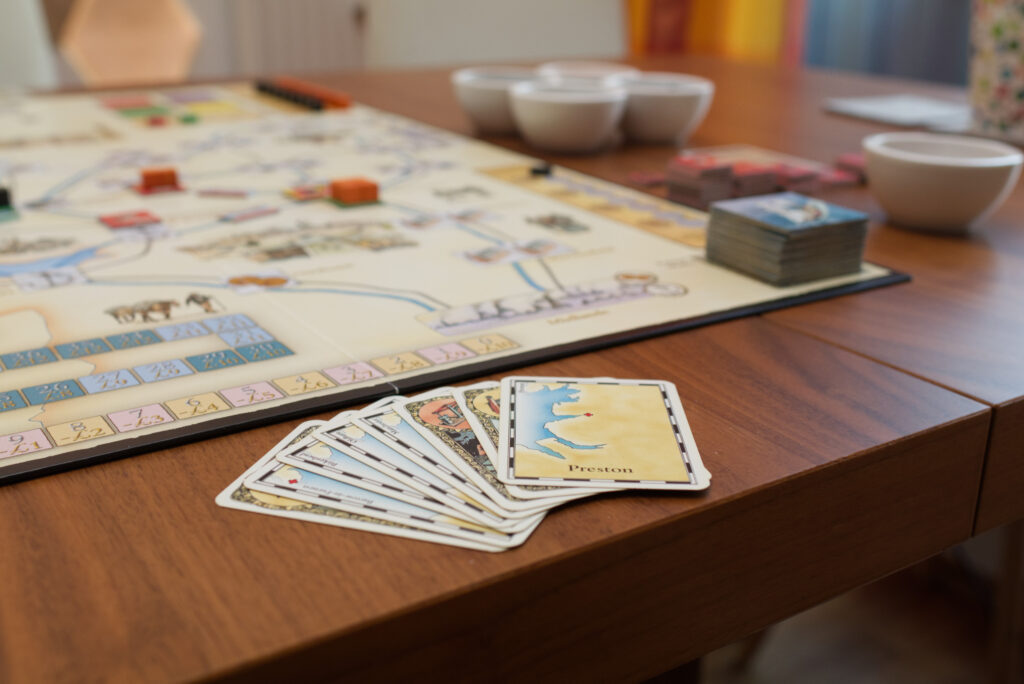

The story of Brass from it’s original version to – in the form of Brass Birmingham – becoming the number one board game on BoardGameGeek is a fascinating one for multiple aspects: how did a game from 2007, a time where the hobby looked much different than today, manage to stay relevant for so long? What makes this seemingly dry economic game so special that it has become an integral part of board game culture? And why do we have the twins of Brass Lancashire and Brass Birmingham?

The best part of setting out to tell the story of Brass is that it gave me an opportunity to meet design legend Martin Wallace, a man not only known for his huge number of influential game designs (Brass, Anno 1800, A Study in Emerald, A Few Acres of Snow, Steam, Princes of the Renaissance, …) but also for being one of the very few that managed to do the impossible: become a professional full-time game designer at a time when successful games still only sold in the hundreds or low thousands and the concept of crowd funding or YouTube influencers was still far away.

I met up with Martin at SPIEL Essen 2023 and we talked about topics such as his initial inspiration for Brass, his relationship with his designs, the infamous virtual link, the renaissance of Brass when Roxley Games picked it up, and his upcoming project Steam Power which combines elements of Brass and Age of Steam. In a sense, it felt like being able to talk to the creator of chess: some things may be lost to the fog of history, but what is there already tells an incredible story that even its creator couldn’t have imagined when he set out to just create a purely economic game. Enjoy!

Inspiration

Brass is such an amazing game, both if you see it from a design standpoint but also how it has become this cultural thing in the board game industry. I was wondering where it all started. Did you wake up one day and think okay, I’m creating the number one board game in the world? Or what was the initial thing that triggered you to create Brass?

[jokingly] Yes, of course, obviously I knew that people really, really wanted a really boring game about the industrial revolution in Birmingham, that’s gonna sell! That’s gonna wiz off the shelves. No to be honest, the inspiration for the game came from one of my regular play-testers going back to – I don’t know – 2005/2006, something like that. I’s a long time ago. Back then I was self-publishing games as Warfrog, one game a year. I had fallen into this routine where the games were kind of like there’s a war-game element to it. There was Struggle of Empires, Perikles, Byzantium, and they all involve conflict. I remember one of my play-testers saying “why don’t you take a break from that and do something that’s just pure economic?”, and I was like “okay, right, let’s try to do just an economic game”.

So then my other thinking is – because I studied history for my degree – there was a French historian called Marc Bloch, and he was a medieval historian during the Second World War. He said it is very important that historians focus on where they come from because those are the things you know best. So if you are a French historian, study French history. Don’t study Indian history or American history. It’s about focusing on the local. So I said okay, let’s apply this principle to game design: I’m a game designer, I live in Manchester, let’s do a game set in Manchester, around here. What’s Manchester most famous for? The industrial revolution. It’s also something I studied when I was at university and the history is all around you. The old mills are still there, the canals are still there. So it’s kind of designing about what you know.

That’s where the initial inspiration came from. I had this idea: you know how you do these economic exercises at school where it’s like we produce this to ship it to there because they need it here and then they produce something and ship it to there? So you have this general idea of things moving around, things being converted into other things. That was the basic underlying idea. We are gonna have our basic commodities which is basically coal and iron and then they are going to be consumed to create other things, obviously cotton and ships and so on. It’s creating this economic dance. This thing needs that thing, so we need to get that from there to there, and that then converts to this. And that was really from where it came from.

I actually don’t remember much about designing the game. I remember the play-testing took a long time because you had to balance the economy. You had to make sure one thing wasn’t too strong or too weak. And that took a long, long time.

How long was it? Months? Years?

No, months. I had to work quick because I had to do a game a year. So where some game designers will take years doing stuff, I do actually develop quite quickly. But it was a lot of play-testing.

You had to earn a living, right?

Yes, I had a day job. I was still a teacher then, so yeah, you got limited time.

Did you have to do research and read books or was it so much in your nature and in the surroundings you were in that you didn’t need to?

I still did a lot of reading. But there was a lot of stuff that I already knew and some things are just functional: getting maps of the local canal network and the train network. It was reasonably historical accurate. And yeah, there was just stuff that I knew. I know that in Liverpool there are ports because Liverpool is a port city, there is not a lot of research needed there. I knew from experience where the cotton mills were because these are places where I’ve been to. I’d go up to places like Preston or Burnley and places like this. I knew these places because I traveled through them.

So not as much research really, not as much book research as I would do for other games because I didn’t really need to do that.

Design Process

And how did you start drawing the map? As a non-designer, I’m always fascinated: you are sitting in from of a blank page, you have an idea in mind, maybe an idea for a mechanism, and then you have to start draw a map, right?

I suppose it’s a little bit like being an author in that your first book is probably your hardest one. Because very often – you find this also with aspiring game designers – the hardest thing is not starting, it’s ending it. [Alex laughs] The start is easy, it’s like then how do you damn well end it? But I had already developed this process. I used Corel Draw as a basic graphics package because you could do simple shapes. When I’m starting a map like that the first thing I normally do is like “right, I need a basic outline of the area I’m talking about” and then I need to be able to fit these cities in. I need to make sure there is enough space between them so that the counters will fit. These were all things I had to deal with before. So it’s not something that I consciously think about, it’s kind of on automatic. I can create a map for a game very quickly. I mean literally I can do the map in a day. Once I got the ideas in my head, it all comes out really quickly.

Do you take a historical map and say alright, from here to here has to be a canal because it’s on the map?

Yes.

I’m wondering how that works out during play-testing. Do you then tweak it and remove this canal and put it there?

It can happen I suppose. The thing is with the canals, you want to make sure you have the canals that were actually built but you can also say – because you are replaying history – well are there places where they potentially built canals. [Alex laughs] So you are twisting history a little bit but you do want the real canal network to be a potential outcome. I do like to create train games that have a degree of historical veracity, that they are rooted in the real world. That’s very important to me.

How are you approaching a game design? Do you want the players to think about X or have a certain feeling?

Yes, this is a very important thing in game design, thinking very clearly how do you want the players to feel? What kind of decisions are you presenting to them? So with Brass, what you are trying to do is it’s a business game. You got this much money, what are you going to invest it in? What buildings are you going to build? And where are the gaps in the market? Obviously with Brass it’s one of those games where if nobody is producing iron, you want to go to iron, as is the case in real life. If there is a gap in the market, that is where you go. You don’t want to go and compete where there is already lots of people producing a certain resource. So yeah, it’s very important that you think through how you want players to feel in the game.

Even if you narrow a game to this era in time and this locality, there are still many aspects you can put in there. You can put the exploitation of workers in or not, and this and that. Was it for you just an abstract thing, working on this economic level?

Yeah, it’s entirely abstract. It would be very difficult to bring into the game the conditions of the working class. Yes, I’m aware of it because I read Engles and I already knew this. But adding that would have been too much, so this is just purely an abstract economic game. You don’t care about the workers, they are not an issue in the game. Doing that would have created another game.

It might also mimic the perspective of the industrialists, right? They didn’t care about the people so why should it be in the game?

Yes, because you are working from the point of view of the mill owner rather than the mill worker. And yes there was obviously some industrial strive. Did it change the outcome of the industrial revolution? It’s like: not really. There were strikes, but eventually the rich guys got to where they wanted to be.

The more I was reading the things you said in past interviews, the more I was thinking Martin Wallace must be the most quotable game designer in the hobby. There were two things that stood out for me: “You don’t have to be a story teller because history provides lots of stories”, I really liked that one.

I don’t remember that, that must be from a long time ago.

[jokingly] Yeah, I’m thorough in my research.

The other one I really liked was “if you are adding rules, you are going the wrong direction”. The more I thought about this, the more I was wondering: you have this rich texture of history and you did such a reduction. There are only two resources you can trade with, there’s only so many industries. How much did you reduce [during development] and how much was it already reduced from the beginning? What was the first prototype like?

It’s a long time ago and I don’t really remember that much. I don’t think there was a massive amount removed from the game because you already learn not to put too much in. There are certain rules that you follow: you limit the number of different types of resources you have, you are aware of what thing … if I am doing a talk to aspiring game designers, I always say: the art of game design is learning what not to do. So you should already know what paths not to go down. There are certain things you just don’t do. You don’t always know what to do, but you should know what things don’t work. If you know what doesn’t work, you don’t waste time by going down that path.

Now because I’ve been doing this for a long time, really my strength as a game designer is I already know all the things that don’t work. So I don’t waste my time by even trying them. And then it’s kind of: after we have eliminated all the things that aren’t gonna work, what are the options left to us in terms of what could work?

It sounds a bit like in aeroplane design. They always say the plane isn’t done when you have put everything in you needed but when you have removed everything that’s not needed.

Yes!

Less things that can break. And it sounds like your design sensibility is in that direction.

Well that’s it. Going back to why you should be removing rules rather than adding them: every rule you add is a rule you can forget. You are setting people up to fail. Having said that, Brass is not a simple game and it does have quirky rules which were kind of forced on me by the geography of the game. Hence you have this really kind of odd rule about the connection between Liverpool and Birkenhead, and I wouldn’t actively choose to put a rule like that in.

But the problem I was faced with is these places are right next door to each other and there was a lot of ferry traffic between the two. Hence the famous song Ferry Across the Mersey by Gerry and the Pacemakers. But at the same time there were also train connections to Birkenhead as well and it’s trying to come up with rules that allow that situation to develop. In a sense, that for me would be a negative because those rules are exceptional.

To a degree, in Brass Birmingham – where a lot of the work was done by Roxley – there are fewer exceptions because you don’t have these geographical oddities to deal with.

Was the motivation behind that the historical accuracy or was there a game situation in the play-testing where you noticed you had to add that connection?

I think it’s more I needed a way for the Birkenhead [from] real life to also be presented within the game. To be honest, it’s a long time since I played Brass Lancashire and I really honestly cannot remember totally the reasons behind the rules. But [jokingly] I know that they are there for a reason, and it’s a good reason. I just can’t remember the reason. [Alex laughs]

The Original Release

So at some point you had the balance down. You released the first version, I guess in Essen?

Yes, I think it was 2007. It was originally called Brass and it only became called Brass Lancashire to distinguish it from Brass Birmingham. I think we released it in 2007 at Essen as we used to do because that was the place you could go, you got the games printed just before Essen and then you could sell a whole load of them here, get the money back so you could pay the print bill.

Aaah. [Alex realises the implications of intentionally pushing print dates dangerously close to Essen in order to avoid having to take a loan and instead basically have the sales before the bill arrives].

So that’s the thing you see. [jokingly] Because game designers don’t make a lot of money.

[jokingly] I heard

It’s hard. It’s hard to make money in this industry.

Especially at that time, right? Print runs were like: if you sold a thousand copies that was an enormous hit.

The thing is you had to do a minimum print run of 3000, because otherwise the print cost went up massively. Nowadays because you’ve got new print technology, it’s doable to do lower print runs because you have digital printing. We didn’t have that back then. Setting up a four colour printer is time consuming. This is why you want to run as many copies as possible. You set the printer up, that’s the expansive bit, and then you let the machine run. So the more you do, the cheaper it is per unit. Short print runs, very expansive.

It must be a huge finance gamble, right?

Yep.

It seems to be a theme that comes through in every conversation I have. I talked to Ryan Laukat about Sleeping Gods: he had this massive hit and everybody was yelling why haven’t you produced more? And basically it comes down to: if he would have done it and the game would have been a failure, he would have been [in huge financial trouble]. Were you in a similar situation with Brass?

Back then, all I aimed to do was one print run. So that’s what we did. We did one print run and because at that point I had a good relationship with Eagle Gryphon I think they did a further print run. But they paid for that, so I didn’t have that risk. But that’s another story.

But yeah, getting the print run wrong will kill you. So yes, I fully get it. You know these people say “oh, why didn’t you print more” but the reason is you don’t know whether a game is going to be successful or not. You really don’t know. You can look at a game and think this is amazing and print ten thousand and then find out people don’t agree with you. And then yes, you lose your house.

Even so if a game is critically acclaimed. Brass went up in the BGG charts pretty quickly. I think I saw that within a year it was in the Top 20 which is amazing. But that doesn’t necessarily mean a huge financial windfall, right?

Yes, because it’s just …the people who rate things on BoardGameGeek are the hardcore gamers. And the thing with a game like that is: once you got the game, you don’t say “it’s a great game, I go out and buy another ten copies”. [Alex laughs] No, you already got the game.

The thing that transformed the fate of Brass is the fact that the hobby changed. When I started, the hobby was very small. For this kind of game, the hobby was 3000 people, maybe 5000. You aimed to sell 3000 units and if you sold 3000 units, you were happy because that was the size of the hobby. Since then – due to god knows what, Kickstarter or whatever – the hobby is massive! I’m amazed. The fact that this game where we were lucky to sell 3000 has now sold – I lose track – a hundred thousand? I don’t know what the latest number is, but it sold in the hundreds of thousands. That is UNBELIEVABLE, and unpredictable. Nobody back then would have predicted that. It is just … crazy.

Enter Roxley Games & Kickstarter

I read a bit about the in-between times before Roxley picked Brass up. It felt to me like Brass seemed to be in a slumber. You had the success initially and I was astounded that not more copies were sold. Then Roxley came in and suddenly it skyrocketed. Did you always see that potential?

I have to be careful because there are legal issues here. Certain things I have agreed not to talk about in detail for legal reasons, but basically I fell out with Eagle Gryphon over another issue and we went from co-operating to not talking and there were lawyers involved. There was legal action, not over Brass but another game.

I completely forgot about Brass. I moved on to other things. Again, my mindset up until then was you do a game, you sell 3000, you move on. That was the reality, that was the world then. So why think about an old game, you know? I’ve sold the 3000 and moved on.

In the background, Brass was growing in its popularity and I wasn’t really aware of it because I was focused on the next thing. And it’s like “oh, okay, so Brass?” I think because Brass got into the top 10 at one point – it was like number 8 I think – and I thought “okay, that’s unusual”. And that’s kind of around the time when Roxley reached out to me. Gavan said “this is my favourite game, I would love to reprint this game”.

And really I should have said no [Alex laughs] because I never had heard of them. “Roxley who?” They had only done one game up to then, Supermind or so [corr.: Super Motherload]. They had done one game. They are a small company from Canada, why the hell am I dealing with this company with Brass? But for reasons I can’t go into in detail, I said yes. Best decision I ever made in my life.

It also matches what you said in the beginning. The hobby and the whole model has changed so much. From their perspective, it must also have been a crazy gamble, not only release one Brass but two at the same time, try Kickstarter, probably huge investment in new graphics. Do you have a feeling why they did this? Was it just a passion project or …

Passion! And that’s what I think made it work because it was around that time that I was in discussions to sell the design to Fantasy Flight Games because they were interested in it, only as acquiring its IP. Fantasy Flight – now Asmodee – there’s a lot of my IP that belongs to Asmodee but they are not using it, they are not re-printing games. So it’s just sitting there in a vault, it adds to their overall bottom line, it counts on their balance sheets but it’s not making any money. If I would have sold Brass to Fantasy Flight, that’s probably where it would have ended up because they didn’t understand the game where with Roxley, they were passionate about it and they put a lot of time and effort into the game to get it right.

The new thing that changed the world then is Kickstarter in that through Kickstarter, small companies could do amazing things. This wasn’t there back when I started, back in 1994 or so. And yeah, it was the right decision because they did a brilliant job on it.

In hindsight, the more one thinks of it, the more incredible it is. I checked the numbers: virtually everyone who backed it backed both versions, and this is years and years before Alexander Pfister did three versions of Great Western Trail. How did it come to that we now have these twins of games? Why didn’t Roxley just say “let’s do an updated version” or “let’s drop the old Brass and just do the new one”? Was it input from you to say “lets please also re-issue the old one”?

No, they originally came to me to ask about Brass Lancashire and then I mentioned that I had worked on Brass Birmingham. And I got it so far, but I was like: I’m not doing anything with this because of doing other things. So Brass Birmingham just sat there gathering dust.

So when I mentioned “oh, I got this second version” it was “oh, yes, we’re interested in that”. [Alex laughs] And then they looked at that and went “yeah, this needs work”. Because the version I had done was quite rough. As I said, they did an awful lot of development work on Brass Birmingham and changed the way certain things worked. They changed how beer worked, they smooth out some of the issues of Brass Lancashire where you’re now having the scout cards, and stuff like that.

But yeah, the idea of releasing both at the same time, that totally came from them, that was no input from me there whatsoever. They just decided that’s the way to go and it was a good decision.

And who would have thought it, right?

It’s also keeping the fans happy. There is people that prefer Lancashire over Birmingham, you know. So [jokingly] you can choose, nobody is holding a gun to your head and says you must have THIS version of the game. You can have either, you can choose which you want to play.

Iterating on the System

How is it for you to have someone else work with your system? You did Age of Industry before, you played with the base system. Is it like marrying off a daughter: this is working, do your own thing?

See you don’t know. The nature of the business is you design a game and if you license it to somebody, you hand it over and they may or may not do development work. You have to trust the people doing the development to be good at it. Some game companies aren’t actually very good at doing development work where others are very good. My experience over the years has been mixed. You only know after the event, and yes, by definition, they did very good development work on it because the game was very successful.

So moving forward I have total confidence in Roxley to produce a quality product. There are other companies – I’m not naming any – it’s like well, yeah, I’m not gonna put stuff with you because I don’t like the way you develop things. But generally I try to trust the company. Ultimately they are putting their money on the line, they are the ones putting effort in. I like to trust them to do what they think is right. I try not to be a possessive game designer because there are some game designers that say “no, you are not changing the game, this is my baby, leave it alone”. I try not to be like that.

It probably helps how you got started in the hobby, right? You can’t be precious about a single one. It’s more like I’m hitting so many balls, some of them will be home runs.

Yeah.

I found it fascinating that you tried to simplify Brass into Via Nebula. Were there many publishers that came to you and said “oh, we heard Brass is so successful, create us a new one”?

No. [laughs] Via Nebula came about because I was at New Zealand at the time and there was a guy there that was also designing games. We get together playtest each other’s games, and he tried to create this game where there are these interacting elements of the game where people are feeding of other people’s things. It really didn’t work that well in my opinion. But that set me thinking: well Brass does that. Brass is about feeding off other people. Somebody does something and you can feed of that, you can use there stuff to do your stuff. It’s all about everybody taking things from everybody else.

And so that set me thinking what about a really simple version. So I did this kind of fantasy train game. I remember you had the idea of places where you get the resources from when they run out you flip it, you got to move things around. So in the first version of Via Nebula, you actually had track, I think I called it donkey something. I think the original one was about the idea of donkeys moving stone, donkey stone or something like that, I can’t even remember the name of it now.

For some reason, I showed it to Space Cowboys and they really liked the idea. Now they did do development on it, they got rid of the track thing, you had this general pathway thing which I thought at the time was a good idea. They did a brilliant job on the artwork. But what’s interesting is: the game didn’t do that well.

Yeah, I was also surprised.

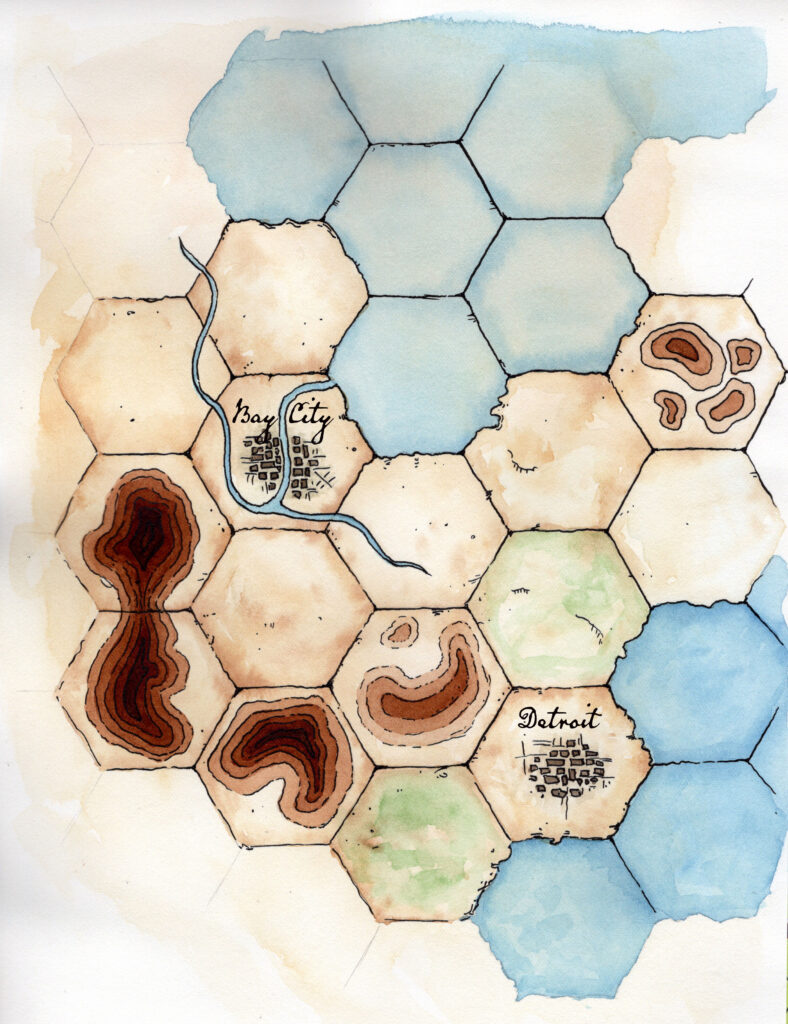

Onwards to Steam Power

I just come from a meeting with Space Cowboys where I was showing them a game that I’m putting on GameFound next year called Steam Power which basically is Via Nebula but done closer to the original version. So it’s a train game, you are building track as you do in Age of Steam. It’s kind of a mix-mash-up of Age of Steam and Brass. It’s gone back to building tracks. You have factories that produce goods as they do in Brass and when the goods all go, the person that owns the factory will get victory points. It’s not quite the same as getting income, but you still have that thing of people using other people’s resources.

Now in this game you are using them to fulfil contracts. You have these contract tiles that say you need two black resources and a white resource and you have to get these from factories on the board. They can be your own which are free or you can take them from somebody else. But if you take them from somebody else you have to pay them. So that’s kind of an additional thing where in Brass you don’t. The reward is in when you flip it. But in this it’s like if I take a white resource from your factory, I got to pay you a dollar. If I move it along a link you created with your train network, I have to pay you a dollar. So things have a price and if you run out of money, it really limits your options.

This new version, it works really well! I’m really super pleased with the game. It’s got that element of deciding where you want to build track, making sure you can access the right resources to get your contracts [fulfilled]. But also if you can play a contract, they give you a bonus action. Some of the contracts are like if you play this contract, it will give you some money, some victory points, but you also get to build more track. Another one allows you to build a factory, another allows you to draw more contracts. So what you are trying to do is set yourself up so you can do the things you want to do anyway but do them via the contract tiles rather than just building track or just building a factory.

So that’s going to be on GameFound mid January hopefully.

In what stage is it currently? Are you completely done?

A lot of the artwork is done. It’s gonna have little toy trains. [Martin pulls some train minis out that are test-components they – to my understanding – used to figure out the level of detail they can do in a production version. They look pretty astonishing].

This is the other inspiration from Brass: I love the [Iron Clays] in Brass. I thought: wouldn’t it be cool if you had poker-chip-style track rather than the kind of cardboard tracks? So the idea is it’s going to be that clay composite from Brass but those are going to be your track tiles and then you are going to have fake silk maps, so you gonna have cloth maps you play on. So this is showing you the final artwork style. [Martin pulls out a beautifully illustrated map printed on cloth].

It’s got a nice 19th century feel to it. Physically, it’s going to be a nice game to play because the pieces look nice and feel nice. At the same time, the gameplay is simpler than Brass and Age of Steam. This game, I played it multiple times with five players and it took 60 minutes. It’s quick playing. And it scales. The game length is determined by how many contract tiles you play … you have these contract tiles [Martin shows some thick hex-tiles] which tell the resources you need to get. You set the board up randomly. As you can see, you’ve got the [city locations] marked there, but randomly set the board up with city tiles. So the board is never the same. And not all of the city tiles come out, so it’s sometimes like “oh there’s going to be a shortage of orange, I need to make sure I get into those orange cities before they run out”.

So the game is never the same, there is always a new problem: You look at the board and say “right, where is the best place to start, where can I quickly access all four resource types?”. You want to be able to access resources so you can start playing contract tiles because that’s how you win the game. The contract tiles give you the most victory points.

You sound really excited and proud!

This game is awesome! If this game doesn’t win Spiel des Jahres, I will be disappointed. [Alex laughs] This is what I’m angling for [Martin hands Alex the cloth map; it feels fine woven and good quality, completely different than for example the coarsely woven map in Pax Pamir: Second Edition]

Oh wow, looks lovely!

So this will be the deluxe version. Hopefully, if we meet all our targets, we will have five maps in it. The nice thing about having these light-weight silk maps is you can get a lot of them in a box. because they fold up so well. [Martin shows the cloth bag he had the components stored in] This is the travel bag for Bloodstones. Because there is no cardboard in the game, you can just put it in a bag [Martin starts dropping and banging the bag onto the table, fake-acting like someone on an infomercial, it’s funny as heck] and it doesn’t matter what you do to it. You can bash it around and you CAN’T – HURT – THIS – GAME. It’s indestructible.

[Alex jokes] It’s like the antithesis to the giant Kickstarter box with minis.

Yeah! The rules are simple but you still got interesting decisions. Do I build my track out this way or where do I build a factory, what order shall I try play my contract tiles in? You have interesting decisions to make but you don’t have that massive rules overhead that you have with some other economic games where there is pages on pages on pages of really detailed rules and it’s hard to do anything.

How many pages of rules is this?

I don’t know, it’s probably twelve. But I deliberately try to keep the actions simple. If you want to build track, you just build track. You don’t pay anything for it, you don’t need any resources. You can build up to two track tiles in an action. Just put the track down, boom, that’s the action, done. Because I figured why put barriers in the way of people doing things. It’s like take the barriers away, just let them do the action.

What’s the bottleneck players have to be careful about? Is it the money to spend …

Yes, if you’re taking goods to much from other players, you’re gonna run out of money and it’s very difficult to have access to everything yourself. Normally, you have to feed of other players. So you want to make sure you got money for those, certainly towards the end of the game when resources are becoming scares. Certain resources might be a long way from you and all the stuff close to you has run out. The resources are limited.

When you build a factory, you put five resources of that colour on the factory. When those resources go, you flip the tile and the player that owns the factory gets victory points at the end of the game. So that’s kind of like the Brass bit, not super Brass-like. But those resources are now gone. Now I still need black cubes but they are further away and it’s someone else’s factory and I don’t have any train track going there. Suddenly you are going to say “wow, one of these cubes is going to cost me 5 dollars, and that’s a lot of money!”.

There is a LOT to think about in the game but at the same time it’s super quick to play.

[jokingly] You make me think about stealing that bag.

You can’t! Because [a big publisher] wants to play it so I have to give it to them on Sunday. But there’s a page already up on BoardGameGeek. The rules are already up, so you can look at the rules and hopefully get a good idea. There is also a Tabletop Simulator version of the game you can go and play.

Taking a Different Approach

I know I’m known for complex games. I’ve reached the age now where I don’t want to do complicated games just for the hell of it. I think there are too many overly complex games out there. I want to do games where – again going back to using the minimum set of rules to produce the maximum amount of fun, the maximum amount of interesting decisions. Choosing simple rules that then lead to complex situations. I’m trying to not make life hard for people. Don’t confuse them, don’t give them rules that are hard to remember. Just keep it simple.

I think that’s why I appreciate your design sensibility. Currently I’m playing games like Voidfall, 40 pages of rules and extra booklets. I played Mr. President, the GMT game, it takes like two hours to set up. I felt like a librarian, having to reference stuff here and there. So 12 pages of rules actually sounds exciting to me! [Alex laughs|

Don’t quote me on it! But there aren’t a lot of rules. And basically the rules are similar to the action you do: you want to build track, lay two pieces of track down, boom, that’s a rule. Play a contract tile, all you need is: can you get all those resources onto your network because your network has to be contiguous. Build a factory, put a factory down, put the cubes down, doesn’t even have to be on your network. It only has to be connected to track of some type. So most of the time you are building track or playing a contract tile or building a factory. Sometimes you grab more contract tiles but you rather do that with a contract that allows you to do that because it otherwise is a bit of a waste of actions.

So the range of actions is quite limited but you have this reading of the map at the start of the game. Where is the bottleneck, where are the shortages going to be? Getting to places before other people get there, trying to block people off. Or how many factories do you build? You might decide someone else is connected to a city somewhere, they have to pay you for these resources. It’s good!

Either I will get a tremendous headache or lots of fun out of it! I’m excited to see.

I’ve played it with a lot of different people and you don’t have to be an experienced gamer. It’s the kind of game you can play with a less experienced gamer. Also – as you can see from the artwork – I want it to be pretty. I feel a lot of these train games, they are [jokingly] “designed by man for man, women shall not play these games because it’s a man’s activity”. As we know in the hobby now, there are a lot of women in the hobby and I wanted to do something that feels more attractive, more appealing to the female half of the hobby so that they are not put off by the rather austere straight lines and things. Why not make it visually attractive?

It doesn’t necessarily have to be females. I have never played an 18xx game [in part also] because most of the graphics shock me.

Yes. They are not visually pleasant. They work functionally.

And especially if you want to do crowdfunding, it’s so important that a game looks inviting.

Yes. But it’s also: like the guy doing the artwork you just saw there, that was not done digitally. You know how all artwork now is done digitally? That was all done on paper, all done by hand with watercolours! Actually there is a picture up on the website because that’s they way Leith works. And I really love that. Doing things the old school way. If you do it digitally, you have to design a digital program to make mistakes because the nature of proper hand drawn stuff is there are mistakes, that’s what gives them their charm. The lines are not quite straight, there are little gaps. When you do the watercolours, sometimes you go over the line. That’s what gives these images charm because there are human errors in there. Where if you ask a computer to do something, it will do it perfectly. So then you have to program it to do it less than perfectly. But even then you can sort of tell that it’s being done by computer.

And again this a very important thing to me because I’m going back into publishing: I’m using local talent. I’m not going on the internet and grabbing somebody from the other side of the world. Leith he lives in New South Wales, I’m in Queensland. But all people I’m using are people that live close enough so we can get together. So what happened in the beginning of the year, is like right, we’re gonna get all the people together in this project and we rented a house for the weekend by the beach, gorgeous . We all went away for the weekend and said right, we all are gonna play these games so you understand the game. So rather than me just saying I need this art, it’s like “this is the game, play the game, understand the game”.

A bit of “do your thing”?

I like the idea of “let creatives be creative” rather than me guiding and say this is the general direction but if you’ve got a good idea, go at it. And then you feel more invested in the project. Rather than feeling like work for hire, they feel part of a team. And they are! It’s great, they all chatter to each other on discord, I don’t even get involved! They just do stuff without me knowing it and it’s great, I love it, because they feel part of a team. That for me is really important, that face to face time so people know what they are doing.

This concludes the interview. Many thanks to Martin Wallace for taking the time to sit down with me. You can find all information about his latest projects such as Fighting Fantasy Adventures and Steam Power on his website https://www.wallacedesigns.com.au.

After our conversation, I reached out to Gavan Brown of Roxley Games as I realised how interesting it would be to add his and Matt Tolman’s perspective of working on Brass Birmingham as well. At the time of writing, I haven’t heard back but I’d love it if at some point in the future we could turn that conversation into the part 2 of this piece.

If you enjoyed reading this, please leave a feedback in the comments. Doing in-depth interviews like these takes a lot of prep & research and it’s really rewarding to see that so many of you seem to enjoy reading them. Showing your support helps getting future interview partners on board! You can find more interviews like these in the interview section.

Thanks Alex. I really appreciate this interview and the previous ones. I believe that reading the designers’ view of their work is very interesting.

That was a great interview. It gave good insight to the designer and showed a lot about why his games generally are the way they are. An enjoyable read, and I hope you found all the research and prep work worth it, because the product was very much appreciated.