Sometimes, surprisingly, the BGG games market can be a source of inspiration for me what newly released games to try. With every pre-order or crowd funding project that is being fulfilled, someone inevitably will have had their life situation changed between backing and receiving a project … or they found that they didn’t get what they had originally hoped for.

In case of GMT’s recently released “I, Napoleon”, I had been happily oblivious of its existence until I stumbled upon a for sale listing. I don’t follow GMT’s p500 pre-order system but often had wondered if I should. Conflict games are not my cup of tea, but I’m increasingly interested in historical or political games. And so as I saw the entry, I got curious what might be behind that cover. A solo only game? From GMT with a topic that is actually of interest to me? And its playtime isn‘t in the double digits hours? This might actually be for me!

Visuals looked interesting too, which always helps. I have written about GMT’s previous solo-only game Mr President, which was an interesting concept – covering all aspects of a presidency from local politics to international incidents in a single game – but was just too much for me. Too many reference sheets, too many counters, too many booklets one had to constantly refer to. One basically needed to rent an additional room to be able to play it or otherwise most of the tables in one’s flat would be out of commission for a couple of weeks. So not for me, but it scratched an interesting itch: a solo-only game that is meaty enough to have a substantial playing experience and not just be over in an hour, something to sink one’s teeth in. I haven’t found many of those I actually enjoyed. Would “I, Napoleon” succeed where many fail?

Setup

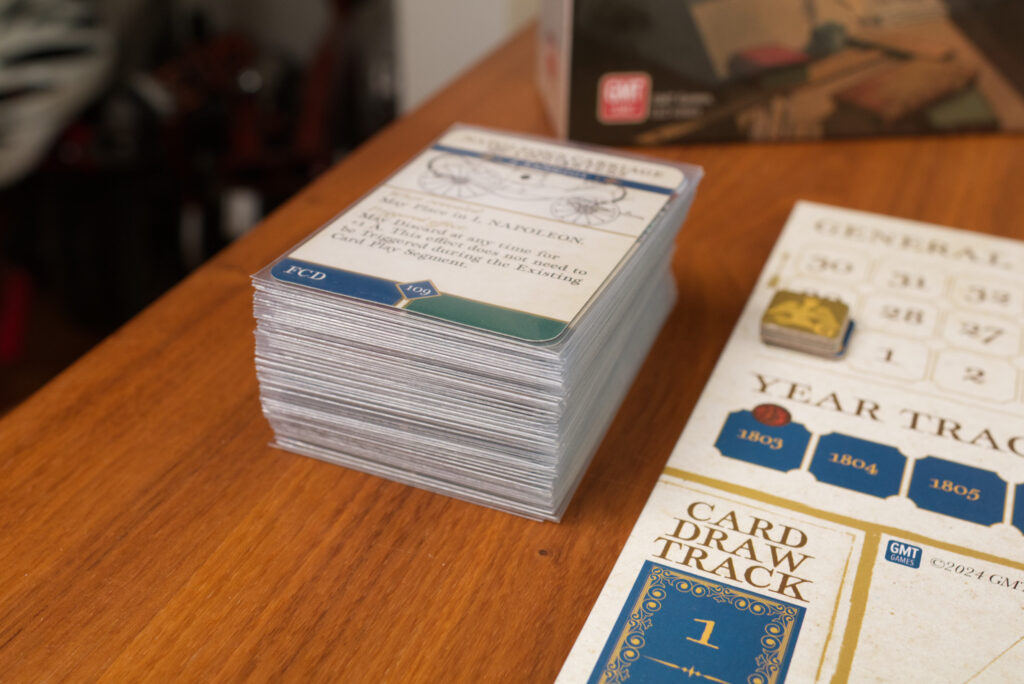

Considering its price of 65€, there is surprisingly little in terms of components to be found in the box: a rather large 8-panel main board, a few cardboard counters, a single D10, a very basic cardboard insert, and 222 cards. That’s it. This is Napoleon Bonaparte’s life.

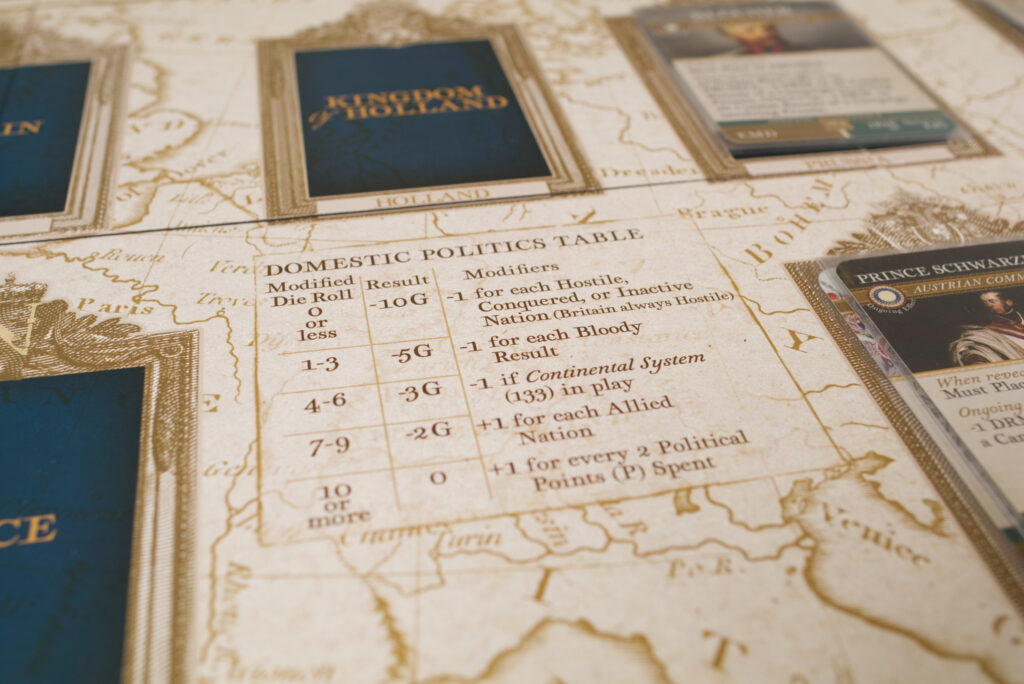

The board shows a rather abstract view of Europe: it mainly consists of boxes representing various countries (e.g. Spain, Britain, Austria), functions of Bonaparte’s associates (from wife to chief of staff), and various elements that affect combat. Each box will hold one or multiple cards during the game and can be mostly thought of as labeled storage areas to make it easier to find and reference cards. There is no spatial relation or connection of importance between the boxes and once a card is placed, it will stay in its box until removed from play.

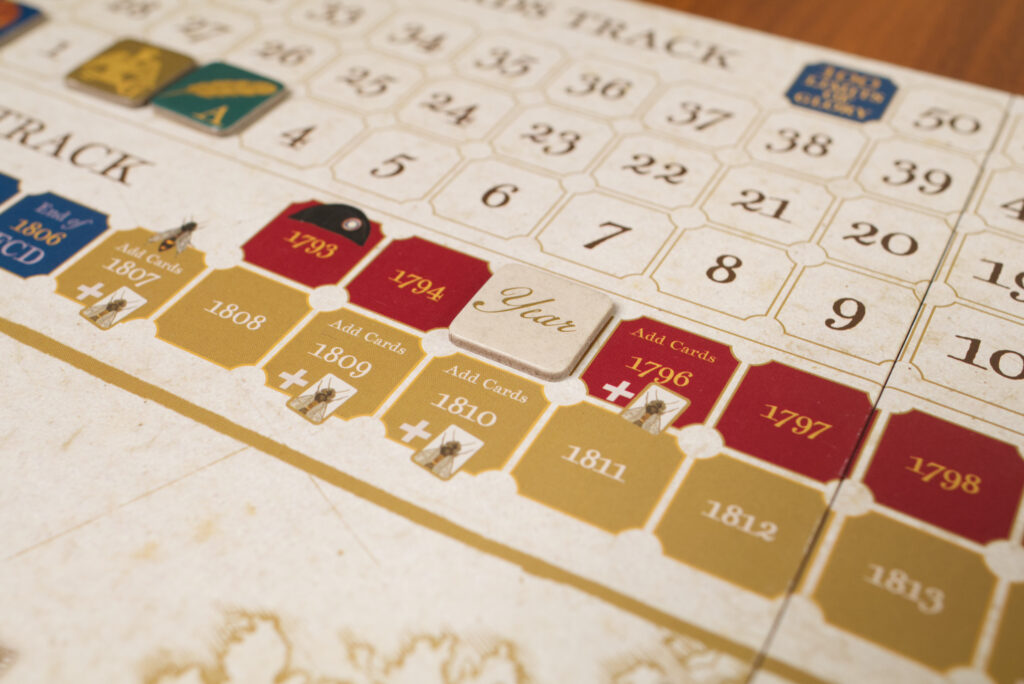

There is a 0-50 track in the top left corner of the board that’s used for the four currencies of the game: Glory (G), Administration (A), Politics (P) and Diplomacy (D) as well as a year track underneath it and a card draw track on the far left. Some of the included cardboard counters are used as markers on the tracks but most of them are visual reminders of card effects such as income.

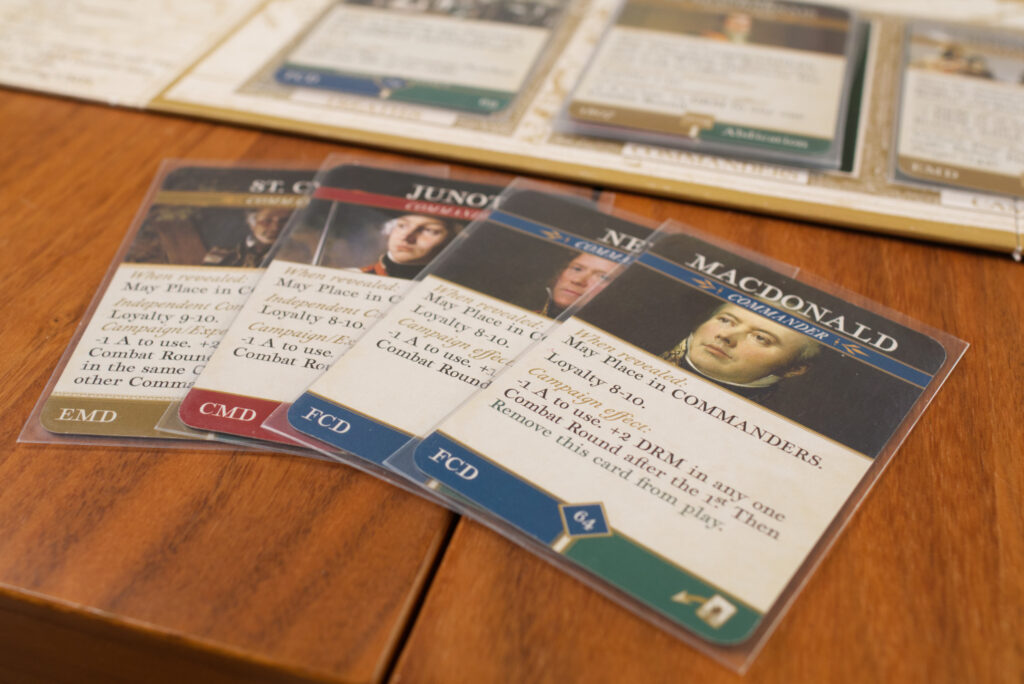

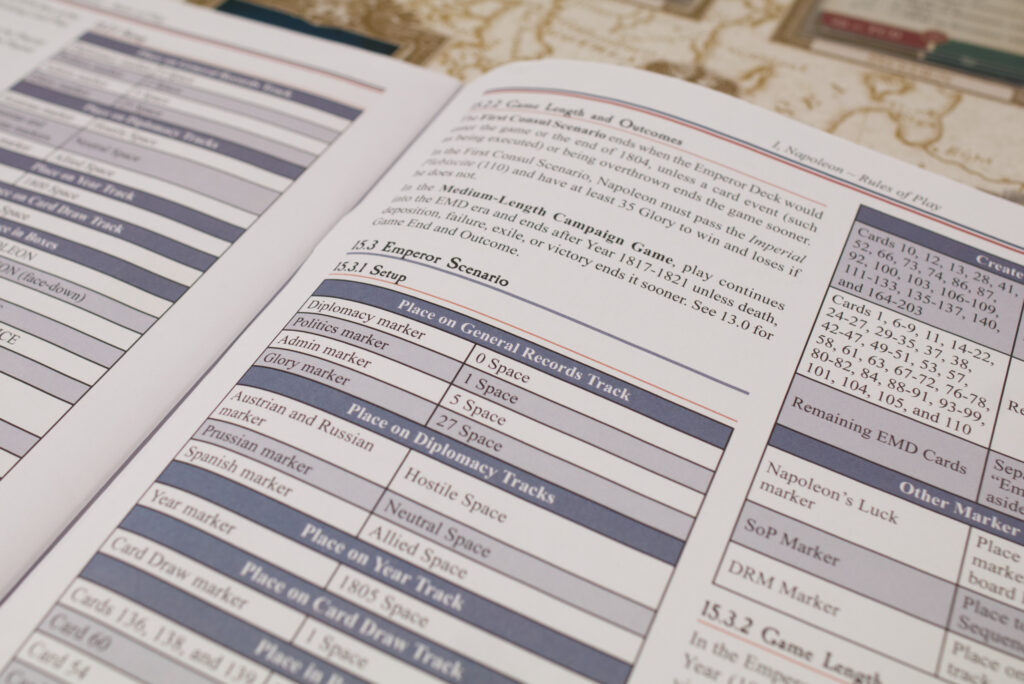

So far, everything mentioned has just been accessories. The heart of I, Napoleon are the heaps of cards, which have to be split into various piles during setup. Based on the colour of their bottom bar, they can easily be split into the three main phases of Napoleon’s career: commander, first consul, and emperor, usually referred to by their abbreviations CMD, FCD, EMD. However, these three decks now need to be further split based on the number printed on each of the unique cards. For this, the game comes with a set of divider cards that specific the ranges of cards needed (e.g. 34-56). All of this might seem daunting at first but with a little bit of practice can be done in less than five minutes.

Once done, we shuffle the first small pile of cards for the CMD phase, set the card draw marker to 1, and launch into the year 1793 …

Income: Use A & D to Get P & G, U C?

Each turn starts with income, which is provided by the cards in play. Administration (A) and Diplomacy (D) are reset to zero every turn – a rule that’s particularly easy to overlook – where Glory (G) and Politics (P) can be accumulated or spent over the course of the game. Administration represents Napoleon’s ability to give orders to other people, act himself, or activate strategic abilities. It usually ranges between 1-6 per turn depending on Napoleon’s experience and staff. Some turns, that is plenty, others there can’t be enough of it.

Glory on the other hand is Napoleon’s life line. During the early phase of his career acting as a commander, he’ll be accumulating glory and once becoming first consul will depend on it. Military success will add to his glory while defeat and factors like useless family members or foreign opposition will continually cost him glory. The early commander phase mechanically speaking acts as a safe space where running out of glory has small to no consequences. But starting when Napoleon becomes first consul, ending up with 0 glory is an immediate auto-loss!

Deck Management … No, Not That Kind

After taking income, the active card deck is updated. The biggest amount of cards are added by triggering two specific in-game events: one that makes Napoleon first consul and the other when becoming emperor. And we are not talking about a few cards, it’s a whole stack of them! In addition, during certain specially marked years, new cards are inserted into the deck and others will be removed. E.g. a particular event might happen if that card is drawn before 1796, but removed from game (=pulled out of the active deck) without effect as soon as the year 1796 starts. In a similar fashion, playing certain cards can require going through the deck and fish out other cards that no longer make sense. One can theoretically also keep the cards in the deck and remove from play upon being drawn, but that is even more difficult to keep track off than the alternative.

The bottom right portion of each card shows under what circumstances it might have to be removed: a year, a card with a certain number is played, when it itself is played, or when a different era (first consul or emperor) is reached. In general this works well, but there can be situations where one plays a card and can’t be quite sure if the referenced card number in the bottom right corner was already played earlier in the game and thus is now in the ever growing discard pile, still to come, or somewhere on the board. The fact that only the number and not its name is specified makes this even harder. 73? Did I already see 73? What was 73… ?

Card Play

After updating the deck, the main portion of the turn starts. A new card is drawn and the player has the choice of playing it or discarding it. These are things like hiring someone as a commander, events that occur, or spending administration to re-organise France. The majority of cards though don’t really give the player a choice. They contain a must-statement and can range from just having to add a card to a particular box or rolling a die to see if the game is over because Napoleon has become victim of an assassination attempt.

In general, there is a really nice flow to this portion of the round, but that comes at the price that few of the decisions made here are decisive. At times, the card phase feels more like a seeding for things to come. I had rounds where card play literally took me only 20 seconds because I only had to draw the minimum of 5 cards, most were mandatory cards and the rest I already was familiar with and knew what I wanted to do with them.

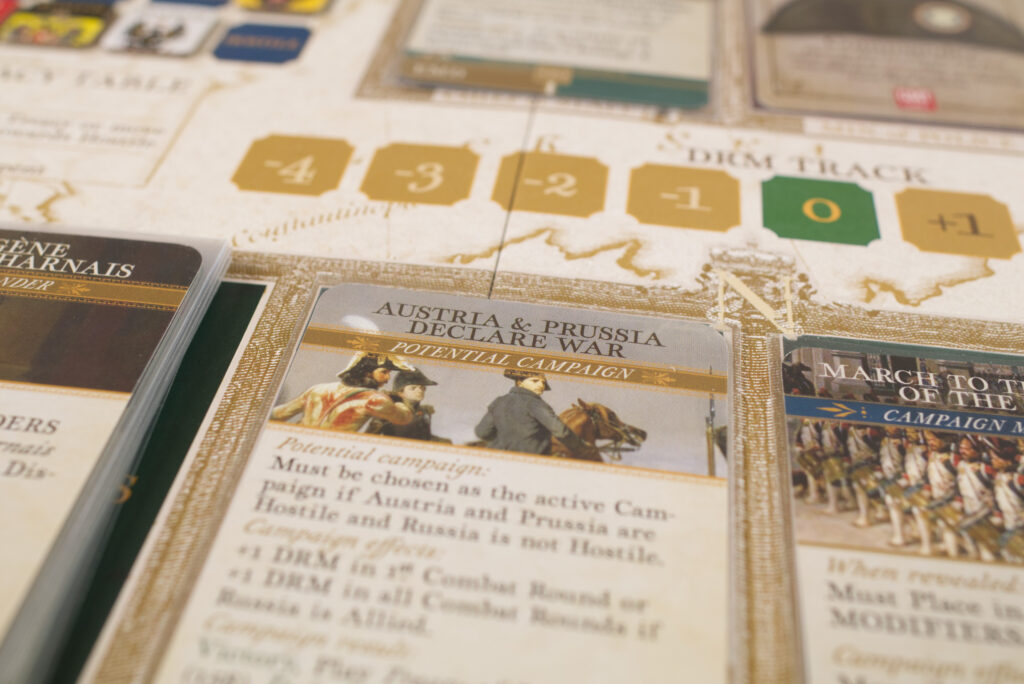

One of the more consequential early decisions is whether to hire someone as a commander or discard the card. Having more commanders will help in battles but thin out the deck, discarding them will get them reshuffled at the end of the round and thus affect the balance of disastrous to non-disastrous cards in the deck. Some of the worst things to draw are combat modifiers because they automatically go into a modifier box and in general make an upcoming battle harder. These range from things like adding a -1 dice roll modifier (DRM) up to the dreaded “Enemy Reserves”, requiring Napoleon to succeed twice instead of once!

The missing agency here creates an interesting tension where the player actually will often want the draw phase to end before more penalties pile up. How many cards the player draws is dictated by the card draw track: after the minimum of 5, the player rolls the D10 for every further step and if the value is within the printed range, the phase is complete. As a result, a turn can be over in a quick five cards or last an eternity of 12 cards! Especially in the emperor phase where the upcoming campaign is already set before a round starts, the card draw phase amounts to a constant prayer for it to end an no more negative campaign modifiers to be drawn.

Europe at War

Next up is combat, or rather the campaign phase. While smaller battles called expeditions might occur as a result of a card draw, there is usually one big campaign happening per round. During the initial commander phase, Napoleon has no choice and campaigns are triggered by randomly drawing them as part of the card phase. There can be phases of quiet and then one battle follows the next. As consul, campaigns are optional and it is up to Napoleon – or rather the player – to decide which is worth the risk and which not. Napoleon needs glory to survive and sometimes going into conflict can prevent worse things to happen later. In other situations, ending up in the wrong campaign against a powerful enemy can mean the end of the game. Finally as emperor, campaigns are automatically selected based on the diplomatic relations France has with the other nations (more on that later).

Combat itself is rather simple: there are no units and everything is decided with a single modified die roll. Campaign modifiers that were drawn in the card phase typically represent special abilities of enemy forces and make things harder where using one’s own commanders makes things easier. However, to employ a commander, one is limited by the points of administration available that turn as most of them require -1A for +1 DRM to activate. Some especially powerful ones even want to be payed in glory, something that can bring the player dangerously close to losing the game due to running out of glory.

In the end, the die roll decides victory, defeat, or if a stalemate causes the campaign to go into another round of battling. Unfortunately, each commander can only be used for a single round of combat. So running into a stalemate can mean that one suddenly faces the same enemy again but now without any positive die roll modifiers! Better bring some spare commanders as reserve, otherwise things only go downhill from here. Stalemates also have the nasty effect that they cost -2G, and ending up in 2-3 stalemates in a row can cause one to run out of glory and actually lose the game.

The reward for victory or penalty for defeat depends on the campaign card and often is glory and/or new treaties that keep a country at bay. Results can be drastically different depending on which war was fought, from having to do an immediate second campaign or losing the game upon defeat to simply losing or gaining a few points of glory. If you’re in luck, you might actually even obtain the Rosetta Stone while being busy in Egypt.

Diplomacy is King

The campaign phase is followed by a diplomacy phase. Diplomacy in I, Napoleon is also kept rather simple and abstract. Each nation has a marker and track in the middle of the board and can range from ally to neutral to hostile, or in some situations even conquered. Strangely, relationships improve via conflicts (as these often end in treaties) and they get worse in the diplomacy phase. For each nation, a modified die roll decides whether relations stay the same or go down hill and diplomacy (D) points can be spent to influence results … though one rarely has more than 1-2 points to spent here. There is no way to improve foreign relations via diplomacy, which is an unusual choice mechanically. The player may even decide to end treaties because it is opportune for them to go into battle and eliminate a potential threat. But best make sure you can win a fight before you pick one.

Diplomatic relations become especially important in the emperor era as they dictate which campaign has to be fought. A set of potential campaigns is set aside during setup of the emperor era and each has a condition when it is activated. E.g. if Russia and Austria are hostile, that causes one particular campaign while if Prussia alone is hostile, that tiggers another. Napoleon can try to keep the peace by establishing treaties and then doing well in the diplomacy phase, but more often than not, something will be cooking in Europe. Especially towards the end of the game, the country boxes will have more and more cards in them that make it hard to actually maintain diplomatic relations. Well, one can’t be emperor without making enemies …

Politics, Politics, Damn Politics

Napoleon’s domestic issues are even more abstracted than those of diplomacy. Again, a single die roll decides how much glory is lost with various factors playing into it. Again, there are no upsides, just figuring out how badly you get hit. This is also where the currency Politics (P) can be spent to make things easier. Mechanically speaking, the Domestic phase is the main game element that forces Napoleon to keep gaining glory or die, as a high die roll result is needed to not lose any glory at all. On the other end of the spectrum, a bad die roll can cost as much as -10G in one swoop, which is a lot! Add to that various other negative glory income factors and you can imagine: the pressure is on.

Flow vs Agency

And that’s the core game loop for you: take income, update deck, draw cards to seed events/characters throughout Europe and get a random assortment of negative campaign modifiers, claim military victory to gain glory, use diplomacy to keep conflicts manageable, and use politics to reduce the drain of glory. While all the sorting, adding, and removing cards might seem like a lot of admin at first, after a few plays – as practice sets in – it is reduced to a very manageable task that doesn’t break the game’s flow too much.

In a number of ways, playing I, Napoleon reminded me of playing the old iOS app “Reigns” in which one governs a country just by swiping left or right on decisions. The high number of mandatory cards or cards that have easy decisions to make lets players blast through the card draw phase once they got familiar with the card deck. My very first play took much longer than my recent ones, simply because I had to double check on rules, couldn’t yet judge if I should spent any effort into getting a legitimate son or not, etc. Now, for the vast majority of cards I immediately know what my decision will be upon seeing them and the most impactful decision of the card draw phase will be what card to skip. There is a special counter called “Napoleon’s luck” that can be used once per round to re-roll a die roll, skip a mandatory card, or activate a commander/strategy for free. And this little piece of cardboard works overtime in this game. So far it has saved me from assassination attempts, being blown up in an explosion, losing a decisive battle, and much more. In a game where a lot is often decided by a random die roll, it is a rare lifebuoy on which to cling to.

If flow is so high, the obvious question is of course how much agency the player actually has and how much the game plays itself? That is quite hard to answer because it depends on whether one wants to judge I, Napoleon purely as a game or as an experience. It also changes throughout the different phases of the game. I have come to see the commander phase almost like a sort of prelude, something that mainly is there to randomise and set up the board state for the main part of the game. During CMD, the biggest decisions to make are how many commanders to recruiting and how many to leave in the deck plus when to use the luck counter. There are no diplomatic or domestic phases yet and campaigns come up at random via card draws. There are only 1-2 points of administration to spent, so the decision space overall is rather limited for this first hour of play.

FCD on the other hand is a rather short but crucial transitional phase, the first time where the game is really on the line. Sure, I’ve died during CMD, usually by not paying attention or really bad luck. FCD is where one can start to actively compensate for negative factors, but has rather small margins of error. It is also where one has more liberty to choose which conflicts to pursue and the player has to balance gaining glory or a new treaty with the risks of going to war and losing. Finally during EMD, there is an additional level of indirection. One has to manipulate diplomacy to cause or prevent certain campaigns, but usually one will end up in some campaign more times than not. The question is rather in which one.

Finally, a very nice touch is that the last few years of Napoleon’s life get subtly harder and harder as there will be less opportunity to acquire new glory and people we have gotten used to will leave the game. So one needs to grab glory and help while in one’s prime to be able to spent it towards the end. I really liked that part ones I realised it was happening.

Overall, I would say yes, there is agency there, the game doesn’t “play itself”. But it is less in the playing of individual cards as one might expect but more in the decision what to spent luck on, which and how many commanders to employ in battle, when to switch into FCD, and what treaty to break or spent the rare few diplomacy points on in an attempt to preserve it. Wife or not, assigning a king or not, these are all just colours to paint the scene. I, Napoleon should not be judged on the initial hour of playing through the commander phase but instead rather by what it ends up being during the emperor phase.

Speaking of which: the game comes with an alternate scenario of immediately jumping into the emperor phase of the game. I tried it once so far and actually liked it, although it is a bit fiddly to set up (finding the specific cards that are in and out of play). Of course a lot of the theming is lost as previous events never happened, but what it does is basically give the player a snapshot of what an average to poor CMD+FCD phase could have resulted in and immediately starts the player off with the full range of mechanisms. If I play those phases myself, I usually end up with more glory and an overall better setup, but hey, nothing to say against having a little bit of an extra challenge. I kind of wished there would be more scenarios like this included that immediately launched you into the “full game” with various international situations set up.

Conclusion

Not to stress the analogy, but similar to a mobile app, I, Napoleon got me quite addicted. It happened to me 2-3 times that I had set up another game on my table, only to pack it away again and get I, Napoleon out instead. The high level of flow and not having to think too much is actually a benefit in this case, as compared to more mid-to-heavy Euro games like my recent plays of Pampero that are a bit draining or Volko Ruhnke’s Nevsky, which I’m eager to dive into for weeks now but still dreading to learn the lengthy rules. With its play time of 1-4h (depending mostly on how quickly you lose and how much you enjoy thinking things through), I, Napoleon is meaty enough to justify making a nice big cup of tea and really getting lost in its world, but it is still stress-free and enjoyable. If it wouldn’t clash so much with its theme and all the underlying suffering and loss of life, I would almost dare to call it a “cozy” game. It’s like reading a good crime novel: might not be the most sophisticated writing in the world, but you sure know you’ll have a great evening nonetheless. For the considerable price though, one must be aware that this is definitely a lighter game than most would expect.

There is lots to like here: the cards look great and nicely convey the era, the rules are approachable and while there are lots of things to get wrong, its not an overly complex game once you get the hang of it. With the help of a few ziplock bags (not included), I can now set it up rather quickly and blast through the first couple of turns of the commander era in no time. While it’s more a two-sittings experience, it definitely has a “just one more turn” quality to it and it’s interesting to see how events around you will unfold. Side note: sleeves are definitely recommended to ease the constant shuffling, though you’ll either have to toss the insert or put cards underneath it to make everything somewhat fit back into the box.

Compared to for examples a Votes for Women or Shores of Tripolis, the mix of which events come up and which never do seemed to have more of an impact in I, Napoleon. In those two games, it never seemed to be about IF something happened but just WHEN and for how long it lasted. Here though, Spain may never rise and stay an ally until the end of the game or it can become hostile and a whole new level of trouble brews up. Napoleon might get arrested or not, bring peace over Europe or not, and so on. Don’t get me wrong, it’s not as hugely different a set of circumstances from game to game as you might hope for and the narrative and gameplay is very much on rails, but there is more in here to actually tell a new story after each play.

For reasons that are beyond me, GMT still manages to make learning the game more difficult than needs be and ignores learnings that were made in the mass market years or even decades ago. While it comes with a separate “playbook” that guides players through the commander era before throwing them into the full rules set, one has to jump between both booklets to properly set up the game, a few key sentences are missing from the playbook’s instructions, and it expects you to know how certain counters look while it gives you setup instructions. I had the exact same issues with Mr President. A brief overview of the topic is buried in the back of the playbook, and – in a first for me – the flavour text is actually NOT printed on the cards themselves but also in the back of the playbook. Thankfully the designer has added an extensive list of recommended reading material.

Speaking of which, in general, I, Napoleon very much feels like fan service and that it expects the player to already know the life of Napoleon intimately. There are key cards like “Brumaire” (marking the turn into the first consul era) or characters that appear with what I feel like is a knowing wink from the designer, but to the uninitiated blast by as purely mechanical elements that sometimes don’t quite make sense. I actually started reading through wikipedia and ordered one of the books from the suggested reading list because I was wondering why the heck a certain character would give me a positive DRM on a single event and then be gone immediately. The card flavour texts in the playbook are unfortunately rather short and I would have loved to see them being 3x longer at least. Just playing the game, I wouldn’t have had any clue about the coup that actually happened or other very interesting and important aspects of Napoleon’s life.

I, Napoleon’s biggest issue is how hard it is to keep an overview and not make a mistake. There can often be 3-4 different cards in a single box, all of them having unique impact on other parts of the board/game. E.g. Sir John Moore in the Britain box causes Portugal expedition to auto fail, which I always find hard to remember. One can spent one currency to convert it into another during the diplomacy and domestic phase, but that is not printed on the board, etc. A BGG user has already suggested to add more chits to a second printing to not only mark income but also those cards that might affect political or combat roles, but I’m not sure if this will not just further increase the clutter on the board. In general, I see a lot of potential for small usability improvements on the board and cards that will have a big impact. Until then, I strongly recommend checking out the official FAQ on GMT’s website and the list of frequently misplayed rules I posted on BGG.

There are also some minor annoyances like the board folds “wrong” and has the main gap where the card draw marker is constantly moved, so I always have to lift it up when moving from 5 to 6 (I seriously hope nobody intentionally thought this was a good idea as a reminder on when to start rolling the die). Then there is only having the removal-triggering card number printed in the bottom right corner instead of number and name and would it really have hurt to put a small marker on the year track to indicate there might be cards in the draw deck that need removal during that year?

In a lot of aspects, I, Napoleon feels to me like a version 1.0 of a new system: it is good, it shows great potential, but there are still a few bugs to iron out. Similar to the very first choose-your-own-adventure books, all the essential elements are already there but it will take a couple of iterations to really make the system shine. I think the combat is done remarkably well for such a heavy reduction of a complex topic, but neither the diplomacy nor domestic phase really felt like their real world counter parts. I would have loved to have more agency there and in the card phase, for example to have political enemies show up within France and me having the ability to counteract them. Or actually being able to do something positive in the diplomatic phase instead of just preventing decline. Overall, the board feels weird as there is nothing you can do to affect most of the cards. In some sense, that might be accurate as one can’t just make Nelson disappear for example. However, it’s a shame one can’t really formulate a strategy or plan but always has to go with the flow on what cards come up. There are rails in this game and the player can never steer too far away from history it seems.

Mechanically, I could go on for a while and pick this game apart, but that’s beside the point here. I, Napoleon is as much a game as an experience. As purely a game, it’s ridiculous that there is actually a card that comes up and basically asks you if you want to lose the game. Or Beethoven and Goethe randomly showing up and costing you glory. A good amount of things are up to chance and the degree to which you will be able to compensate for it with your decisions will always be limited. But it’s not to the absurd degree of a Halls of Hegra. As in life, sometimes shit just happens and it’s over. You need to be okay to spent 1-2 hours and then things abruptly coming to an inglorious end before you knew it. Playing I, Napoleon is as much about the journey as the ending, probably more so.

I have died, been captured, brought peace to Europe, conquered Austria, run out of glory, married and re-married, and sometimes not even made it out of the commander phase. But most importantly, I always had a good time because I got an interesting story out of it. If you’re okay with the amount of randomness and limited agency in I, Napoleon, I would say you’ll get 5-10 plays out of it where you will have novel things happening to you every time. After that, it’s that cozy novel you get out and re-read from time to time although you already know all the plot points. Personally, I think it will actually stay with me, which might be surprising to those that know my other texts. I have a very quick turnaround on games I don’t like and even for those I do, I have gotten pretty ruthless when it comes to culling (I’m still sorry, Lisboa!). I believe at this point I have already explored most of the depth of decisions that I, Napoleon may hold, but it has such a nice, unobtrusive flow to it that I can easily see myself returning to it from time to time when I’m not in the mood for a more thinky Euro or longer story-driven game like Sleeping Gods. I’m also looking forward to sharing my copy with friends and hearing what their journeys with the game will be like. I expect this one to appear on quite a number of “best solo games of 2024” lists.

Overall, a somewhat pricy but very good first entry in what hopefully becomes a new series. Ted has already indicated he is working on another title and I hope he will manage to squeeze in a few more elements of agency without raising the complexity or playtime. Or have elements that actually move on the board, that would be awesome. I see this system work best for historical characters of general renown that people are curious about to learn more, like Elizabeth, Ghandi, or Charlemagne, less so for more controversial or recent figures. And I think it’s the most interesting when discussing questions of to what degree a leader wanted to do something or “had” to do something. There are many situations in I, Napoleon where even the mighty Napoleon is just a leaf in the wind and only time tells what comes out of it. For now, I’ll be waiting for that Bonaparte biography I ordered to arrive and am very much looking forward to further plays and the next entry in the series.

Thanks for your impressions. I’m learning the game (currently into FCD) and enjoyed your report. Will print the ‘easy to forget rules’ to aid my learning curve. Well done.

Thanks, glad you like it! You might find the list of frequently misplayed rules I posted on BGG helpful while starting out: https://boardgamegeek.com/thread/3350210/frequently-misplayed-rules