there is a merger round (MR) where companies can potentially join forces. So this is one of these games where a player doesn’t really own a company but rather has private capital that they can invest into shares and thus gain control of a company. At the end of the game, all shares are liquidated and the player with the most money wins. Easy, right?

The other important bit to know is that the game progresses in eras—from yellow to green to purple to grey—which will have an impact on which track tiles can be built and which trains purchased. Or to be precise it’s rather the other way round. During setup all train cards are put in an open stack of increasing level. Early trains can only connect two cities but are rather cheap, later ones can connect five or more but can cost an arm and a leg. If a player purchases the first train of a new level, certain elements of the game change such as older trains becoming obsolete which in 18xx parlour affectionally is called “rusting”.

All 18xx games are built around a similar core of track laying, earning money, and trading shares, but each one adds its own tweaks and maps to the core formula.

Stock Rounds

Let’s start talking about Railways of the Lost Atlas by looking more closely at stock rounds, which as mentioned before serve two main purposes: bring new companies into the game and trading stocks. On a player’s turn, they can do either one of those or pass. When all players in a row have passed, the stock round is concluded.

Starting a new company is simple: pick one of the available so called “minor” companies, make an opening bid of at least 120, and choose one of the available for auction companies. Railways of the Lost Atlas has two special traits here that set it apart from 1830: each minor has a “power”, some special effect or lucrative starting position that other minor companies don’t have. E.g. there is a single minor that can build bridges over water, one that gets a bonus for tunnelling through mountains, one whose trains travel slightly further, etc. However, only 2 (or 3 in the long game) are up for auctioning at any point in time. During setup, all minors are shuffled and placed into spliced columns, with only the top-most being available.

The big question is of course how much to bid for a given company? Well, that depends. Paying less leaves more money for other investments. Paying more results in a higher initial stock price which puts the company earlier in turn order. Depending on the map layout, that might be quite important. Then there is of course the question of how much potential you see in a company generating lots of money over the course of the game and finally there is the question of liquidity. The winning bid is placed into the companies treasury, not the bank, so a higher bid allows it to more quickly buy higher level trains or tunnel through expansive mountain regions.

Trading stock on the other hand has a couple of nuances, explaining all of which would go too far here. The gist is: you buy stock in companies you might want to gain control of or want to have a larger share of earnings in, while selling those that don’t turn out profitable enough or where selling hurts the least if you’re simply wanting for cash. A single player can at most hold 60% of the shares in any one company and whoever has the most becomes new president. This sounds rather Euro-y tame, but that’s far from the truth! A particularly nasty move is to suddenly pull all the trains out of a company, sell your shares in it and make the player with the next most shares the new president. Since no company is allowed to stay without a train, the new president will have to buy the company a new train, out of their own pocket if necessary.

Operating Rounds

But how to earn money in the first place you might ask? 18xx splits money into that which belongs to players and that in the treasuries of the individual companies. Companies use their money to buy new trains, build new hubs, dig tunnels, or buy back shares. Players pretty much exclusively use their money to buy shares in companies, except for the aforementioned case of being forced to buy a train for an insolvent company. Players—even presidents—can’t just pull money out of companies and they also can’t just pitch in at will if the company needs a few more bucks for some investment.

During each of the operating rounds, companies are processed in order of decreasing stock value. The president of a company can lay new tracks (which don’t cost any money at all except when building through mountains), establish new hubs (to open up possibilities for new routes), buy new trains, and run those trains to earn money. One important detail here is that normally buying trains is the last action in a company’s turn. However, to speed up the flow of the game, Railways of the Lost Atlas makes an exception for the so called “lead train”, the first ever train a company needs to buy. That one can be bought at the start of the turn so the company already has something to run during it’s first OR of existence.

Running trains is rather simple: each train has a number printed on it how many cities it can connect. Trace a route of connected cities via the rails on the map and make sure one of the company’s hubs is part of it. Each city has a value printed on its tile and adding up all the values on the route produces the earnings for that train in that round. Of course there are some limitations, the most annoying one being that a route cannot run more than once over each piece of track. That doesn’t sound too bad at first but makes placing junctions correctly quite critical. You can’t just drive into a city one way and then leave the city over the same junction to go somewhere else.

Merger Rounds

If the game has progressed to at least the green era of trains, the cycle ends with a merger round where presidents of minor companies can propose mergers with other minors. The way this is implemented is one of the cutest, most satisfying parts of the whole game. A merger is just moving the two minor cards next to each other, choosing one of the available major company name and colours, and then placing that card over the two minors. This forms something like the “Expansive Tunnelling Syndicate” or the “Suburban Agriculture Conglomerate”. The major cards are even double sided for no other purpose as to give players more options of fancy names. Lovely!

The shares of the minor companies are exchanged against shares in the new major company, trains and treasuries merged, and the hubs replaced by ones from the major company. That’s it. The new company now has the special traits of both minor companies and can continue to earn more money.

Merging not only has the benefit of now only having to worry about one (instead of two) companies to not have all of its trains rust away, it also keeps the flow of the game up. Instead of having to manage more and more minors as the game goes on, the number of overall companies stays rather the same. One thing I found to have less impact than I initially thought was which specific two minors to merge. The combination of purchased trains and accessible railway network is definitely more important than combining two particular company powers.

… And Then There Are All The Shenanigans

So far, so simple. Bid for companies, lay tracks, build profitable routes, get more modern / longer distance trains, invest in the right companies. It all sounds like a nice, wonderful train set to play with. Or like constructing profitable networks in the old PC game Railroad Tycoon.

But make no mistake: Railways of the Lost Atlas (or rather 18xx as a system) is mean! From people buying stock in your companies to then immediately dump it—all to just crash the stock price—to laying track upgrade tiles in a way that prevents others to connect to a valuable city to aggressively buying trains and causing those of other companies to rust more quickly to … I’ve glossed over lots of details in the explanation above (such as that trains can be bought from another company for a negotiable price), all of which seem to be designed for the sole purpose of messing with other players. That isn’t the designers’ fault, in fact they have integrated a lot of rules tweaks to make this as pleasant an experience as possible. But 18xx by nature is all about fighting the competition. Removing those aspects from the game would be like removing a tiger’s teeth before stepping into the cage. Just not the same and kind of pointless …

On the one hand, this makes the system of 18xx so interesting for repeated plays. Learning the ins and outs of when to pivot and how takes time, same as what to bid for a certain company and when rather to fold, knowing which track tiles simply don’t exist or only a single time. Stepping into 18xx has an almost wink-wink-nudge-nudge kind of feel, like there being things one has to learn one simply doesn’t do. But that of course makes it hard for new players. Any game that expects players to bid on something they have no clue about as the very first action of the whole game is hard to get into. Railways of the Lost Atlas with its rules and production does a great job of making it enticing to want to dive into it 18xx. But there is a good chance your first play will leave you frustrated if you don’t brace yourself for it.

Game End

The game ends once the last cycle is complete. All shares are liquidated based on the current stock prices and the player with the most money wins. Having a calculator for this definitely helps, but otherwise it’s as easy it sounds.

Solo Mode

As part of the upcoming expansion, Railways of the Lost Atlas will receive a solo mode! This is great news, especially for a game with a hard learning curve like an 18xx as it provides a safe space to familiarise oneself with the basic rules. One of the designers has posted a development thread on BGG and I’ve played the solo mode multiple times now. I really like it! It of course can’t capture all the stock trading aspects of the multiplayer game, but it does a very nice job of forcing you to deal with a strong opposing force and having to worry about correctly dealing with train rust.

In a nutshell, it uses the short version of the game (=4 cycles, smaller map) and pits the human player against an already existing major company. No additional components are needed, the stock cards of those two minor companies are used as an action deck and govern how the company will extend its network. One can play it either on the pre-made short version map that comes as part of the base game’s rules or construct one’s own map. I’m the wrong person to talk about difficulty as I have nowhere near as much experience with 18xx as other players. But so far, all my plays have been very enjoyable and I had different things to worry about. If the solo mode will be made compatible with the new unique map tiles of the expansion, that will make for a pretty sweet solo experience with much reason to return to it! Now that I’ve played the solo mode more, I kind of regret not having signed up for the playtesting of the expansion!

Conclusion

As I wrote in the introduction, I have only played 1830 so far, but I’m already pretty sure in saying 18xx is not for me. As much as I enjoy the economics of building profitable routes, all the worrying about whether I can buy a second share in a company or if it will result in someone dumping the company on me just spoils the fun for me. As a result, I feel more comfortable with an Age of Steam than an Iberian Gauge, and 18xx seems to turn both route building and stock trading up to eleven.

That makes it all the more remarkable that I do enjoy Railways of the Lost Atlas as much as I do. The production is super nice and inviting, the shortened play time makes it less of a pain if things go wrong, I don’t need to get 3-4 players together to have fun, and the variable map building puts players seemingly more on an equal footing, a bit like how the Freestyle / Fischer Random format is currently breathing new life into the chess world. Adding a solo mode only helps to win me over and definitely makes this a keeper for me.

My favourite part about Railways of the Lost Atlas is how much it feels like a labour of love. I can’t remember another package that felt so “complete” to me since Carnegie, one of my favourite games of recent years. It’s a crowdfunding project with a single tier (instead of adding unnecessary “deluxe” pledges), has great art design that isn’t over the top, rules that are well written and laid out, a compact box that’s easy to bring to a game night, multiple variants to adjust the gameplay to your hearts delight, works as a quick 2h intro or a 4+ hours event, there are even single hex tiles to fill gaps in the map … It hasn’t made me love the stock part of 18xx, but at least it has made me curious about exploring it more. And at the same time I have the solo mode and 2p game to provide me more of a safe space where I can just build routes and bid for new companies.

My second-most favourite part is how much the designers have managed to establish a good flow of the game. From lead trains and exports (removing trains automatically at the end of a cycle) to how the merger mechanic reduces the number of companies to operate, Railways of the Lost Atlas manages to remove most of the dread I experienced while playing 1830. It still hurts if someone dumps a company on you or when you make a critical mistake when laying tracks, but at least it won’t haunt you for the next 4 hours as the game drags on. And yet, if you’re familiar with the game, you can brake out the long version with its 6 cycles, multiple rusting, and so on. In some sense, Railways of the Lost Atlas feels like a “best of” album of 18xx, and that’s me saying that without having played almost any of them!

The only real “critique” I can think of is that the card money is quite slippery and the bank after a short time looks messy. But I still much prefer this to paper money although using Iron Clays is still my top choice. It is a bit annoying how often one has to exchange denominations to keep somewhat of an overview, what with 18 bucks earned here, 44 bucks earned there, but there is no real way around that one other than putting little abacuses in the box! And all the cards have bent from moisture quite a bit, but that’s fixable. One thing I would have wished for would have been even more of an intro variant. E.g. to have 2-3 pre-made maps for the short version with predefined company costs to remove the need for new players to immediately start arbitrary bidding. I know, I know, any 18xx pro will revolt as they read this. But as a new player sitting in front of a nice map you just made having no clue what to bid just feels wrong. The other thing I could think of would be a variant where if you’re once the president, you cannot involuntarily dump the responsibility to force-buy trains onto another player. But again I realise that that is part of the fun for those that love the system.

As you’ll notice, I’m already reaching here. Railways of the Lost Atlas is so well done, it’s hard to seriously fault it for anything. Some 18xx lovers will miss the historically accurate maps, but for me this is a plus. If you have any interest in train games AND stock trading at all, definitely jump on the expansion/reprint kickstarter when it launches! If you don’t like the stock part, I’d rather recommend Age of Steam, even if I’m personally not the biggest fan of it. If you just want to lay tracks and maybe block other players’ routes, you’ll probably be best served with something like the recently released Steam Power, which in complexity is somewhere between a Ticket to Ride and an Age of Steam.

To sum it up: Railways of the Lost Atlas is an excellent package. It’s one of those games where if you for some reason have to slim down your collection to just 10 games, you will be happy to have this be one of them. The map building and minor company powers give it a lot of replayability, the adjustable map size and reduced number of cycles open the genre up for players that are not already familiar with 18xx. It looks great on the table and the depth of decisions will give you enough to crunch on for years. It won’t make you suddenly love aggressive stock trading and if you’re not in the mood for a knife fight, you should probably play something else. But for anyone even remotely interested in diving into 18xx, this is almost a must buy. I wish there would be more games coming out that are as perfectly executed and thought out as Railways of the Lost Atlas.

Hello,

As somebody who has been greatly enjoying discovering your writing, is there a newsletter I can sign up for to get email updates when a new post is made? Our tastes are aligned and I enjoy how you think about games. Cheers.

Thanks so much Jason. There isn’t, but I was thinking the other day of setting up a free Patreon tier to serve that purpose. What do you think?

I’d be a day-oner 🙂

Here you go: patreon.com/TalkingShelfSpace