The first games of my virtual Essen haul have started arriving. Instead of going to the convention in person, I opted for watching from home and just ordering a couple of games that fancied my interest. It’s kind of a crapshoot to buy those games without any serious reviews already out but fun in its own way. For example, Sabika must have been the fastest turnaround I ever had in a board game: Got it, unpacked it and set it up with great anticipation … already had sold it the next day. There was simply nothing there that grabbed me and that I hadn’t seen in multiple other games. Shelf space is precious these days and a new game has to compete with the likes of Carnegie, Dune: Imperium or John Company: Second Edition to get to the table. So off it went…

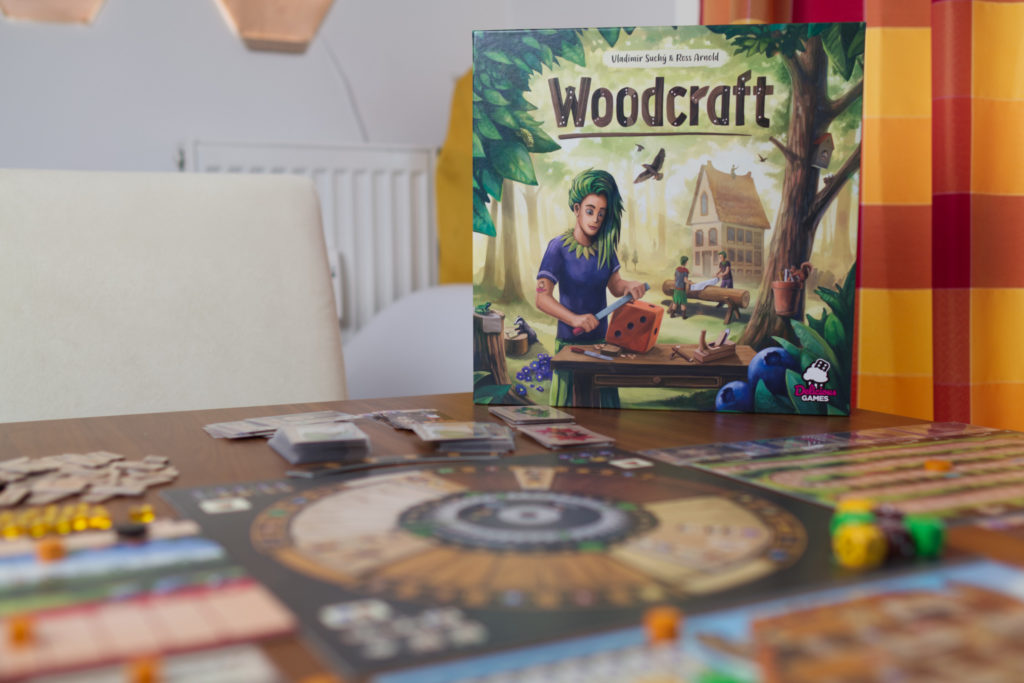

At first, Woodcraft seemed likely to face a similar fate. It has been one of the hottest games of Essen 2022, based on – as far as I can tell – a combination of the name Vladimír Suchý / Delicious Games, some intriguing mechanisms and the not unimportant fact that it actually was available for purchase in sufficient numbers. My personal track record with Delicious Games is mixed: I very much enjoy Underwater Cities and only a little less Messina 1347 but didn’t like Praga Caput Regni. However, all three are very solid games that try to bring something new to the table, which I appreciate a great deal. As a result, Woodcraft was on the top of my Essen wish list as well and when I got it to the table I was … a bit underwhelmed to be honest. But something intriguing happened and by now it has hit the table so many times that I thought “well there’s a story worth telling”!

Setup

In Woodcraft, each player has their own carpentry business in the form of a large player board with spots for helpers, saw blades, tools and … growing pots? How fast do these trees grow and how big are those pots? It’s not the only curiosity that faces the players when they set up the game. The helpers look elf-ish, the art style could be borrowed from a children’s book and your workshop looks like the place where Santa manufactures presents in the off-season. In tune with the theme, money comes in the form of blueberries and victory points are hazelnuts. It’s a strange mixture of being both endearing and off-putting to the non-casual to heavy gamer.

Each player starts with one helper (which provides a small, unique bonus, power or discount), a set of possible upgrades (growing pots, additional saw blades, the ability to glue pieces of wood together, etc), a couple of blueberries, various wooden player markers, a single lantern (more on them later) and a couple of contracts. Both helper as well as contracts can be chosen out of a larger selection each player gets during setup.

The goal of the game is to amass points by fulfilling contracts. Each contract shows the types and sizes of wood needed, a combination of die values in specific colours (e.g. yellow 3, yellow 1, brown 3). There can also be additional requirements like cubes of scrap wood or yellow glue tokens. If one manages to get everything needed, the contract can be fulfilled to score a combination of money, VP, and other bonuses. The tricky bit is that one needs exact numbers. So a yellow 5 cannot be used to fulfil a contract that requires a yellow 4 but there are ways to split and combine dice.

The center piece of the game is the action selection wheel which is split into quadrants. There are 7 tiles that represent the different actions one can take during one’s turn. Besides that there is a score/market board as well as an income board containing the round tracker.

There are a lot of bits and bops in Woodcraft. Organization (and ziplock bags) help here, especially separating all the things each individual player gets. Once one gets the hang of it, setup is done quickly.

The Turn

Woodcraft is played over 13 rounds, which sounds like more time than it is. A player’s turn starts with growing any trees they have planted in previous rounds. Each die in a growing pot increases its value by 2 and is automatically put into the player’s lumber pile when it reaches the maximum of 6. Trees can also be turned into lumber before they reach 6 which can make sense to achieve a certain value one needs to fulfil a contract. However, since planting a tree is an action and thus costs a whole turn, this has to be balanced carefully.

The player can then choose one of the action tiles from the central wheel in order to perform that action: buy wood from the market, sell it, plant a tree, hire a new helper, get new contracts, and so on. When a player chooses an action, they not only get the action itself but also additional bonuses from the position where the tile lies (shown on the outer circle) and in which quadrant it lies (the inner part of the wheel). The action is then moved to the next quadrant and if that would cross the needle of the wheel, the wheel is turned as well. If however taking a tile would require the wheel to turn but the next sector is not empty, the needle cannot be moved and therefore that action is unavailable.

Turning the wheel changes the bonuses that are revealed and the quadrant that is farthest behind produces the biggest bonuses, making actions that haven’t been used for a while that much more worth it. Collecting bonuses is crucial as they can save a player from wasting a turn on getting glue/scrap wood or even gift the player new dice.

Besides the regular action, players can perform a number of free actions: fulfilling a contract is the most obvious one. One can also flip over a saw tile (of which one only has one at the beginning of the game) to split a die into two dice with equal sum (e.g. a green 4 into a 1 and 3 or two 2s). The reverse of glueing together dice is also possible, but only after buying the respective upgrade. Finally scrap wood (=cubes) can be used to increase the value of a die. Together, this makes it tricky to get the right combination of die values and colours for a contract, but possible. One can also spent 3 lanterns to take an extra action which can be really powerful. An alternate way of using lanterns is to spent one to choose an action tile for its bonuses but then perform any type of action the player wants.

There is also a whole separate aspect players may or may not want to invest in: some contracts and helpers provide tools which can be placed on slots in the attic part of the workshop. Placing two different tools next to each other unlocks the bonus shown between the slots, ranging from increased income, better reputation, lanterns to VP. The tools reminded me a bit of how Praga Caput Regni felt: it’s a bonus you want/need to collect but ideally without spending any additional effort on it. It’s great to fulfil contracts for money and then also get a tool that just happens to unlock a little bonus that than triggers something else that gives you another bonus.

As a final step, a player can spent money to invest in “marketing”, a track that gives VP for each step taken. A player can only do a single step each round, so it is important to have liquidity whenever possible.

End of Game

The game ends after 13 rounds. Every couple of rounds, there is a dedicated income phase which is reminiscent of Underwater Cities in that income only happens every 3-4 turns. The income phase also devalues the players’ still open contracts and forces them to play one of the ones remaining from the original set chosen at the beginning of the game. Two of the initially chosen contracts are special in that they allow the player upon completion to put a marker on a shared, public contract which provides endgame bonuses for things like number of helpers hired or level of marketing reached.

At the end of the game, players primarily get points based on the number of contracts they fulfilled multiplied by their reputation, another thing that somehow has to be gathered during the game as if one wouldn’t have enough problems already. Reputation primarily comes from picking certain contracts that are particularly difficult (or provide only little money) and by fulfilling them quickly before they are devalued. The tools area is also a good source of reputation.

Solo Mode

Woodcraft comes with an automa deck but the automa only uses/removes things and does not use a player board or contracts. The goal is to reach 110 points to succeed or 140 points for an excellent result. The benefit of this type of automa is of course the low level of admin work but in general I rather prefer more human-like automas. In the case of Woodcraft however it works because player interaction in a non-solo game is largely limited to snatching away lucrative actions or contracts anyway.

So while not mind blowing, the automa does a satisfying job of screwing with you while you try to solve the puzzle of how to be more efficient with your own stuff.

Conclusion

I have a soft spot for games that are a juxtaposition of theme and game play. While it’s great if a game’s theme fits its mechanisms, there is something fun about suggesting a cute, easy going game when it is in reality really cut throat (e.g. Photosynthesis, Maglev Metro). In the case of Woodcraft, the cute-ish art style might almost have hurt it. During my first play, I had a constant “what is this trying to be” sort of feeling nagging on me and when I finished with 50-60 VP, Woodcraft got close to heading for the chopping block as it seemed just plain boring. The thing that saved it was this ridiculously seeming goal of 110/140 points in solo play. As anyone that has tried solo Underwater Cities can attest, Vladimír Suchý doesn’t joke around when it comes to scoring goals. I think I ever managed to win UC solo once! So when I read what the yard stick is, I was wondering how that should be possible and what was going on.

After a dozen or so plays, I can say for me it was a combination of two things: a tight, snowballing economy and an error prone set of rules and iconography, the former I greatly enjoy and the latter I detest. So lets talk about the latter first: while the rulebook in itself is not great but okay, there are a number of things that are counter-intuitive, vague, or easy to get wrong. For example, each contract has a symbol on it in the top left corner that indicates a bonus. However, that is not the bonus one gets when fulfilling the contract, just the starting row the contract is placed in. Since contracts degrade during income-rounds, the actual bonus one gets is the one next to the row the contract is in. There are also multiple places where a slash is used to indicate an OR but for some reason my brain kept thinking AND (e.g. there are two dice printed on the planting action but you are only allowed to plant one die, the hazelnut contracts allow you to either claim a public contract or get money/VP, not both).

It also took me a ridiculous number of plays to get the buy-glue-scrap-saws actions right. Either I forgot to pay for it or didn’t realise that I get two glue for one blueberry instead of having to pay 2 blueberries for one glue. If you read this and look at the board, you’ll think how the heck did he misinterpret that? My best guess is that it was a combination of learning the game solo and a lot going on in this game, so I had no one to point out the obvious errors I made. But I haven’t had that many problems properly learning a game in years! Speaking of which: this is definitely nothing to play with casual gamers. I tried and we had to abort the game halfway through because my opponent said she still felt lost in all the rules. I would say Woodcraft is on the level or slightly above the complexity of Messina 1347, so literally don’t judge this game by its cover.

Once you are able to internalise the rules though, there is a great puzzle to be had. I just finished a game scoring 170 VP, something that seemed impossible during my first 3-4 plays. It’s rare that a game intuitively feels so loose when the economy is actually really tight. From the initial selection of your starting helper and contracts, you have to plot a plan when and how you will get the right dice before the first income-round. The thirteen rounds of Woodcraft are over rather quickly and the fast pace of the game also contributes to its charm: grow trees, choose action, collect bonuses, try to eek out ever more bonuses using your free actions, spend on marketing, done, next player. It also feels great as a solo experience because you can play it in 30-45min and it is a headscratcher in how to get your engine started in those crucial first rounds.

Your personal economy in Woodcraft definitely snowballs. For example, once you buy your second saw blade or third growing pot, the buying and planting actions respectively get way stronger. On the one hand that can be very satisfying if you manage to pull it off early, but frustrating for new players if they don’t. Most crucially, you have to pick contracts in a way that you stay affluent as income happens only every 3-4 rounds and even then it takes a lot of effort to push up the amount of income you will get. It’s much better to stay in a cycle of get die, split die, fulfil contract than to hope for that one payday every couple of rounds.

The usage of a whole bunch of dice and having to produce exact numbers, not too high but not too lower either, is also fun and something I haven’t seen in other games on this level. Timing which dice to buy when from the market and which dice to plant when is crucial as tiny improvements can make a huge difference down the road. The same applies to the timing of when to fulfil a contract. Should I do it now or rather let the tree grow once more? Right now it’s the perfect value and I would need to saw it later but would then still have an extra die for re-planting next round that I don’t need to buy.

So far I’ve played 10-15 plays and with a single exception all of which solo. So take this next bit with a grain of salt, but I have the feeling Woodcraft works in phases: first is the “how does this work and how is one supposed to get any decent score here” phase which can be quite frustrating or boring. Then it clicks and you get better and better until there is a feeling of having cracked the puzzle. That’s where I am right now. I don’t have the feeling there is much new coming for me and no different strategies to explore, but still it is fun to play. I have come to really like that fact that I’m panicking on where to get two more blueberries from when the images on the contracts of what I’m building are so cute.

While I haven’t played non-solo yet (apart from that one half-played session), my fear is that multiplayer will not bring much change to the game and it will in large parts feel multiplayer-solitaire to me. All player interaction is restricted to largely snatching away actions, contracts, and helpers and the automa does a good job of simulating that. What I can see is a potential third phase when playing with opponents that also are well versed in this game. The economy is so incredibly tight that it should be easy to throw a wrench into another players clockwork, but I’m not sure how much that will hurt oneself.

To sum it up, I think this is a keeper. Interesting mechanisms, plays well solo, looks fun. I don’t think I will get it much to the table in the future with what other games are waiting to be played. But I would miss it if it weren’t in my collection and it has a good chance to be played solo from time to time, the puzzle is that enticing. I’ll add updates to this post when I get the chance to play this multiplayer. There are already a number of friends lined up who are interested which is always a good sign…