Two years in board gaming really feels like an eternity! I realised this more than ever before when I finally receiving my copy of Unconscious Mind a few weeks ago. Hard to believe, but it’s been two years since I decided to back this game, mostly on the strength of its visuals, theme, and because a number of YouTubers at the time seemed genuinely impressed. I also was still in my first year of writing reviews and this gorgeous game seemed like something that would be fun to write about, so I backed it. And the wait began …

A lot has changed in those two years! I’ve lately found myself much more attracted to twenty year old Splotter Spellen designs (e.g. Antiquity, Indonesia) that play amazingly than blinged-out crowd funding projects. My fair share of Kickstarter duds has taught me to mistrust any form of “preview” and my ever-refining collection has made it hard for any new game to get a permanent spot. Ask my friends: some very popular games I got haven’t even made it past the one month mark! Gosh, there are some amazing games out there, and I’m super happy to have quite a few of them in my collection by now. But it induces a constant “why should I play this if I could be playing X instead?” that on the one hand is healthier consumerism and on the other hand bad for someone who enjoys writing about new games.

So things promised to become interesting: one of the most gorgeous looking games in a while vs my now much lower tolerance for mediocre gameplay. How would Unconscious Mind fare?

Disclaimer: Over the years, I have talked with many friends and acquittances that work in the field of psychology/psychotherapy and that has given me a huge amount of respect for this profession. I also know there is a reason that we for example no longer call those seeking help “patients” but clients and some terms might have negative connotations. I’m trying my best to avoid those where I know them, but of course some things might slip through as I’m not an expert.

Unboxing

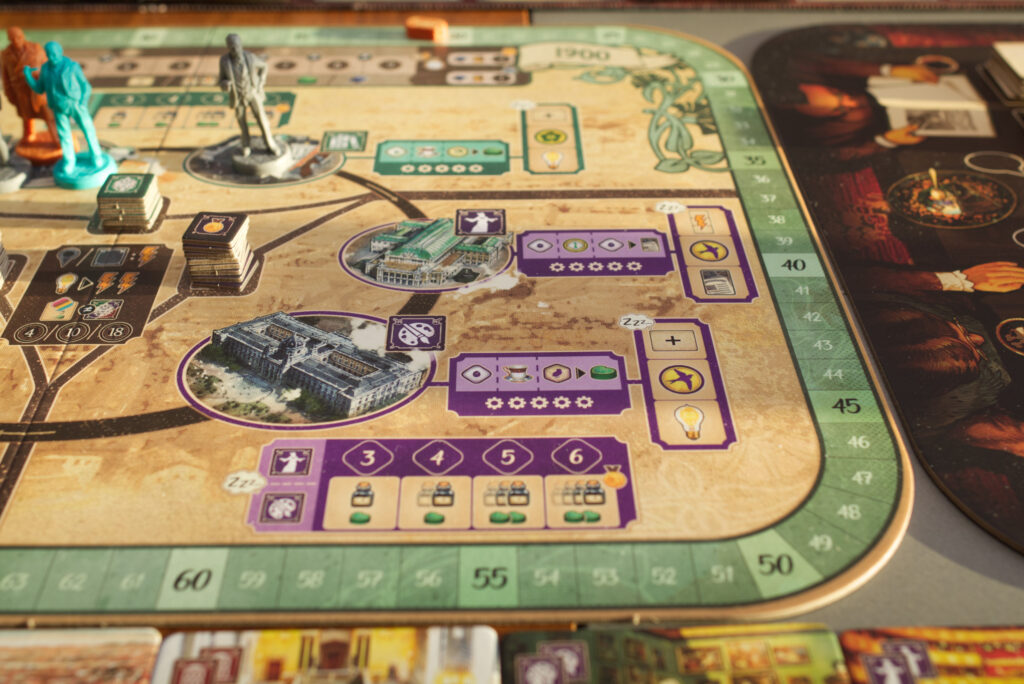

A big part of the allure of a game like Unconscious Mind is its production. So let’s hold off on the actual gameplay and bask in the glory of all that comes with that all-in pledge. First of all, that box cover is striking … though it only took like two seconds before the UV layer had its first scratches and minor dings in it. Its size is comparable to a Castles of Mad King Ludwig Deluxe: a Ticket to Ride footprint with double the height. Note that this is the ID-lite pledge where everything was fit into a single box. There is also a version with a smaller box that only contains the base game and keeps expansion content in separate boxes. In hindsight, I would likely have preferred that one, but I’m getting ahead of myself …

On the inside, we find multiple trays. One holds the deluxe minis for the player figures, some further minis used in optional modules, an improved version of the ink bottles used as markers on the player boards, as well as a small playmat for the shared card display. The playmat is quite nice and helpful, although I never managed to get it NOT to curl. But the quality of the print and material is really good, unlike the playmats of some other games where the graphics can be all blurry.

The larger second tray is for expansion content plus various stretch goals. Finally, the bottom layer that stays in the box contains everything needed for the base game and solo mode. On top of it all are of course the rule book, some nice dual-layer player boards and quite unusually two (not one) different main boards.

There were two things that immediately caught my eye: 1) how gorgeous those dream cards looked … and 2) how ugly that Vienna board is! It’s rather abstract/functional and sticks out like a sore thumb, like an afterthought that was added late and immediately broke the emergence for me. The plastic of the top trays is also rather thin and already had misshaped. I assume that’s a result of that the publisher originally hadn’t planned for an all-in-one-box solution and only during the campaign had added it when a lot of requests came in.

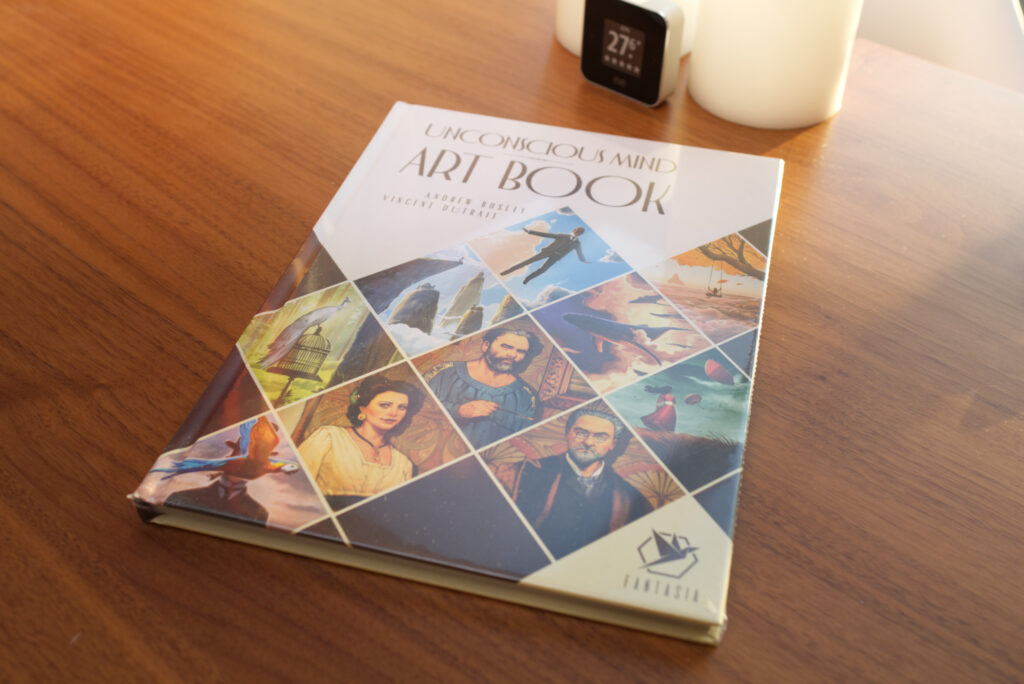

I also got the second, larger playmat that replaces one of the main boards, optional holo-foil cards and art book, more on those later. The other thing to note are the art-sleeves which feature the same beautiful art that’s also on the back of the cards and therefore are quite pointless. Normal sleeves would have done just fine. As you can see, I had big hopes for this game and might have gone a bit overboard here. 😀

Setup

Unconscious Mind is quite the table hog and so setup takes a moment. There are two main boards, one for the main action-selection mechanism showing various people around tables, the other the Vienna board on which the player minis and Sigmund Freud will run around in circles to get coffee and other bonuses. Each player not only gets a dual-layer player board and accompanying ink bottle marker – which will also be on a loop to trigger actions – but also another smaller dual layer board where two clients will be waiting for treatment, and yet another third dual layer board where insights (represented by glass beads) will be shifted through various levels to ultimately be used to cure said clients.

Then there are tiny district markers, treatise tiles, notebook tiles, location tiles, reputation markers, grief layers, two types of clients, two types of dreams, research cards, transparent insights, insights in player colour, idea pieces, bright idea tokens, … the list is quite long. Overall setup isn’t too bad, there is no “remove these tiles if you have a lower player count” or anything annoying like that, but it still will take a few minutes.

The Turn

On a player’s turn, they have three basic options: state an idea (=trigger an action on the meeting table board), recall ideas to get the respective tokens back (and get some additional bonuses of course), or treat clients (providing yet more bonuses). Most of the time will be spent presenting ideas and thus gaining insights until the player has enough to cure a particular client of theirs, usually only defaulting to recalling ideas once one runs out of them for the moment. As you might notice, I struggle to keep the theme up already because the Euro-gamer in me just sees it as what it is: do actions to get resources to match contracts to get bonuses. But to stay with the theme, let’s start at the end and what’s it all about: clients.

The main thing to achieve in the game (ignoring of course the ultimate goal: victory points) is to cure clients. There are two types of clients, routine clients that provide in-game effects and case-study clients that provide end game scoring … wait! What is it with this game? I’m already falling back to mechanics! I’m really sorry, I’m trying, but sadly clients are just represented as a means to an end here. For example, they have something they want you to treat but then wait patiently up to eternity for you to do so. This might as well be people in a drive-through that want you to get the fries ready and thus complete their burger menu, the only difference being that patrons of a fast food chain would leave if the fries weren’t there when the burger has already gone cold.

Each client card shows their effect and VP at the bottom of the card, and 2-4 green hearts on the left side of the card. These hearts represent the amount of help they need from us. That those are only on the left side of the card is important because every client also comes with a transparent grief layer which shows additional hearts on the right side of the card. Combined, this creates the total amount of treatment they need to be cured and which is marked with a round disc on a track above the client on the small dual-layer board. For every heart of treatment we will be able to get, the marker goes down. Once it hits a specially marked step, the grief layer is removed and the client’s effect gets activated. Once the marker hits zero, the client is fully cured, moved off to the side and immediately replaced by a new one from the common display. The player here has free choice whether they want to pick another routine client to bolster their engine or start going for so called case-study clients to build up for end game scoring. Again, the human aspects of clients are almost completely missing. There is a buffet of options on display and the player picks based on difficulty of treatment and reward to be gained.

The main form of treatment is analysing a client’s dreams, two of which will come with each client. The latent dream is drawn blind directly from the respective deck (green back) while the manifested dream can be chosen by the player … which also is kind of odd thematically-speaking now that I think of it. “I accept you as a client and you will be telling me about your weird bird-dream! You don’t have one? No problem, now you do!”.

The reason to choose one dream over another is two-fold: on the one hand, they require a different combination of insights of various levels of complexity (e.g. a level 3 red one and two level 1 green ones) and some may show a category icon in the top-right corner. If that category matches that of the client’s grief layer, an additional free treatment point is to be had when resolving that dream. Or in other words: match symbol if possible and otherwise take a dream that will have enough hearts to cure the client but not require too many insights that are hard to get for you.

I’ve mentioned them a number of times, so let’s look at the insights: each player has a circular board that shows three sectors, I’ll just call them red, green, and purple and skip on the theming because for all I know, they just do the exact same thing. Through various actions, a player can get an insight of a certain colour and level. For example a red circle means a top-level red insight where a diamond shape indicates the lowest level of insight. Note that the number of insights a player can have is limited by the number of glass beads but there are ways to unlock additional ones on a player’s other player board. I mention this as I multiple times ran into situations where actions would have allowed me to gain more insights but I couldn’t take them, and that really hurts!

The various actions in the game allow a player to either gain new insights, move them up or down (the latter to pay for some effect), or change their colour. There are also free actions that a player can do at any time which allow raising/changing insights by spending coffee, the generic currency of the game that would have been “coins” in many other games. So to cure a client, one primarily needs to do actions to get or level up insights of the right colours, then spend them to resolve dreams, and those dreams provide treatment points that are hopefully enough to cure a client.

Stating Ideas (a.k.a. The Action Selection Mechanism)

So we now know what we need: insights! But how to get them? At the very core of Unconscious Mind is a rather basic action selection mechanism. On the meeting board, there are nine actions. Three allow players to pick up tiles to improve their own action (more on that in a second), two to gain or improve insights, two to gain and play research cards or do larger publications, and two to move and activate figures on the Vienna board. On their turn, a player can place one or two of their speech bubble tokens on a single spot. Thematically, they are supposed to be ideas that are exchanged/discussed, but there isn’t really any player interaction here except for blocking. The player aligns the pointy bit of the token to indicate what action they want to trigger and then execute it that many times. That’s pretty much it. If one doesn’t have enough of those tokens left, there are one-time use light bulb tokens that can be used instead to avoid having to spent too many turns on recalling speech bubble tokens all the time. Typical Euro “I block that spot and you can’t do it” fare. For lower player counts, outer columns are locked off to make the board tighter.

What makes things a bit more spicy is that the row the tokens are placed in also indicates one to four ink bottle icons. After performing the regular action, a player then moves their ink bottle marker on their personal player board that many spaces and activates that row of tiles. Each player only starts with a single tile but with the respective actions on the main board, they can shop for further things and assemble their own little engine. There isn’t anything dramatic in there, it’s mostly about converting or improving insights and/or exchanging to or from coffee. Still, it feels quite satisfying if one can do a great action on the main board and then time it right so the ink bottle also triggers a whole slew of tiles. Note that the ink bottle always runs on a loop and when it crosses a certain spot, the player automatically unlocks a fourth, fifth, and finally sixth idea token.

Since that alone as a core mechanism would be a little underwhelming, in typical Euro-fashion two additional “mini-games” have been bolted on. Publishing consists of getting research cards via various means throughout the game and then activating them, which usually gives the player an immediate bonus. Once a player has the right combination of research cards, they can use the publishing action to publish a treaties which is lovely represented by slotting the cards under the matching cardboard tile to make it complete. One nice touch is that a player can cite from the publications of others players to complete their treatise, removing cards from their books in exchange for victory points and one of those light bump tokens. Publishing not only provides a substantial amount of VP but also two location icons, which becomes important for the other mini-game.

On the Vienna board, there are there districts (=colours) with two locations each. If a player uses a main action to move either their figure or Sigmund Freud, they can activate the bonuses at that location up to five times. The exact number depends on either the amount of people standing in that location or the number of matching location icons the player has gathered via research papers, treatise, treated clients, etc. At first, this seems hardly worth the trouble but towards the mid-to-end game when a player has collected more of those location icons, it can actually become a profitable action, especially considering one can do it twice in one turn by placing two of those speech bubble tokens on that action. A lot of the time though, moving on the Vienna board feels inefficient and pointless. There are usually better ways to get to those resources. However, the location where a player is in at the moment when they recall their idea tokens matters when it comes to gaining additional bonuses. If things go well, a player might not only recall their idea tokens and gain coffee (a standard part of that action) but also place one of their insights on the district track. Depending on the number of icons of that district the player has collected, this can provide up to two additional treatment icons AND an additional movement of the ink bottle with subsequent activation of all those juicy tiles on the player’s board.

That said, the Vienna board still felt very much like a side attraction to me, something you try to use for your advantage if you can during the call back action but otherwise largely ignore in favour of treating clients and doing other main actions.

Game End

The game end is triggered once Sigmund Freud’s reputation marker reaches the end of the track at the top of the Vienna board … which is yet another completely different mechanism in the game. Mostly by fulfilling certain achievements (e.g. first player to cure three routine clients, publish two treatise), a player increases their reputation and also with that automatically Freud’s. If Freud hits the ten, the game end is triggered.

So what’s reputation for? Well, the first and second player on that track get additional VP for their clients and treaties but in the grand scale of things, this didn’t seem to have that much of an impact. The other thing is that there is an ink bottle spot where no actions are triggered but instead the reputation track is activated. Only then does the player actually gain VP based to their position on the track and a small bonus shown at the bottom. At least for us, we avoided that ink bottle spot as much as we could. Triggering the normal tile rows on the player board seemed that much more powerful to us.

At the end, players mostly get points for the case-study clients (which are multipliers for things like having collected certain location symbols), having collected different location icons, having placed insight markers in different districts and things like that. In a number of cases, awarding VP for this and that felt to be mostly there so players would use that part of the game at all. The bulk of points definitely comes in-game from curing clients, publishing treatise, and from the case-study clients at the end.

Nightmares Expansion & Stretch Goals

Well, this is a Kickstarter, so there are tons of small modules and stretch goals that can be added. I didn’t find any of them particularly exciting while some seemed to disrupt the balance of the game. The one to highlight here is the Journalist which can be used as an additional character on the Vienna board so it’s more worth it to use the travel actions in the early game. One of the designers has mentioned that it’s recommended to play with it when playing 2p but no such hint is in the rules. In some way, this module felt quintessential crowdfunding to me: there’s a whole new mini + wooden figure (in case players didn’t get the deluxe components) for what in the old days would have just been “use a player colour that’s not in use”.

The main expansion “Nightmares” replaces the normal insight player board with a different one that features cracks. These a) makes it impossible to change colour of higher level insights and basically allows changing low-level insights into all-powerful “mad insights” (by moving them into those cracks) that can be used as any level. The drawback is that this usually results in the player getting madness tokens and at two times during the game, player’s lose points based on how many tokens they have. There is however a benefit to all this madness: the more madness tokens a player has, the more special abilities they can use such as walking Freud’s figure on the Vienna board backwards instead of forwards.

There is also a new type of dream that upon resolving immediately brings the client to the point where the grief layer is resolved, independent of how many treatment points that would have cost which is especially handy for complex, high reward cases.

Overall, the expansion is nice and integrates well with the base game, but just adds “more”. I didn’t feel a major improvement playing with it but I wouldn’t mind playing with it either. As a potential buyer, I would say you’re okay to skip on it unless you really love the game and just want everything there is to this world.

Extra Stuff

What really surprised me was how lukewarm my feelings were for basically everything besides the base game. The deluxe ink bottles look stunning, but the minis for example just weren’t my cup of tea. Probably some thin coat of shading to bring out the details would help a lot, but they just felt cheap to me. There’s a metal token to replace Sigmund’s reputation marker that I also left it mostly in the box because it felt out of place for me. That small playmat for the card market was helpful because you’ll be constantly picking up new cards from the display, but that’s about it.

The larger playmat for the Vienna board and meeting room board I unrolled once and then packed away again. Somehow they just felt superfluous. With the smaller playmat, there is the advantage of sleeved cards no longer sticking to the table, but that issue doesn’t exist with the wooden tokens on the meeting room board or the minis on the Vienna board. Plus the Vienna mat is larger than its normal counterpart as it has dedicated spots for the achievement cardboard tiles.

Same for the holo-foil cards: unpacked them and immediately decided that I rather play with the normal cards since they look so stunning anyway. The foiling also is a bit much and in the wrong angle just completely overshadows the beautiful art beneath it. On some card the effect works great, on others it just looks tacky.

The art book was the one thing where I really thought if I should open it or keep it in shrink until I’ve figure out what to do with the game. That beautiful art is definitely the main selling point of Unconscious Mind and having an art book for it is amazing. On the other hand: how often does one actually look through those?

Solo Mode

The solo mode of Unconscious Mind uses a simple automa card deck and special action tiles. During setup, all slots of the player board are filled with those dedicated tiles and whenever the automat triggers a row, the next tile is flipped over and becomes active from the on forward. In its base level where none of the tiles start flipped, I found the automa often would do very weird and inefficient things that felt broken to me. However, as soon as I started playing with the first column of tiles already active, things much improved.

The other element is the card deck which mainly is there to block action spaces at random and produce a number for how many steps the automa’s ink bottle should move. In the end, all the automa does is convert stuff it gets into coffee and trades four coffee for a treatment point, all of which it divides between the two clients it has. Except for one special action, it doesn’t care about the dreams and thus cures clients in a more direct way.

Overall, I quite liked the automa. It doesn’t do anything special, but it works and gets out of the way. Part of why it works well though is because Unconscious Mind is in large parts a very multiplayer solitaire experience of crunching through a conga line of clients. Even in my multiplayer games, I rarely really took much notice of what my opponents were doing because in most situations, it just didn’t matter.

Conclusion

Okay, let me get it out of the way so we can focus on the actual game: the artwork is stunning, absolutely gorgeous! What Andrew Bosley and Vincent Dutrait have created here is a masterpiece. Let’s ignore the quite ugly Vienna board and the somewhat disappointing minis, but everything illustrated by those two is lickable tasty! Pretty much every dream card I would be happy to frame and put on my wall, the contrast and interplay of Andrew and Vincent’s art styles works really well. So artwork: big fat green check. Overall production: has its light and dark sides.

Once I had pushed the thought of all that beautiful art out of my had for a moment, one of the main things I was thinking about was if Unconscious Mind is a thematic game or one merely inspired by a theme. This is something I’m thinking a lot about right now as can be seen both in my recent conversation with Tomas Holek (designer of SETI, Galileo Galileo, Tea Garden) and an upcoming episode of Origin Stories with Dani Garcia (Barcelona, Windmill Valley, Daitoshi). Where I’m at so far is that for me, a truly thematic game makes me feel like I’m doing what the game tries to represent. That it makes me go “ha, I might want to pick up a book about that!”. And that the theme helps me to intuit the rules. I read something interesting regards to Splotter games – I think it was for Roads & Boats or Antiquity: you play the game, you wonder what a rule’s detail might be and you make an intuitive guess based on the theme … and it turns out it’s correct! The system of rules is so coherent that a player can derive a lot of the details by just what feels logical and still get a well working game out of it.

I know Unconscious Mind has been heralded by a lot of people as a very thematic game, but for me personally, this isn’t the case at all. It’s a solid, well designed Euro that could have been branded any number of other themes without anybody noticing: fast food chain business, architecting houses, bicycle repair man. It would have made just as much sense (or more) to have a completely separate side board with people sometimes running around in circles to get stuff and replacing one order with the next as soon as it completes. All this talk about exchanging ideas, analysing dreams, curing clients. Yes, it uses lingo and elements from psycho analysis, but is it truly thematic?

What bugs me is this incoherence between the different aspects of the game (treating clients, publishing, doing something in Vienna, abstract ink bottles moving) which are only held together by symbols and bonuses. One could easily imagine one of them having been cut from the game completely. But I’m mostly struggling with the role the clients play: forgettable, interchangeable, and only a means to an abstract end in the form of victory points. I would have loved the treating process to be more nuanced, the clients to have some reason that makes me really care about helping them quickly … besides me trying to get them off my sofa.

So putting gorgeous art and – for me non-existing – theme aside, I’m afraid there isn’t much reason left that makes me want to play this game in favour of so many others. As a said, it’s a well designed, solid Euro. There is as far as I can see nothing broken, no OP strategy, and the biggest ding I can give it is that the game arc always feels the same to me: quickly get tiles to boost up your engine, avoid moving on the Vienna board in the first half, try to churn through clients as quickly as possible and then see if doing research is in the stars for you or not based on the tactical situation. There are no paths of exploration, nothing that makes me go “next time I will try X” and want to get the game back to the table.

I won’t go into more details here because I think my personal feelings are clear and – as always – it’s up to you to decide if they resonate with your taste in games or not. Let me stress: There are many, many people very happy with this game and for them it feels highly thematic. For me it doesn’t, and that’s totally okay. I’ve sold off my copy to someone that was noticeably very happy to have been able to get their hands on it. Unconscious Mind is a solid Euro, it’s pleasant to play with little-to-no AP, the artwork is gorgeous, works well solo. I see Unconscious Mind working well for example for couples that enjoy multiplayer solitaire games with great art and no direct ways of conflict that could ruin the shared pleasant playing experience. My main recommendation – if you decide to pick this up – would be to go retail and skip on stretch goals and the expansion. Similar to the Redwood all-in box I at one point owned, it’s a great collector’s piece to have but if we’re honest you can get basically all of the gameplay and most of the stunning art for a much cheaper price in a smaller package.

Thank goodness you are on the non-thematic side with this one! (The title scared me :D)

The fact that so many people find this game highly thematic shows a true devaluation of the word. I find it rather annoying in general, but this game in particular rubs me the wrong way. If you take on a theme like that – psychoanalysis & mental illness – you really have to do better than curing clients with “treatment points” and removing “grief layers” with generic contract fulfillment. I find it embarrassing frankly.

I actually wrote a piece about theme triggered by this (and Luthier, another one of those) but I’m not sure I’ll actually post it on BGG. I’m afraid I get too upset when I have to deal with defenders of the “theme strong” kickstarter crowd. I saw you backed out of your own thread on BGG – can imagine.

Anyway, thank you for the thoughtful piece again! I appreciate how you share your tastes have developed since two years ago. Interesting read.

Thanks Ivo. Yeah, that BGG thread actually made me sad. It was clear that especially one of the designers was implying things I hadn’t actually said in an attempt to discredit my opinion, so I jumped out. No sense in reasoning with people that are unreasonable …

+1 support to this idea. I am also in the camp that feels like this game has no theme whatsoever. It is just pushing colored bits around according to iconography.

As you mentioned, it could have been fast food, cows in a field or CIA missions in cold-war Yugoslavia.

For all the beauty people rave about with the Dixit cards, they mean exactly nothing for gameplay. You look right past it in order to find the icons that are important to you in that moment. I find that sad, because there was obvious artistic talent invested for something that most brains just completely skip.

anyway, thank you for your review and offering such an honest perspective.