One of my most unique gaming experiences of 2023 was without a doubt Hegemony: Lead Your Class to Victory, designed by Vangelis Bagiartakis and Varnavas Timotheou. It’s a thriller woven out of heavily interconnected political and economical concepts that pits up to four players against each other, each trying to get their unique, asymmetric faction to win while being part of the same fictitious nation. Every policy bill proposed, every company build, every worker employed puts ripples throughout the fabric of gameplay mechanisms that all players will have to deal with. Hegemony is such an ambitious design, it leaves players incredulous that it works at all, let alone to the level of perfection it does. It has the unique distinction of there existing competing threads on BoardGameGeek declaring each single faction as the one that is overpowered and can’t be beat.

I had the unexpected pleasure of getting to know Vangelis during my visit of SPIEL Essen 2023 where we ended up having an impromptu interview about Hegemonic Project Games’ upcoming game World Order. It was so much fun that I later reached out to Vangelis and asked if he would be up for having a longer conversation about Hegemony. We ended up talking for almost two hours and could probably have continued for a couple more, there’s so much to talk about in this game.

I’ve again split the interview into two parts for better readability. This is part 1 where we talk about how Varnavas convinced Vangelis that they should work together on this idea of his to create a game that actually will teach people about politics and economics in a fun way, how their collaboration worked, using a card-driven mechanism to convey theme, the political aspects of Hegemony, and more. Enjoy!

How It All Started

I’d like to start at the beginning: From my understanding, you were already a full-time developer when you and Varnavas first met. You had done successful games like Fields of Green and Kitchen Rush. Varnavas had this idea of creating a game that teaches people about politics and the economy but he realised he wasn’t a game designer, which was very smart. Most people make the mistake of just creating a game themselves and overestimating their abilities as a designer. Instead, he went to this board game design contest where you were and he chatted you up. Tell me a bit more what that situation was like. Was he just another guy chatting you up and and you get pitched ideas all the time?

[Vangelis laughs] Every year, we have this board game design contest in Greece. Varnavas saw this contest and he had this idea in his head. He tried to design something himself and he joined the contest, he submitted the form and everything. He was trying to build it on his own and as part of the contest, they were doing some events for participants to test their games with the audience, like in a big hotel with tables all around. You could sit down and people would come over to just play the game. As part of that, there would also be some talks with advice from more experienced designers to support newer ones. I was giving one of those talks on that day and Varnavas had come for this event. After I had finished, he introduced himself and he told me what his plan was.

He thought that this was a very interesting topic and he would like to make a game that would help you learn about politics and economics and important stuff that is all around us, but that we sometimes don’t pay that much attention to or we don’t understand it fully. He wanted to do that through a board game. So he had decided to create a company, to launch a startup and publish this game. But he knew his limitations, he knew he wasn’t as much experienced in board game design. He was looking for advice, he was trying to find people and work with them.

He had heard about me, so he approached me and we discussed it. I found the idea very interesting. I found the theme – as most people did – very intriguing, something different. It was challenging, so I was immediately interested in it. I told him yeah, I would love to work on that. We left it at that – this was around summer of 2019. So that’s how the whole thing began.

We then met again near the autumn and we had some calls. He was also trying to find the team. He was looking into artists, he was looking into a developer. Varnavas had done his research! He was a first time publisher, but he knew that it’s not enough to just have a designer, you also need to have a developer to look into it afterwards. Right from the start, he wanted to do everything right.

So it wasn’t a quick cash grab or “okay, I have this idea, let’s do it and be done with it”. No, he wanted to put in the time necessary for it and make sure everything was as it should be. He even came to Essen that year in October 2019 where he had a very simple booth where you basically just signed up to be notified about the game. He had a giant banner behind him that said: “Are you interested in politics? Would you like a boardgame around politics?”. There were people that would come and start having discussions with him. So it was the first step in interacting with board gamers: finding out what people expect to see in the game, what it should have in it. Are there board gamers interested in politics first of all? That was the most important question.

It was very illuminating and it was a very fun experience for him as well. Around November/December, he finalised the deal to work on this together. In January of 2020, we started working, in the beginning with some calls then he decided to come here for a few weeks and flew over to Greece. We would meet every day and start working on the game. That’s how everything started.

Maybe let’s go back a step. You’re a full-time developer, I imagine you must be thinking: okay, I have to feed my kids, my time is valuable, this is another guy with an “idea”. What did he pitch you? Did he pitch “I will build my own company and I will hire you” or “this is a project, let’s do a Kickstarter”?

At that moment in time, I was a freelancer. So I would take on projects from various companies and that’s how we approached it. He told me that he would create a board game publishing company. I think Kickstarter was on the table right from the start. I don’t think he would have gone completely on his own.

But yeah, the plan was that I would be commissioned for this project and we’d work together. We explored various financial options like royalties or full payment in advance, there were some discussions about that. The idea was that I would be payed to work on this with him. He had all the know-how on the topic and the theme and what the message of the game would be. I had the experience in game design. Both of us were necessary for this to proceed. So that’s how we approached it in the beginning.

Regarding whether I have many guys coming over and asking me [laughs]: usually in events like that one, you do have people saying “hi” like “okay I’m working on a game, would you like to see it?”. So I do get this from time to time. But the truth is that Varnavas stood out compared to the other people that usually come to me because most of them are on a hobby basis. Like “okay, I’m doing this on my free time, any time you want, just have a look at it, give me some advice”, and so on. [Alex laughs]

Varnavas was focused! Like “I’m going to do this, I’m going to build a company, I’m going to start a business, so this is serious talk, not like a hobby thing, not something I’m doing in my spare time.” And what was clear even when discussing with him was his passion, his vision: he didn’t just want to make a board game! He wanted to make something that would help people. He had a purpose for the game and the company, a vision that came through in our talks. It was another thing I found interesting. Like yeah, this might end up being something good, something that is important.

I’m so interested in this because when I did my research for this conversation, I tried to google Hegemonic Project Games and I wasn’t sure whether it is this one guy with his hobby project and he has like super nice web designers, that’s why it looks so professional – or – is it multiple people trying to start a new company?

Now it makes way more sense the way you describe it and why you would even agree to do it. If I would be you, I would always be hesitant, like “yeah, yeah, it’s another guy with an idea and suuuuure, it will be the next big thing”. Him approaching it from this whole other angle and also setting up a booth at Essen first to do the market research, I have never heard that story before.

If you look up the picture [of the 2019 booth], it does have graphics that don’t have anything to do with Hegemony. That came a few years afterwards. So it was completely different graphics, it didn’t have anything to say about the game because there was no game yet. He had a concept in his mind, he knew what he wanted the game to convey, but there was no game yet. But he did it and he also got experience of what it meant to go to Essen, what other publishers do. It was very important and valuable feedback received by doing it that way.

I imagine it’s also interesting for you to work in this way. You don’t have to do as much research, you can just ask someone. Varnavas is very knowledge in this topic. You can just say “hey, I have this idea for a game mechanism, what do you think? Do I have a basis for it or not?”.

Exactly! And this is the best thing. I’ve also experienced it in “Freedom!”, another game I did which was also heavy, very thematic, and very rich in history. I probably couldn’t or wouldn’t do it on my own because I would have to do all that research, read like tens of books. While I would like to do it, I don’t have the time to do it.

So having someone who is fully knowledgeable in a topic and be able to ask him questions “why is this, why is that? Does this make sense?”, it’s super, super valuable and saves you tons of time when you are designing. My ideal scenario for every game I’m going to work on in the future is to have an expert on the game’s theme on my side, like to be able to ask them, to have them share insights on how things work, why they work this way, what’s the meaning behind some decisions. It’s super, super valuable.

Collaborating

Tell me a bit more about the interaction between you two. Was it like he’s always the research guy, the one that pitches the topics, and you are always the person who creates the game mechanisms? Or was it more like you read stuff that you wanted to have in the game and he was also presenting game mechanisms?

It’s a bit of both. In the beginning, I was the experienced guy. I would talk about mechanisms, he started by sharing some articles I could read and get into the mindset of the theme. Specifically it was the politics table, that’s how we started. He would explain the ideas and theories behind it. As he would talk, I would try to come up with mechanisms and I would show them to him: “We could do it like this or we could try a deck-building mechanism, or a worker placement” or “this sounds like it would benefit from if it was card-driven”. The more he would explain things, the more I would try to come up with something that would fit that theme well.

In the beginning it was mostly like that. But as we worked more and more together, he at times would provide very valuable feedback on mechanisms and also after a point he started suggesting things on his own because he really got into the mindset of a designer. He realised “okay, so yes, as you had said this won’t work but why don’t we do it this way?”. He would come up with counter-arguments to suggestions of mine that were perfectly valid counter-arguments and he would also come up with ideas which sometimes were very focused, and sometimes they needed refinement. But that was the great thing about brainstorming. This exchange of ideas, this ping-pong of thoughts where something the other guy says makes your brain go a different route and think things you wouldn’t consider on your own.

It actually amazed me how quickly he got into that mindset of a designer and how quickly he started to think on his own “this won’t work because it will create that problem, like we need to keep the player more engaged” or “this is too confusing for the player”. He would see things that in the beginning I would need to point out like “no, this won’t work for this and that reason”. After a while, he would realise this on his own, so the conversations would move forward more quickly and he would provide very valuable insight or ideas of his own.

For him, it must have been similar to how you described it for yourself as always wanting to have someone so knowledgeable in your next project. He suddenly had direct access to a seasoned game designer and that accelerated his own progress to become a good designer himself, right?

Yeah, exactly. He knew what he wanted to have featured inside the game but he wouldn’t always come up with the cool mechanism on his own or why something needs to be tweaked this way or not. As you said, it was also very useful for him to have somebody from the other side with that advice.

I always enjoy coming up with mechanisms around a certain theme. I’m a theme-first guy. I prefer working on a specific thing, trying to adapt it into mechanisms. So it always excites me to have someone describe a theme to me and then try to come up with a cool mechanism that will showcase that theme.

Let’s for a moment forget about the Hegemony we know now, the finished product and everything around it. When you two started your conversation, what was your initial idea for the game or the thoughts you wanted players to think about? Was there any key message you wanted to have in the game?

So right from the start, the key point of the game was that you have these policies and they can range from socialist to neoliberal. You have the various groups in society push for them in different ways and usually some benefit one group more than the other, but all these groups have reasons to want it to go their way. It is to their advantage and they will explain why it’s better for the whole society if it goes there. The other groups will tell you the exact opposite thing.

That battle of ideologies was always at the core of the game. Varnavas would be able to explain this much better than me. But he had this theory based on [Antonio] Gramsci on […] which class is the hegemon in a society. That was the basis that he wanted to be conveyed as well as the whole interaction between everything. You are not on your own. Each group in society is not on it’s own. It cannot succeed on its own without the existence of the others and how they interconnect. Somebody needs to build the companies in order for the workers to go there and work. So you need to have this – let’s say – “cooperation”. At the same time, the capitalist builds a company but they want what is best for them. Ideally they would like to not spend any money at all. The workers, they want better conditions. They want to take care of their families and everything. There is always this back and forth between the needs of each group.

We needed to take all of this into consideration inside the game and it was important for us to not show just a single point of view. We didn’t want to make this game be just about the capitalist and everybody else doesn’t matter. Nor did we want to make it like “oh the capitalists are all bad and we should show what’s wrong with capitalism”. No, we wanted to take a different approach, more from a distance, and not take sides, just base things on the academic theory and try to put that into the game without any agenda whatsoever.

We were constantly trying to avoid favouring one side over the other because we knew that people have very strong feelings about politics, obviously. We didn’t want people to feel offended or like we were portraying things in a way that was not right. So we wanted to focus on the academic side of things: this is as it is and how can we use this to help you understand how things work? Then you can make your own decisions whether your society works well or not and what needs to change in your society. We’re not trying to show that society works best if policies are like this or if they were like that. We just wanted to show what the effects of the different policies are. You will then decide what works best how and why.

I remember Varnavas telling me: “What you want is for people to have discussion on the table, to discuss about politics while playing the game”. I think [laughs] this is one thing we did achieve, to get people to have strong discussions on interesting topics while playing the game.

A Card-Driven Role Playing Game

Hegemony was a smashing success. When I did my research, I thought the key thing for this is that it looks like a Euro game but you actually created a role playing game! What I noticed is that whenever I teach Hegemony to new players, it takes no time at all and people actually start saying things like “we as the working class want this” or “of course the capitalist will do that”. Was this something that developed naturally or was it something you had in your mind, like “okay, these mechanism are there just to be able to play, but the players need to play their role”?

[With a joyful tone in his voice] It actually developed naturally and we were also surprised by that. Even in our playtests, whoever would take a role, they just started roleplaying. They would start spitting out quotes from famous politicians or famous capitalists’ or communists’ quotes, or whatever was more fitting for their role in the game and there was a lot of trash talking and fun bartering.

It came out naturally and at first we thought okay, these players are friends of ours who playtest the game, we know each other, it makes sense, we do it in other games [as well]. Then we would start showing it to other new playtesters who would see it for the first time or some other publishers who would consider it later in the process near the end. We would show it in a Zoom call for example, launch Tabletopia, try it there and we would experience the same thing from them as well: roleplaying. Everybody would start quoting politicians and behaving like they were indeed the head of that class. It was amazing! It was very fun to watch and as I said, it came out naturally. We didn’t specifically aim for this to happen. But we did aim for the theme to be there, making everything thematic and have everything make sense. It flowed out naturally. The consequence was always roleplaying to emerge.

And when you noticed it happening, did you change things to lean into it so players would do even more roleplaying?

Actually no. We just wanted to make sure everything was thematic in the game, even the names of the actions. Some of them are very straight forward like “buy food” or “build company”, you can’t be more straight forward than that. But for some other actions like “lobbying” that lets you take influence cubes, we chose names that would convey the actual thing behind the action to make it more … immersive. We wanted the game to be very thematic so that players would be immersed in the theme and everything would come out of that.

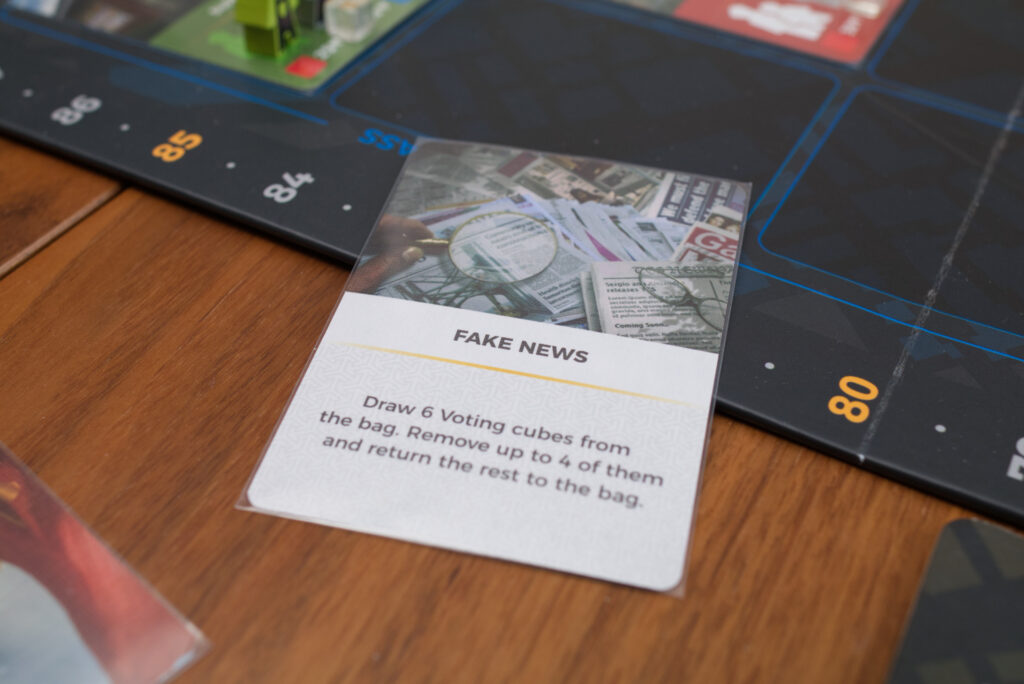

I think it’s mainly two things that makes Hegemony so role-playable: you picked archetypes that everybody knows as the classes, like everybody has an idea what a capitalist or a working class person would be like. The other thing is you used the card-based system. It’s basically like you gave players cue cards what they should enact, like “Fake News!”. Hints almost like “hey, this is part of your role, lean into it”. But in your design diary, I read it wasn’t always clear you would be using a card-based actions system, right?

In the beginning, we were still figuring out what game we were trying to make. So Varnavas liked the game to be simpler, to be appealing to a broader audience so someone not experienced in board games would still be able to play it. Very early on, we would explore many different options. At some point we discussed deck-building where one has different kinds of decks with different cards but they would interact with each other. So I would play company cards and somebody else would play worker cards to go to these companies.

We were trying to figure out what would work best but also what would fit the theme best and as you said, having cards that are very thematic helps convey the theme better. I hadn’t realised it before but as you said they are like cue cards, telling you how to act. Indeed, they guide you in a way.

The main reason we went with them was that they conveyed the theme very well that we wanted to convey. So it was very straight forward: you’d have artwork, you have a title indicating what you are doing, and then you have the card’s effect. But they would help you enter the world of the game and be immersed in the game. So that was the reason why we went with that.

Freedom! helped us do that because I had that experience. I had seen while working on a card-driven game [that it] helps convey the theme better and helps move the player’s actions forward. So early on, to be card-driven was a very strong contender for this game as well. But we did explore other options. In the end, it seemed like it would make the better fit so that’s why we went with that.

It’s a testament to how well it works that your cards don’t even have flavour text on them. I played some historic games lately – like Votes for Women – where every card had a nice flavour text and historical images on it. And I still couldn’t tell you the name of a single card. I just played them and at some point – as much as I liked the theme – forgot to read the flavour texts because the functions were mostly along the lines of place a cube here, place a cube there, do this. It got very generic.

From the top of my head, I can probably name you at least 20 cards in Hegemony because I remember someone using it, we laughed out loud, and someone went like “no, you can’t do that!”. I think you hit the jackpot by using the card-based system if you don’t even need flavour text to convey the theme.

I hadn’t even considered that. It’s true, we didn’t put flavour text on the cards. The title on its own was enough to to tell you everything you needed know about it because the mechanics would also re-enforce that title with what you would do, it would make sense with the title. It wasn’t just “Fake News” or “Unemployment” and just add a cube somewhere or move on a track. What you would end up doing, the effect of the card, was so much tied to the theme of the card that it would make it more memorable and more vivid in your mind.

How did you set out designing the decks? I imagine that was very challenging. Were there key political elements you wanted to put on cards and you later figured out the mechanisms – or – were there rather mechanisms you would think about and later you had to find a title?

I’m not entirely sure at this point how we went into this. But I think our first goal was to create the basic actions, the basic structure. Like [for the capitalist class], one of its basic actions is to build a company. For the working class, one of its basic actions would be to go there, to assign workers to a company. We knew that it would have to deal with getting health, getting education, so this eventually became “buy goods and services”.

So I think we first identified what the key actions of each player would be and then we started to create cards with variations of those basic actions. As the game was being made and started to get more into shape, we would perhaps think of other effects as well that we would try to put in the game. There were things we initially left out and then we would put them back in. Or things we added later in the game and we created one or more cards based on that.

The cards would change a lot up to the point the game went into print. There were changes in the cards, both big and small. But we first worked on the basic actions of each player and then build upon that. Usually we would come up with an effect first, like I want to change one vote and will also put cubes in the bag, okay so we make it policy-specific and we make a theme around that like “Taxed Enough Already”. That is a card that lets you change the taxation policy and it also adds a few cubes in the bag.

So we tried to find appropriate things and there were also some cases where we had the theme and we wanted to make a card around it because some phrases are very powerful like “Proletariats of The World, Unite!”, so we wanted to have this as a title. I think we had designed that card and then it was just to use the title. We liked the title very much and so when we changed the card a bit, we wanted the title to remain.

We had a lot of cases like that. Varnavas was always trying to find the best theme for each card. I would suggest something that in my mind made some sense so it could work, but Varnavas would be like “no, let’s try to find something even better, something even more fitting to what the card does”. So it was a little bit of both in this case.

And you as a designer, how do you see the deck? Is it like each faction has 10 key cards that are super powerful and the rest are filler-cards? What’s your analytical take on how the decks are constructed?

My ideal scenario would be for all 40 cards to be equally powerful, to be equally important. However, you need to design a few cards that are more situational because … first of all you can’t make all cards at exactly the same power level. You can try but usually you won’t. Especially for the cards that end up doing something very specific, there will be times when that specific effect will be super powerful and there will be times where it will be worthless. That’s the reason why you have the whole “discard a card to do a basic action” because you want to give players a choice, you don’t want to limit them to just what they have in their hand.

On the other hand, you want to have people be excited about the cards they draw and the effects to be interesting and fun. You want the players to want to do the effect of the card, it to be something they think will be very valuable to them, something to be excited doing it. At the same time, you need to make sure it’s balanced and doesn’t break the game.

Usually, we would start with a basic variation of an action and then we’d make it a bit more powerful but also more restrictive in a specific way. For example, you can buy goods and services at a lower price but you can only buy them from a single source like just from the state. Or you can propose a bill and get two cubes in the bag but it has to be for that specific policy. We would make the cards more specific and that would allow us to make them more powerful.

That’s giving the players the option of “do you want a generic effect?” (you can always discard the card to do the generic effect) or “do you want to do something more powerful” but it will have to be under these restrictions. So at the beginning of their round, the player sees the cards in their hand and they can decide: “which ones will help me do the things I want to achieve?”. So these ones I will definitely be playing for their effect and the other ones I’ll be using for basic actions effectively. So this is the key [situation] we wanted to put the player into, to have them decide which ones to play and which ones they are going to discard to pursue their strategy.

It’s interesting how you phrase it because I never thought about it in this way: if all the cards were equal, nobody would be excited about any one card. If there are some stronger and some weaker cards in there, people really get excited when they get the “good” card.

Yes. We did realise there were some cards that were better in the early game and some cards were better in the late game. But we said “it’s okay” because you can always discard them to do other things and you usually want to do other things. So of course it’s better if you get a card at a certain point. It’s super useful for you but also creates a very memorable moment playing that card and doing something powerful. If you get this card at another point, well, you can always discard it and do what you wanted to do, it’s okay. You can still win, you can still move the game forward, you can still pursue your own strategy. So this was basically our approach, this was how we looked at it.

We realised there ended up being some key cards in each deck, like we knew that some card is very useful for the working class or for the middle class “Migration” is very powerful. At some point near the end, we were discussing about one card. I think one card was removed and we were exploring which card we would put in its place. We used to have two “Migration” cards and it was argued with Varnavas: “why don’t we put a third migration, it’s so key to what the middle class wants to do, it’s very important for them”. So we did that, tried it and indeed it helped the player.

The same argument could be made for the capitalist. There are a few cards you really want to see at some point in the game. But I think having them in a deck where you draw from and you don’t draw the whole deck … that was on purpose to increase replayability and have the games not play the same. So you may not draw that card, still you should not depend on that specific card to win. If it comes, great, but you have other tools available. This card may not come up but you draw other cards that can help you. Maybe they were not part of the strategy you had in your mind but perhaps you can follow a different path now that you got those cards and they can really help you on that path. So you could try that. This creates different games and different experiences and that gives you an incentive to play again, try new things, and you don’t have each game play out the exact same way.

In one of our games, we afterwards had a post-game discussion and there was a bit of a controversy because one person said “oh, you got the Cooperative Farm early on, this is why you won”. Or “I got the Offshore Companies where the capitalist class is allowed to move money too early”. We were discussing: how much effect does the luck of the draw getting the powerful card at the right time really have? You’re probably the best person to ask: in all the games you’ve seen, how much does the timing of which card you draw when really matter?

I think it will start to matter maybe after you are very, very experienced with the game and all players are at the same level. But if you put an experienced player out with a new player, I think the experienced player will win nine out of ten, or ten out of ten games because the experienced player will know the effect of everything in the game. If something is interconnected, they know what to push, where to focus, where not to expend a lot of resources, and so on. So at some point, I will admit there is an element of luck, like this card is useful in the early game and this card is useful in late game, and I happened to draw them at the correct point. Like in round 1, I got the one that helps me early and in round 5 I got the one that helps me in the late game, yes, this may help you a little bit. But you still need to play well in order to win. So it’s not just the cards. I can very easily see a game where someone doesn’t draw any of those cards in the correct order but still gets to win because they managed to outplay and out-manoeuvre their opponents.

Especially with Hegemony, we realised early one – and it wasn’t on purpose but we did see it emerge at some point – how different the games would end up looking even if you changed a single thing. Like all else being equal, let’s say you start the game and on the first round you change policy number 7 (immigration). You change it to C where you have open borders, lots of new meeples come in every round. Imagine the same game, the same players, the same cards in their hands but you change this policy to 7A where you have closed borders and you have less meeples. The game will play out very, very differently all else being equal and the same can be said for healthcare, for taxation, for wages. If you change one policy and keep everything else the same, the game will end up looking very differently and take a very different route. Imagine now having seven policies that change over time.

So we realised very quickly we are having very different experiences as we were playing. We hadn’t changed much in the rules, like we were playtesting and adjusting things, but even with our changes the difference that we experienced while we were playing it was immense. I mean like different scenarios [would arise] and so one game was more tight, fewer money. Another game it was going much better for me, I had money, I had more options but at the same time something else was more difficult. It was super interesting to do that and it made us want to play the game and not get bored of it. We can still play a game of Hegemony and enjoy it even after having played it hundreds of times because we can’t tell from the beginning how the game will evolve, how it will turn out because everything is in constant flux. So that was another thing that we realised as we were playing: the cards do matter, but not as much as the players think they do.

The Politics

Let’s talk about the politics part. You said the politics table was there from the beginning. Was it always the same seven policies?

No, in the beginning it was something like eleven or twelve policies.

Oh wow!

[Vangelis laughs] It wasn’t in the form we have it now. Varnavas gave me a list very, very early on and it was around eleven or so policies. As I said, I wasn’t that deep into the theme yet. So we started discussing each of them: do we need that, okay, how much do we need it? This we can live without, this is super important, it has to stay in. To tell you the truth, I at this point don’t even remember which ones we left out, but I do remember there were more.

Also in the beginning, policies 4 & 5 (healthcare and education) were the same policy, so changing that policy would affect both those resources. At some point, it was Varnavas who suggested that perhaps we should break them out into two different policies. In real life, you have the government saying that “my welfare policy is this”. It would usually affect both things. But it made sense since we had different resources and different ways to get prosperity and it also would affect the taxation on the other players. It made sense to break them apart and we tried it and saw that it was much better to have them separate of each other.

So that was one case where we broke one into two others. But other than that, there were more policies in the beginning and we decided to just keep those that mattered the most. Even now with the finished game, one could argue that you could take out policy 7, instead have a fixed number of workers coming in every round and don’t deal with immigration. Yes, the game could still work. But this added an interesting element to the game, it made sense thematically, it is part of our everyday lives and people can relate to having open borders or closed borders in their country. There are always discussions happening about that [topic]. So it was an important aspect to have in the game. All the other ones are even more intertwined in the game like labour market or fiscal policy / taxation, so these had to be kept in. But there were a few we left out, I can’t remember which ones they were.

One of the most fascinating things I read about Hegemony is that you initially didn’t have this victory point reward for proposing and winning a policy change. You only later on added it because people didn’t realise how many consequences changing a policy has towards the rest of the game.

We had some games where people would not bother proposing bills. They would see that okay, this is what it is, health costs that much or you have to pay that much in wages. They were so much focused on their cards or some others things they wanted to do that they would not pay attention to the politics. Even now with the finished game, I’ve seen that in demo games for example in Essen.

We played with a fixed setup and so in each game people had the same cards in their hands, the same companies on the board. I would see games where a group would propose five bills in the first round and there was another group that wouldn’t propose a single bill or like just one. It was fascinating to see these different approaches.

Obviously we also experienced this in our own playtests and we realised that it’s good to give players incentives to change things because they may not realise [that they should do it] in the beginning. Or you want to award them for doing something that benefits their class because in the end that’s what VP stand for: are you doing things that benefit your class? Moving a policy to where it will benefit me is something good, something I should be rewarded for doing. So that’s why we gave points for that.

What I realised is that sometimes when you have a complicated game, players have too much information in the beginning so they don’t know what to do. Usually they would just look at the cards in their hand and do that. So you want to have an incentive to have them do something different than what a card mentions.

If we take the finished game and one would remove this victory point incentive, would the balancing of the rest of the game be still the same or is it that in the final version you have to propose policies because it’s such a vital source of victory points?

Basically it’s not that it is an important source of VP. What is more important is that you change the policies in your favour because if you don’t, it will be very hard to win.

Let’s play a game: I’m the capitalist and all the policies are in section A, like socialist policies. Or even they are all in section B. It will be very, very hard for me to win. Even if I play optimally, if I do everything right, the policies are not in my favour. So I have this obstacle in front of me and I need to do something about it. It’s not that I will get points out of it, it’s that it will help me in other ways and also hinder my opponents. The victory points are there because we need to determine the winner at the end, but especially when it comes to policies, you want to change them mostly for their effect, not for their points. It’s just an added bonus. It’s more important what you get out of the changed policy.

When I was thinking about key messages in Hegemony, I thought that’s probably it: one often doesn’t care about politics when everything is good. But one needs to care about it because if they change, then it’s too late. I had multiple sessions where people didn’t realise what was happening and in the next year when the policies were in a bad state for them, then they said “oh my god, I should have done this, I should have done that”. But at that point taxation was already up or immigration was already down, so it was too late. I think this is very beautiful in Hegemony.

It is. It also brings out situations where you don’t only want the policy to change in your favour, but after it does, you want to be absolutely certain it stays there and sometimes it’s not so easy.

Let’s say I’m the capitalist and I want one policy to be in section C. I cannot keep it there, I cannot propose a bill to keep it there. You always have this risk of somebody else proposing a bill and go for an immediate vote and changing it in the middle of the round. I even had games where I wanted it to be in C and I would propose it myself to go in B just to keep it in C for this round. [Alex laughs]

For example: I was the state, I wanted to ensure I get high taxation. It was in 3A and I knew that the capitalist would propose 3B and call for an immediate vote. So on one round I proposed it myself to go to B [Vangelis smiles] and so if I win, okay, I get 3 VP. If I don’t, it stays where I want it [Alex laughs] but at least I ensured that I get a lot of money from taxation this round. So next round he realised that and his very first action was to propose for 3B because he played before me as the state. This is a risky strategy and I remember Varnavas telling me “I’m never doing that! Why are you doing it?” But I did it to ensure that it stays where I wanted it for that round.

The Voting System

The immediate vote is very interesting. Initially I thought why is it in there? Is it because you noticed thinks like that and the game mechanisms needed it or was it also something that came from the theme?

In the beginning, we didn’t have it. So at the end of a round we would vote on things and okay it worked, it was still fun, but there was always this sense that whatever I’m doing, it will not affect this round, it will affect the next one. You always had to look into the future to reap the benefits of your actions.

At some point, we felt like we needed to do something to allow you to change things in the current round. That was especially important in the last round because when you play in the fifth round, what are you going to do? Players wouldn’t have any incentive to change anything apart from endgame scoring. But when we realised you could have an immediate vote, we tried it and it worked very, very well, players liked it. It came at a cost, you would have to spend influence in order to do it, so it was not that you could do it all the time. I think the way it ended up like where when you really need it, you have the option of doing it, otherwise you can just propose it and have it take affect next round, I think we found a very good balance between those two options as it is.

So both options are played and you always have this fear of the other person changing something during this round so you need to be careful and always have influence. There have been many times where I was “okay, how much influence does everybody have? Okay, so I’m okay and not afraid” and then a couple of turns on, someone had bought influence and I hadn’t paid attention. They then proposed a bill that I was counting on to stay the same and they already have influence and I don’t. These are very fun and interesting moments when this happens and you need to adapt, you need to change, you need to take it into consideration.

There is something missing in Hegemony which would be very natural in politics games: active negotiation. What it I mean is that there is nothing in the rules that says okay, have negotiation rounds or that you get this card if you do a favour for someone. Even the voting: the first thing people have to do is to declare their side and only afterwards the votes are cast. Why is there nothing in the rules that says “negotiate before you decide” or something like that? Did you notice it just happened anyway so you didn’t have to put it in the rules?

Something like that. To be honest, in my mind, Hegemony was never a negotiation game. Imagine another game where negotiations are part of it: you have to discuss with others, you have to agree to exchange resources, to give cards from one player to the other. There are games where this is a big part of them. That wasn’t one of the mechanisms I had thought of for Hegemony, so I didn’t put it in there. [jokingly] In another world, another couple of guys working on a similar game could probably think of that. But initially I didn’t think about it, so I didn’t put it in the game.

What we realised is that people would negotiate a bit when the time came, on their own. Like “please come with me and I will vote for you next time”. So I thought it would be better to not enforce it, to not force players like “now you negotiate”, whether you want it or not you have to do it. I decided to leave that to each group. If they want to negotiate and make any arrangements, feel free to do so, nothing is binding but you can feel free to discuss it. I liked the way it worked.

I’ve seen players who don’t like negotiating at all or they don’t like getting into that mindset and trying to bluff or backstab their opponent. Some people get very bad experiences out of these things when they happen. So for me, it was not as essential to the game in the form that it took.

As you said, in real life politics have lots and lots of negotiation in them. But the way the game was working, I didn’t think it really needed it. So we didn’t enforce it or put such a phrase in it. Perhaps [chuckles] in the future, we might reconsider or add an expansion or something. But for the main game, it works well as it is and if you want to negotiate, feel free to do so [both laugh]. The game allows for lots of those discussions. Leave it up to your group is what I say. If you want to do it, do it. If you don’t want to do it, perfect.

Yeah, the final system works really, really well in my experience. As you said, it creates a playground but it’s up to the players to decide how much negotiation they want to do.

Also the use of the voting bag: When I first started playing Hegemony, I was wondering shouldn’t it be based on my population whether I have more influence on a vote or not. But you chose this different mechanism of saying no, it’s not your population, it’s your influence, so you do actions to put cubes in there. Did you experiment with other types of voting before you came up with that mechanism?

Surprisingly no! When we started the game, we knew we’d have these policies and players will want to change those policies, so we needed to do voting of some kind. This was actually the first thing we tried. I said lets have it such that players have cubes inside the bag, we draw and that will determine the outcome. It was important to take into consideration that you [always] have at least three parties involved so it wasn’t a decision between two players even in a two player game. We couldn’t chose something that would just work in a two player game, we needed to make sure it works with four players.

We thought of that in the beginning and it worked really well, so we kept it. We did try some other things like for example at some point we had it that each round you would draw a new card and it would be random cubes added to the bag. So in one round, you’d get like 1 blue and 2 yellow ones, [sort of] like how the opinion of the people shifts as time goes by. But it didn’t work that well and it was too random. [Instead] we ended up having players’ actions affect how many cubes will go in, like your population, the number of companies you have, these would determine how many cubes would be put into the bag.

So although we did try a few things for how to refill the bag and when and such things, the bag was always there from the beginning. It was the first thing we tested for this part and it worked well. We were actually commenting [on it]: this is a very fun part of the game! We were play testing and it was always fun and exciting, okay, what’s going to happen? Intriguing!

We would pull the cubes one at a time to add to the excitement and we had play testers comment on that, even early on. I mean a lot of the game was not ready yet, but from what they played, they would comment that the voting process was really fun. So we kept it, and it made its way to the final game.

It would be easy to say there are more working class workers in a society than capitalists, but on the other hand the influence of the capitalists is higher than that of the workers. So it made sense and you also consider it as like having a party represent its class inside a parliament, so you never know which way exactly it will go. Depending on the voting system used in real life, you still may have surprises, you still may have things go out of your way. So we wanted an element of randomness be in it but we also wanted the players to have control over it. I can make sure I put more cubes in the bag to increase my chances of more of my cubes being drawn. However, there is still a chance something unexpected may happen. That’s also why we added the option of affecting the vote afterwards with influence cubes because we wanted to give you another layer of control even after the cubes had been drawn out. So if you definitely want for a policy to change, it’s up to you. You can leave it to chance. But if you don’t want to leave it to chance, you have things you can do to make sure of that.

In one play session where I was the middle class, I build tons of media companies. So every vote that came, I was like okay, I have 12 influence, how much do you have?

[Vangelis laughs] Yeah, and everybody hates you!

Somewhat, yes. [both laugh]

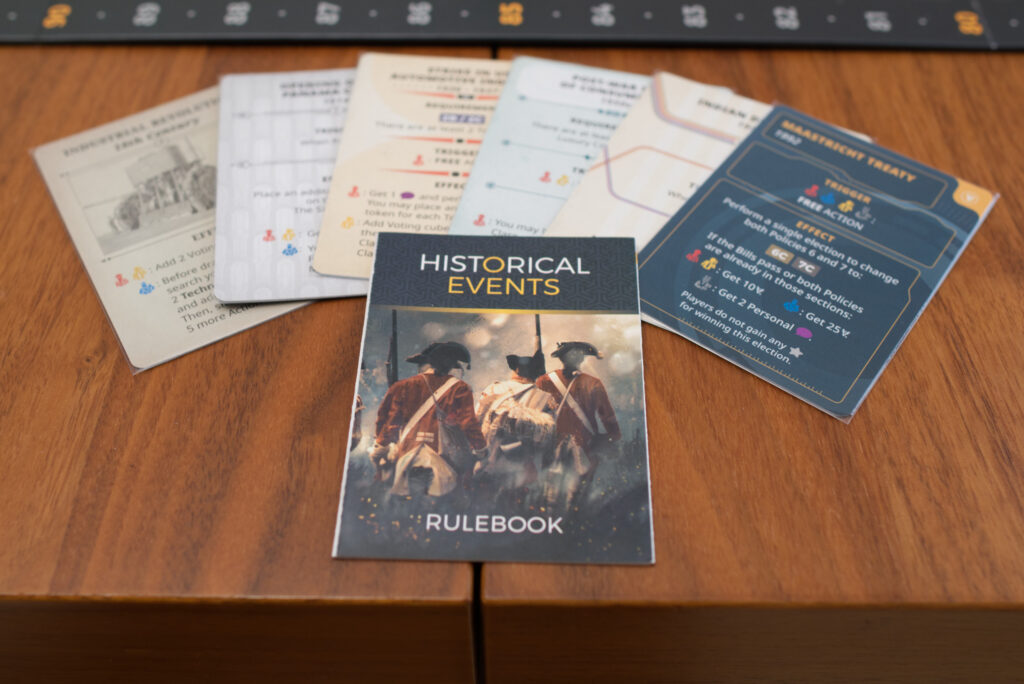

You mentioned something as a side note: there at one point were cards that affected how many cubes were in the bag. Something that surprised me was that there is nothing in Hegemony that actually shows the nation progressing on its own, like events coming in. There is a little bit of that if the state is being played as that tells you this and this is happening, there is for example a famine. But why is there nothing that says oh, the country is currently struggling with this and all players need to react to it?

So the historical events do that to some extent. But for the main game, we already had so many things inside it – lots of rules and lots of moving parts and lots of things to consider – that adding more elements outside of the players’ control felt like it wasn’t needed. Yes, things do happen in real life. We tried to simulate that to an extent through the event deck of the state player.

I think we did consider it at some point but it wasn’t adding that much to the game. The game can be very unpredictable the way it is [Alex laughs and nods] with the players changing the policies or doing something unexpected like the capitalist class selling one of their companies at the last minute or the working class playing a card that will move all of its workers to the public companies. You have these unexpected things happening through players’ action, so I don’t think you need that much happening outside of your control.

Makes sense. Now that you said it: I haven’t personally played with the historic events yet, but yes, it’s probably the thing I almost expected in the base game. But knowing the play length and everything, I’m happy you left it out. [Vangelis chuckles]

This concludes part 1. In part 2, Vangelis and I talk about the economy of Hegemony and how to balance it, running a Kickstarter, what’s up in the future for Hegemonic Project Games, and of course I had to ask him about updates on World Order. Part 2 will be out in a week or two, but in the meantime – if you haven’t already – you should check out Vangelis’ and Varnavas’ excellent designer diary on BGG or their blog at Hegemonic Project Games.

If you enjoyed reading this, please leave a feedback in the comments. Doing in-depth interviews like these takes a lot of prep & research and it’s really rewarding to see that so many of you seem to enjoy reading them. Showing your support helps getting future interview partners on board! You can find more interviews like these in the interview section.