Welcome back to part 2 of my conversation with Vangelis about Hegemony. If you haven’t read part 1 already, you should do so here. In this part, we talk about the economic aspects of the game, playtesting, running a Kickstarter, and what the future holds for Hegemony but also Hegemonic Project Games. Enjoy!

The Economy

Let’s quickly go to the economic part: there also is this whole economic system in the game. How challenging was it to come up with something that is simple but interacts that well with the other elements? The end result is rather elegant: you have company cards with a price, they require a defined number of workers, trained and not trained, and you just have three salary levels. There is a lot of game packed into those rather simple mechanisms.

If you would ask me what the most difficult thing to come up with in the beginning of the game was, it was this: how would companies and workers work out?

We knew we had the concept of the capitalist owning companies and workers coming in to work in those companies and getting paid. So yes, we would have a labor market that would change how much they were paid. We’d have taxation that would affect how much taxes are, and so on. But practically, how do you translate this? How do you show the companies and the workers coming to work?

We did try a lot of things! At some point, we had large cards that would represent each whole industry. So the working class could put many workers on it and the more they would put on it, the higher the production would be and so on. At another point, we had it more abstracted like tracks: this is a production for this industry and this and that. It would look like a giant spreadsheet [both laugh], it was intimidating.

So we had to find the right way to implement it so the rest of the policies would work. We had the policies in the back of our mind so whatever we’d choose, we knew that it would be changed from time to time depending on the policies. But you had workers coming in and you should have three different numbers based on the current policies.

At the same time you had to consider how many workers are going to that industry because the more workers, the more they have to be paid and the more they will be producing. And then you would have machinery that would increase the production but not the salaries. And then you have skilled workers and unskilled workers, how much does production change? How much do the wages change between skilled and unskilled?

It was a nightmare to try to take everything into consideration. I remember us trying and trying and working on it for a few weeks at least before finally coming up with the solution we ended up with. First of all, the whole thing about skilled and unskilled workers and if they are going to be paid differently and if they are going to be producing differently, we removed this from the players so they don’t have to take it into consideration. They don’t have to do calculations on their own.

You have cards that are separate companies, they have a fixed number of workers in it, a fixed combination, with a fixed production and only three wages which correspond to the total workforce. This way you immediately remove a lot of calculations that the player needs to do. The player will just see okay, this will produce five resources, great, and I need one green worker and two grey workers, perfect. So I don’t need to consider the scenario if there is only one worker there how much will he produce and how much will he get paid, no. It’s either all or nothing, in small increments, and this way we can make it work with everything else that we later want to add in the game.

So we did that and machinery is just a token that increases the production, it doesn’t affect anything else. That was the first thing that we tried and that made sense, it worked. Then we started build everything else around it. Okay, so we have these company cards, you have different industries, you start the game with a few … or do you? I think we played games where you didn’t have any companies in the beginning, we added them afterwards. How many? Do you start with one, do you start with two? Four? These all come up through various playtests.

Another thing that was challenging was the fact that we had a lot of different amounts of money. The working class at times would count pennies, it would count “I have 15 money, 16 money, 18 …”. And the capitalist would say “ have 400, 500, …”. The scale was different in the amount of money each class would use. So we had to work and bring them closer together. Thematically someone could say okay, the working class has vastly different amounts of money compared to the capitalists. One has millions and billions and the other has a hundred, tens of hundreds dollars or euros. The reasoning behind it was always you don’t look at a single worker, you look at the working class as a whole. So when you take into consideration that the population is much higher and you have less money but more people, their amount of money can be closer to what the capitalist will have. Still the capitalist will have more but you try to minimise the difference between them in order for the game to make sense.

In the end, we ended up going with six different denominations, you have single coins, one Vardis, and it can go up to 100 Vardis in the coins that players have. We needed to show this vast difference of how much money you end up making in the game depending on who you play.

And within the companies, are there hidden rules or formulas you used? Like if you design a company that needs one white worker, two grey workers, it produces X and the price will be Y? Or how do you calculate all this?

Behind every game, there is always a giant spreadsheet somewhere in a computer. [both laugh] Hegemony is not an exception to that. When we first made the companies, we had it in our mind that okay, you have each skilled worker produces this amount and an unskilled worker produces that, this is how much we pay an unskilled worker, this much we pay a skilled worker. So depending on the configuration of each company, that would tell me the production and the wages at the bottom.

We started with that and initially the numbers were like “so this one gets payed 17 money” and “this one gets 23”. At some point we realised it’s too much, the calculations needed to be toned down a bit. We made everything multiples of five to make it easier to calculate and we also made some adjustments in the productions depending on gameplay and how things seemed to work. So while we ended up doing a few adjustments, there is still a formula behind all the numbers.

Also the export cards for example: You have good prices, bad prices, but this is calculated variance. You don’t have random numbers on the cards. If you take all the cards and spread them out, you will see that you have the same number of low values and same number of high values, they are just spread out.

Usually in such heavy games, there are a lot of behind the scenes things that the designers have made that the players don’t see or they do take for granted. But there are many cases of countless hours of calculations, spread sheets, and everything to make sure the values are right, the players will only see the final values. They play with them and the fact that they have fun means the work that was put in there was good work, it made sense. But it’s not apparent that so much work has been put [in determining] the costs. This applies to every game, not just Hegemony.

[jokingly] I imagine a lot of playtesters had to suffer wrong prices until finally you got something that is fun.

One of my favourite designers is Mark Rosewater, he is the head designer of Magic the Gathering. He usually says: we play a lot of bad games of Magic so that you can play good ones [Alex laughs]. This applies to all games. During playtests, you play a lot of bad games. You try a lot of things that don’t work so that you can make sure that the final game comes out and it works for players and it plays out well.

Yeah, I noticed that in conversations with friends. They were like “oh you get to play this prototype, that must be so exciting” and I was “no, it’s more like work because often they are not fun yet”.

Yes, exactly! [smiles]

Import & Export

To wrap up the economy part: there are two elements of Hegemony I still don’t have a good feel for, so you are perfect to help me. It’s the business deals and the export market. In your mind, considering everything in Hegemony, was the idea always that the capitalist class would primarily sell to the other classes and is the export market more a backup solution if everything goes wrong? Or what’s the role of the export market?

So, initially, what we had in our minds was for the capitalist to produce and then sell to the other players. But it quickly became apparent that the other players wouldn’t buy enough to make it viable for the capitalist. And there were also cases where the working class would say “I’m not buying anything” for whatever reason, “I don’t want to give you money”. Even in the final product, you still have games where players will play like this and say “no, I don’t want to buy anything from the capitalist”.

So we had this problem and one way would be to enforce the working class to buy things but then you have less of a game. Like how many things can you enforce the player to do? Where are their decisions coming in? We already did that with food where we said “okay, you need to buy food at the end of every round, you need to spend this amount if you want it or not” but it didn’t make a lot of sense to force the players to buy other things from the capitalist all the time. There was a lot of potential there for either side to break things, to play in such a way that it would be very unfun for the other players.

Let’s say that the working class had to buy everything from the capitalist. Okay, so the capitalist raises all their prices very high because they can. Okay, then alright, lets limit how much they can raise the prices. Okay, but then you start putting in limitations. What do you allow them to do then?

So selling to the foreign market was always going to be part of the game because it is something that happens. We realised that in the game the capitalist ends up selling more there than to the working class, at least in some games. Is it bad, do we want to leave it there? And we said let’s leave it there, let’s leave it like that. Let’s leave it up to the players because it does allow for better gameplay at that point. It is something that the capitalist class when forming their strategy can count on. They can count on the export card being there and sell their stuff there. The prices may not be the same, they vary from round to round, but you also get cards that allow you to manipulate this market a little bit. But it is something that we can count on.

As the game moved forward, at some point we knew that at least one of the capitalist actions in each round is going to be selling to the foreign market. We decided we’re fine with that, it makes sense thematically. You do have to sell to the foreign market. We would have preferred it if there were more sells to the other players, but as I said, enforcing that would have led to other problems. So we decided to leave the extend to which that will happen to the players.

And why is it that the capitalist player cannot sell arbitrary amounts but you have this rule that every good has these two amounts one can sell. Was it just to make it more challenging?

No, it was to simplify the math behind it [chuckles]. Initially in our first games, we had cards that had the value for each good. Like food, okay, it’s 7 each, or 6, or ten. So you would decide to sell 6 of those, and 7 of those, and 5 of that and you actually needed a calculator to do everything [both laugh]. So the capitalist would play, the others would play, the capitalist’s turn would come up again and they were just finishing up doing all the calculations. Imagine: 6 times 7 is 42 and then 8 times 3, so plus 24, …

… carry over the one …

Yes, something like that [laughs]. It was too much. I think we actually changed this after we started development. The main design had been finished, Anastasios Grigoriadis (the developer) came in and started playing with us and working on the game. One of the first things he said was like “guys, you have gotten used to it, but this needs to change” [laughs]. And we decided to explore a few other options but in the end the one that worked best was to have fixed groups of things you would sell with the amounts rounded up to five. It made the math simpler, so now you can do it without a calculator [laughs].

This actually changed from the way we were playing it where you would sell everything you have. Now you had to sell fixed amounts and there would also be a case where you had like three of one resource but you had to sell at least four. We realised okay, this is not bad, this makes it even more interesting. [To have to] make sure that you have the necessary resources, that you keep some for the next round, and so on. It worked much better the way we ended up doing it.

So the simple answer is: math. We wanted the players to do less math than they already did [laughs|.

Yeah, thank you for that! [laughs]

Playtesting and Balancing

You mentioned before – and I heard that in my conversations with other authors – that as soon as you have an economy, you have this huge challenge of balancing everything and playtesting again and again. How do you as a designer approach it? I have to imagine you use some techniques so you can play on your own and balance it a bit on your own before you go to play testing groups?

As I said before, behind every game, usually you have a spread sheet. At least the way I work –and I know some others as well, not everyone does this – we try to assign values to the resources and the various actions you do in the game to take on some values and then when you prepare cards, depending on what the card does, it’s easy to fill in the numbers because there is a formula behind whatever you do. Obviously playtesting may change things because you may have assigned a value to that action but players will want to do that action less or more, and this changes the value. But especially when there is an economy with resources, when you assign values to its resource, then it’s easier to balance things out because you say I give that many resources because that matches. So each action I’m spending that much my reward is that much. […]

In another game of mine, I remember we had this situation where everything was assigned values and at the end there was a column that was the power level of the card. We were saying we want the cards to be like between 2.5 and 3.5. So you hash out like this is a 2.8, this is a 3.1. It’s good to have some variance and not all to be exactly the same, but there to be a range between which you want the cards to be. So if it was too high, if the card was very powerful, you needed to change something. If it was too low, likewise, you had to change it’s numbers. Usually this is how we approach an economy. It doesn’t work in all games, some games you have to experience them empirically but usually there is at least a number assigned at the back of the the designer’s mind to everything you see in the game.

And from all the playtesting, was there any particular thing positive or negative that you still remember. Any important things you only found out during playtesting?

[Vangelis thinks for a moment] From the top of my head, I can’t remember anything. For example in the game we are designing right now, every playtest is like “lets try this, we playtest, okay, this worked, this didn’t work”. This happens in all the games. In every playtest you realise something works or doesn’t work. So I can’t pinpoint to something exactly because it’s such a natural part of the process of playing, okay, this card was too expansive, this needs to be lowered.

Especially in Hegemony, you don’t have that type of cards. You don’t have cards where each one has a cost on it. For example, in Freedom! which is also a card-driven game of mine, each card has a number of action points at the top. You had cards valued with 2, 3, or 4 which was the number of action points the card would give you. For the cards with 4 action points, the effect was more powerful than the cards with two action points on them. So there you had to balance the cards, okay, is it a two, is it a three, is it a four, where do I put it?

In Hegemony we took a different approach. We didn’t have action points. In Freedom!, even your basic actions had a cost in action points. So this costs one action point, this costs 3, and so on. Depending on the card you discarded, you could do some of the basic actions or you couldn’t. In Hegemony, all the basic actions have the same cost, which is [discarding] a single card. So we didn’t have a number assigned to each card, it’s power level or something. The only case where we have numbers are the transactions of the export cards and the business deals. These are the once where the values were based on some formulas, like food ranges from that price to that price, I have that many cards with low price, that many cards with a high price. I try to mix them up, not put all the expansive values on the same card, not all the low values on the same card, and so on.

So you just make sure you do this spread of the values on the cards and usually it works. I remember some of the event cards we needed to tweak a little bit. I think we went to Kickstarter and for the event deck we were still unsure on a few cards. After the Kickstarter, when we spend more time developing the game, I set there with a spread sheet and tweaked some values a little more. We had that with legitimacy: how much legitimacy should each even give depending on how much you spend?

You also provided this Tabletopia version for potential backers to play. Was it just an incentive for people to try it out or did you also generate data from it that helped you? For example Carnegie, they said all the data helped then to re-balance the departments in the game because they had so many plays of it.

The thing is that when we started working on Hegemony, it was January of 2020. Guess what happened on March of 2020? [laughs] The pandemic came, so Varnavas had to go back to Cyprus and we had to do all our work remotely. So right from the start, we needed a way to test the game remotely and by chance I used Tabletopia. I hadn’t used Table Top Simulator yet. So we started with Tabletopia, and each new iteration and each new version we would test it there.

And as we were getting closer to the Kickstarter, [we thought] we have it here on TableTopia, why not let backers play so we get feedback? It’s such a complicated game, it has a theme that is unique, and it is also a game that promises something that is very … ambitious. I think even Rahdo in his preview mentioned that it was very ambitious what this game claims it does. We wanted the players to play it because it would give us additional feedback. If we were going to the Kickstarter and everybody playing the game was like “oh, come on man, I don’t like it at all. What is this?” we would have taken it into consideration. Or players commenting on [various aspects].

So we wanted it there and in hindsight, it was one of the best decisions we made regarding the Kickstarter because a lot of people were hesitant [about] the Kickstarter. They liked the theme but Hegemonic Project Games was a new company and they didn’t know what to expect. They had been burned out of many Kickstarters, so they were very hesitant. Our response was “try it, go play it yourself. It may be for you, it may not, up to you. But you can see the whole game there.” And we literally had the whole game there. Not the solo part, that was developed afterwards, but you could test everything.

We got a lot of feedback on the game from those playtesters. We didn’t get game data as in this card should cost more or less, but we did get feedback on the things players liked or did not like. And we got feedback that the game was good, that players really liked the game which was very positive for us. It boosted our confidence and it looked like we had done something good here. But it also allowed us to say the players are for example complaining about too many rounds, it takes too long. Can we do something about it? And we actually did change the number of rounds in the game between the Kickstarter and the final release. This also needed its own playtesting because it affected a lot of things in the game and so on.

In addition, we got the chance to meet a few of the people who were very vocal in the forums on BoardGameGeek and they actually became our playtesters prior to the game’s release. We saw there were some guys that played the game a lot, they liked it a lot, they played it many times. Great! Guys, we are thinking of doing theses changes, do you want to test them? Do you want to help us out? We found some very, very helpful people through that process. And they indeed helped us a lot to bring the game to its final form and make sure everything worked. It was super, super useful to have a playable version online while the Kickstarter was running. It was super important.

You’re right! For a first time company, it gives people the confidence of yeah, there is an actual game there. Maybe they mess up in the production, but we know the game is good.

Exactly, you know what to expect. It’s not a blind purchase anymore. Like go on, try it, we have the rulebook online, read it, all of it. It’s not a promise, there is a game. [laughs]

Tell me a bit about how it is to have a Kickstarter. I’ve never designed or published a game, I can only see the numbers and 600,000€, that sounds like a lot of money. Is it like a lot of work and excitement before the Kickstarter, then you toast with Champaign and say okay we made it, and then you live in fear because you have to work a lot to deliver on the promise?

Let’s say it’s an experience having a Kickstarter. [laughs] It has its good and bad sides. Obviously, it’s very exciting to see the response of something you made, how people react to it. You may make a game and people are like “oh, this is awesome!”, the numbers flying high and everything. On the other hand you may see very small growth, you see comments like “hey, why is this like that?”. Or you may hear absolute silence, that is even worse. [laughs]

So Kickstarter is a very good indication of how your game is going to be perceived afterwards. Of course [running] a Kickstarter is a whole different animal. You may have a very good game but in order for it to go well on Kickstarter, you have to do a lot of work for the Kickstarter itself. There is a lot of preparation involved. Many, many months in advance, you need to start getting [email addresses] from people, gather followers. You need a critical mass before you launch a campaign. You also need to make sure that what people see in the campaign is appealing, that they like it, they find value in what you offer. That value may be a new theme, gorgeous artwork, the miniatures that you are getting. Whatever it is, you need to make sure the people find value in what you are offering. It may be a very low price compared to what it will be afterwards, and so on.

You have many different approaches you could take on a Kickstarter. Many different things to consider, from pledge-levels to shipping to add-ons. If your game goes well, you have additional problems coming up with stretch goals. [laughs] I remember Ignacy Trzewiczek from Portal Games. When he ran the Kickstarter for Prêt-à-Porter, he made a post that said he had designed three small modules as stretch goals […] and he was like I’m done, I’ve designed everything I can about this game. [both laugh] And then the Kickstarter came and was going super [well] and he was like okay, I need to come up with new stuff. On the spot, new ideas started coming in and he created new stretch goals. This mirrors the experience I had with many of my Kickstarters, even from my earlier days. With Among the Stars, the first version of the game was not on Kickstarter, it was on [Indiegogo]. But then we went with Kickstarter for the re-print and it went really well and we had to come up with new stretch goals: okay, lets give this, and okay, what else do we need? We do that! And while the campaign was going, we would come up with new things, we would test them and then show them.

So with a Kickstarter, you have this period before the campaign, where you have to prepare, do your calculations right, make sure okay this is the price I’m going to [sell the game for], this is how much I’m going to charge the backers, theses are the pledge levels, these are the add-ons we will be having, and planning for stretch goals if things go well. You are of course in communication with the manufacturer to see the exact cost of everything, how much can you spend. When are the numbers okay? Okay, I have that many backers, which means I can [get a lower price], so this allows me to put some more stretch goals out, and so on. So there is a lot of work beforehand. Also the graphics, how the campaign it is going to look, 3D renderings, all that stuff.

Then, while the campaign is running, it’s another whole different animal as well. You have to be there for the questions of the backers, like constantly monitor where are we now, you are going to need another stretch goal, what do we put there? Okay, so the guys in the comments are commenting a lot about this, do we reply, what will we reply? You have to give updates.

And then after the campaign finishes, there is a big sigh of relief, like “aaaah its over!” [both laugh] You’re happy, yes, there is some pain, but then … then you need to live up to the promises you made. So you need to start working to create everything that you promised but is not ready yet. You also need to make sure that everything you showed is actually produced the way you showed it. And you now have a product in your hands, not just a game. You have the actual product, you have things like what’s the size of the box, what’s the insert going to be like, what’s this, what’s that? There are a lot of things that need to be taken into consideration like shipping arrangements with boats: when is this boat leaving? When is the manufacturing finishing? There are many, many things for a publisher to consider after the Kickstarter. Usually there are a million things that can go wrong, unexpected things that may happen. And that’s why delays in Kickstarter are the norm and not the exception. Because no matter how much you prepare, how [many additional months you plan in] as a leeway. Like I expect to be finished in 6 months, I will make guarantee in the campaign the game will be delivered in 8 months. And then you end up delivering in 12 or 14 months because yeah, things happen [laughs] that change everything. So this is what comes after the Kickstarter.

But it’s still a great tool for publishers. Obviously it’s a huge benefit money-wise. It allows you to produce the game, to manufacture it at a level that everybody is going to be happy, both you and the backers. With upgraded components and miniatures or whatever you add in your game. But at the same time it is a burden that you need to be careful of. It’s not the magical solution to everything. It has it’s own difficulties and things you need to take care of and of course you always have – depending on how many things go wrong – you always have the communication with the backers which needs to be constant. Sometimes things go wrong and you would prefer there wouldn’t be anybody out there that you have to tell about it, you just take care of it and move forward with some delay. But now we have backers and need to be transparent with them. You need to tell them hey guys, this and that happened, okay, these are what we are doing to fix it, this is what we’re working on now., what the new timetable looks like, and so on. But in the end it’s part of the process for many companies right now. It helps promote the game, it helps get exposure for the game. So we have to live with it and try to make the best out of each Kickstarter.

Hegemony was a hugely successful Kickstarter. You two as designers and the company itself are now on the radar of many players. The production is really lovely, there is lots good content in there, artwork looks great, etc. There is the reputation part, but of course there is also the financial part. Can you speak a bit towards that? I would imagine producing Hegemony would cost quite a lot of money with all the stuff that’s in there. Is it then that the money you collected in the Kickstarter basically pays for the production and maybe pays for your rent? Or were you planning with Hegemony coming to retail and that’s where you make money? Is the Kickstarter alone already enough that it payed for all your work?

It’s kind of both actually. So Kickstarter obviously covers the manufacturing costs. Even before the Kickstarter, you do an analysis what your game costs to manufacture at certain quantities. Depending on how well the Kickstarter goes, you’re looking at producing within a range.

Now the Kickstarter went better than we had expected. We had some numbers in our mind but you never know how it goes. It may go way lower than that, it may go above that. It went above what we were expecting which allowed us to add things to the game, to upgrade it. For example the boards initially were not dual-layered, we made them dual-layered because the number of backers allowed us to do that. Or the silk printing of the meeples. Initially the meeples were going to be normal. There are companies that [always] know that they will be doing this [but] they have it as a stretch goal for the players. For Hegemony, it was an actual stretch goal! We were going to print the game without silk printed meeples and without the dual layer boards.

The fact that we got that many backers allowed us to upgrade the game and as a result we also increased the game’s MSRP. For the backers the price remained the same but we upgraded the game a lot, so we [had to] increase the MSRP of the game to incorporate those changes [in the retail edition]. But the game turned out better than we had initially [imagined] and it was due to Kickstarter and to the success that it generated.

Now as for the financial part, Hegemonic Project Games started as a start-up and so it had some initial funding with which it did all the work before the Kickstarter. The artwork and some other things. But then the funding from Kickstarter itself was what helped cover the expenses of the production and then setup the company for the coming period where the game was produced, hit the market, and we also got revenue from the copies sold in distribution. This is where we currently are at. So right now it’s a normal publishing company which has some income from the game it sells and also a lot of expanses [laughs], wages and stuff. We are [jokingly] a middle-class company in Hegemony as game publisher. [laughs] Something like that. And we currently are working on our next game and we hope that history will repeat itself with the new game as well.

Things to Come

I was just browsing my notes and there would still be so many elements one could talk about in Hegemony, but we would be here for another two hours. So let’s look into the future: in the booklet that’s part of the Kickstarter production, you mentioned that you were experimenting with adding the financial market but left it out. So in general, I would ask you the question: where do you see Hegemony going and where do you see the company going? Do you think there will be expansions for Hegemony at some point?

We have actually discussed this in the company and in the future we would like to revisit it and perhaps make an expansion. We don’t have something currently in the works, like right now. We have some ideas and a few things discussed we could add to the game. And we see that a lot of people are asking for one online. They really like the game and would like to see more content for it. So this is definitely on our radar for the future.

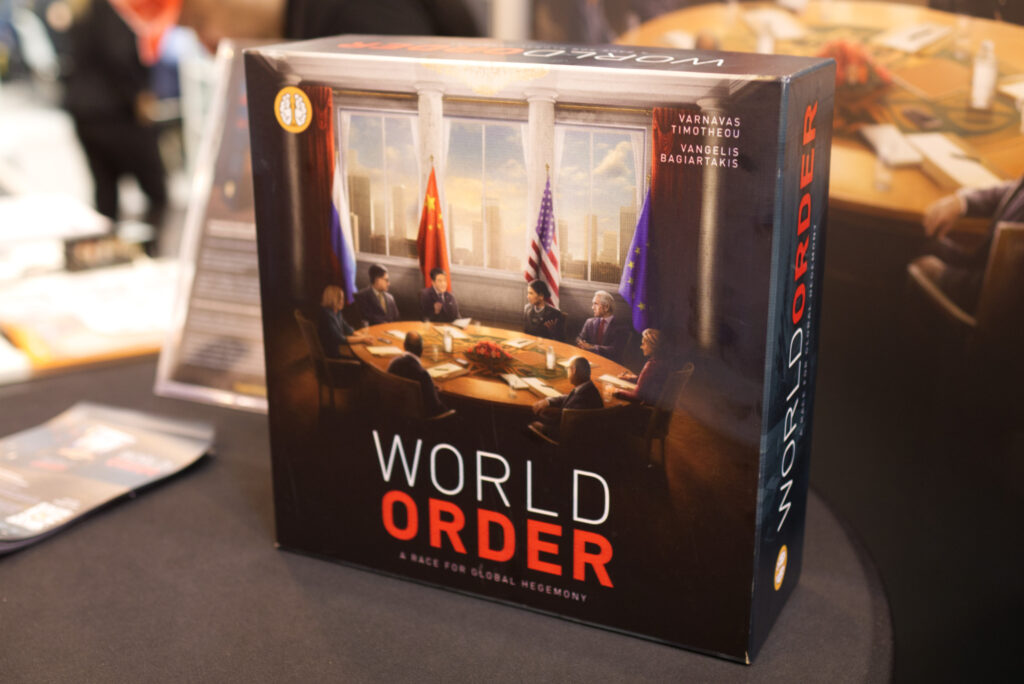

Now as for Hegemonic Project Games, it still has the same vision: it wants to make games that will help people learn about serious topics: politics, economy, international relations, and so on. Our next game will be “World Order”, which we announced in Essen and is about internal relations. Players will be taking on the roles of global super powers like the USA, China, Russia and the European Union and they try to spread their influence around the world. This game takes a look at politics at an international level, like how each country spreads its influence around the world, what are its goals, what is it trying to achieve?

I will definitely link the short conversation we had about it at Essen, people really liked to read all the info there. Is there anything new you can already reveal? Like how is it going with the game? What state is it? What are the challenges you are currently working on?

We were actually surprised by the reception World Order had in Essen, people were very happy about it. Everybody was expecting us to do it to the level of Hegemony and we were a bit cautious because we were thinking of making this game perhaps a bit simpler than Hegemony so it’s more approachable. But people would come up to us and say “is it going to be like Hegemony?” [Alex laughs] People wanted it to be more than what we perhaps initially had envisioned. We took that feedback when we returned and we actually did some changes to the game to increase a bit the asymmetry, to increase some elements in the game. The game was [already] thematic but we realised we needed to bring it closer to Hegemony than what we initially had in mind.

Still it’s not going to be as complicated as Hegemony, nor as asymmetric. But you do get a different feel and you do play differently depending on the country you play. For example, when you play China, you are focusing way more on economic actions like foreign investments and production of consumable goods, that sort of thing. When you play the European Union, you are more into diplomacy, diplomatic ties with other countries, Russia is very good on production of energy and raw materials and there is a military aspect as well that is more prominent compared to China or the European Union. And you have the US which can build bases all around the world, it’s very strong both in military and diplomacy.

So depending on who you play, you do play differently and you do have to take into consideration the strength and weaknesses of your country. We found a few ways to make the version that we were working on when we went to Essen even more thematic and make some of your choices and some of the things you do in the game a little bit more interesting and fun to play with.

The main thing we do is that we combine deck-building with area control, which I don’t think is a space that has been explored much in game design. We had deck-building and worker placement recently with some very, very good games. So we are combing deck-building with area control and we are kind of working on making sure that it is fun and engaging and thematic as much as Hegemony is.

Are you still aiming for like a two hour playtime? Or has the feedback lead to you increase it a bit?

It has increased a bit because we did some changes that increased the length of the game. It’s not going to be as much as Hegemony [laughs] but it’s somewhere like 2 1/2 hours. 2 1/2 to 3 hours, this is where I think we are going to end up with.

Nice, because aside all the praises Hegemony got, I think the one critique most people have is that it’s more like an event game, they don’t get it to the table as much as they would love to.

Yeah, a quick filler! [laughs]

Probably good for you to aim for the shorter playtime.

Unless we make Hegemony the dice game where you play five minutes or so. [both laugh]

Anything for you personally? Do you hope to be working full-time for Hegemonic Project or do you have any other games you are working on?

Actually, I’ve been working now for full-time for Hegemonic Project Games for more than a year. I’m Head of Design and Development in the company now, so all the projects that we are considering I’m working with them. On some I’m the designer, on some other projects I’ll be doing development. The focus of the company remains to create games that provide something to the people, like have some educational value behind them. We would like to have a booklet like Concepts [the booklet from Hegemony] with all our games in the future. So for World Order, there will be a booklet with the academic theory behind international relations focused on what each country wants, how it tries to achieve this with real life examples in it and everything. It will have a high educational value as well. So that’s our goal.

For all the projects that we are considering down the road, this is always the main axis around [which] we are moving: however we are going to present this, we need to make sure that people learn things out of it. Learn how things work in this field so they get a lot of value, not only gameplay value but also educational one.

From everything I hear, it sounds like it won’t be only two games but you are hoping and planning for many, many more games to come from you?

Yeah, we have a few things down the road. [chuckles]

This concludes the interview. Many thanks again to Vangelis for being this generous with his time and answering all my questions. This was a fun one! I hope you the reader enjoy our conversation as much as I have. For more info on what Hegemonic Project Games are working on including World Order, checkout their website and blog.

If you enjoyed reading this, please leave a feedback in the comments. Doing in-depth interviews like these takes a lot of prep & research and it’s really rewarding to see that so many of you seem to enjoy reading them. Showing your support helps getting future interview partners on board! You can find more interviews like these in the interview section.