Euro games are a tricky category to design in. While their focus on balanced game play and avoidances of direct player conflict has given them immense popularity over the years, those strong points have also caused a lot of new releases to feel bland and interchangeable. Why should one care if one is building churches throughout Europe, curing patients from their traumas, or even building a civilisation when in the end it’s all just symbols and points?

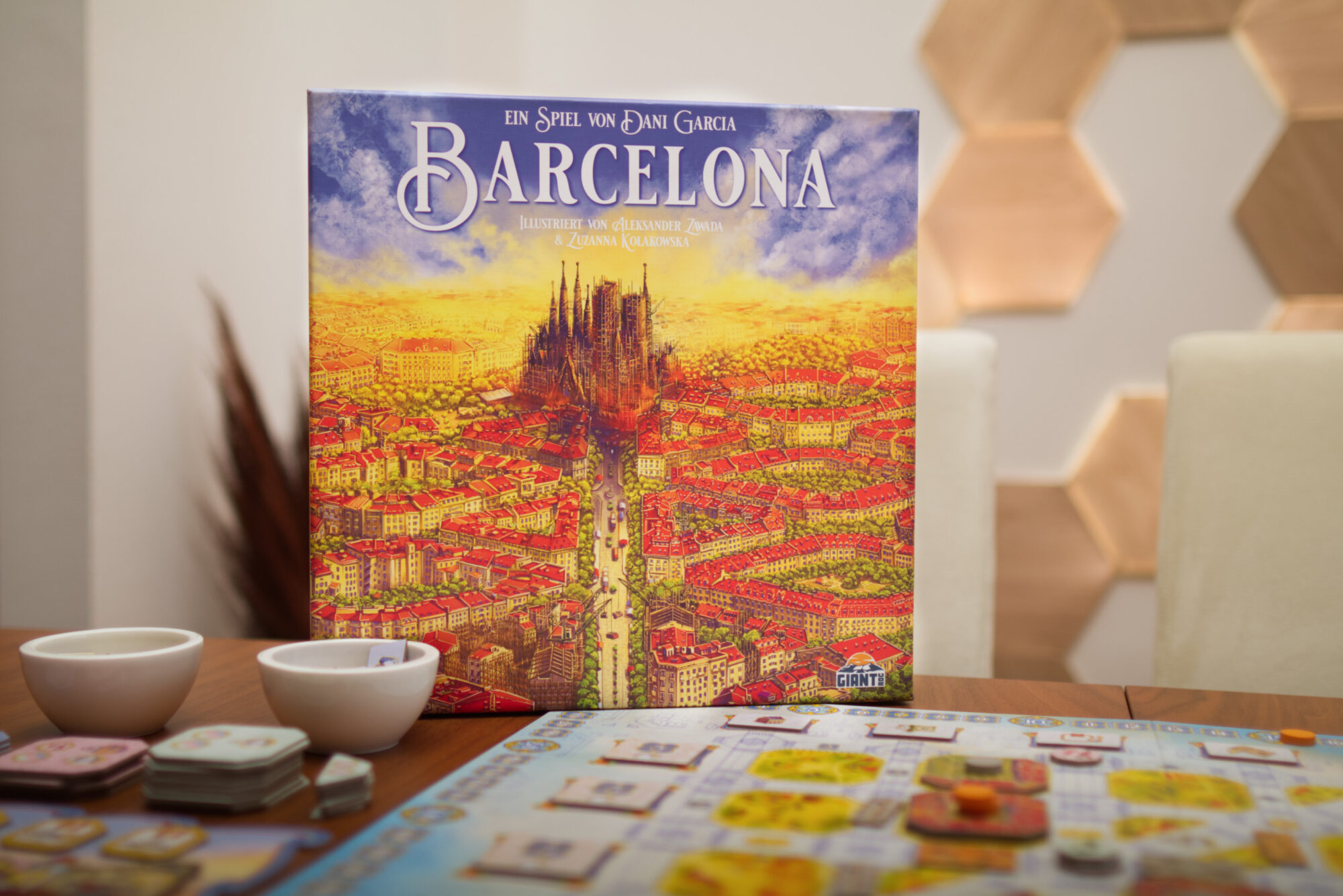

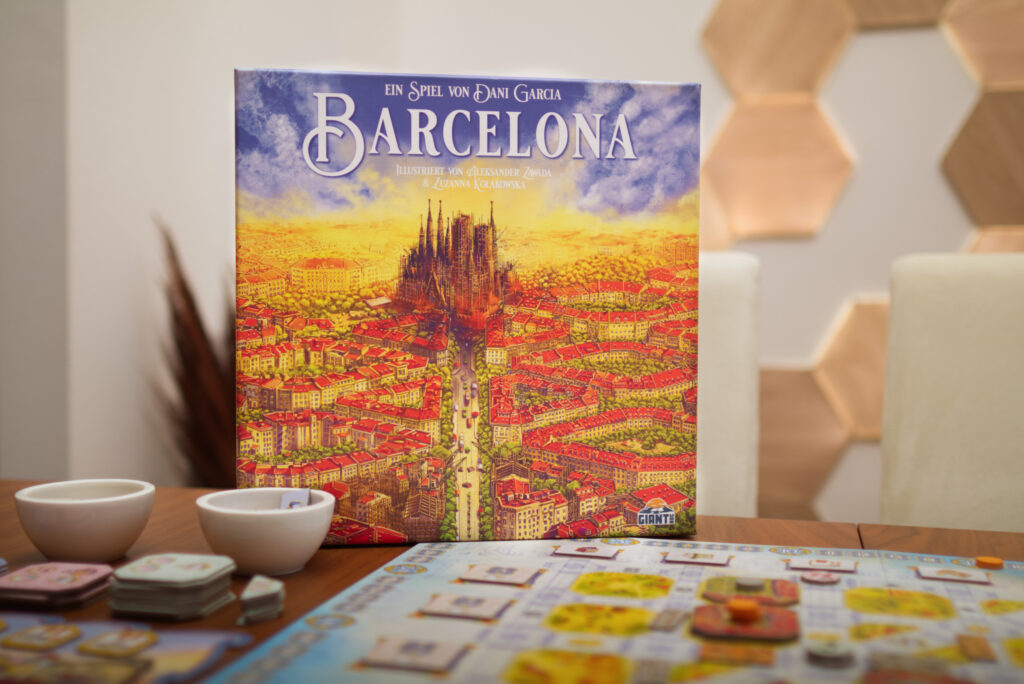

In a sea of forgettable Euros, Barcelona managed to bring back the charm that made Euro games like Grand Austria Hotel such classics. Sure, it’s a combotastic point salad where scores of upwards of 300 VP are possible, but it brought something unique to the table with it’s action selection mechanism and positional play, combos that felt good but not overburdening, and most important for me had a theme that isn’t just a thin coat of paint. I sat down with Barcelona’s designer Dani Garcia – who suddenly and seemingly out of nowhere rose to fame in 2023 on the strength of Arboria and Barcelona – to get a feeling for what he might have done different than a lot of other designers and why I care about this Euro when I don’t for so many others.

In this part, we talked about beginnings, both of Barcelona the board game as well as Dani himself as a designer, and various design choices he had to make. In part 2 we continued with his approach to playtesting, the reception when Barcelona was finally released, and of course we dive into the newly released expansion Passeig de Gràcia.

Early Beginnings

Going back in time, what is your very first memory of Barcelona?

I think it was in 2020 for sure. I live here – not only in Barcelona but in the part [of the city] that the game talks about. So every time I went on the street I saw this grid of streets and for a designer a grid is something that’s very easy to convert into some part of a game. I think it was the coincidence of that: the fact that I was just walking on the streets as usual plus there was a documentary on television about Cerda and the creation of the Eixample, which is something that [if you go to school in Barcelona] you are always taught and I remembered. I already knew a lot of that, but that documentary … I guess it brought back memories. It was this combination between having seen that recently plus being walking on the streets that I said “okay, I could probably do a game about this“. I immediately imagined the grid of the streets and that you had to place citizens on them and do something.

When you say walking on the streets, what were you doing?

Everyday life. I would just bring my kid to school, go to a shop, or whatever because I’m just in the middle of it. In fact, I had to reduce the map of the game a bit, but my house was [originally] in the map! [Dani smiles, Alex laughs] It’s not just a random grid, it’s a specific part of Barcelona.

Not everybody walks around the street and says, okay, let’s create a board game. Was it your first design or were you already creating board games?

No, I think I’ve always been interested in designing games. I remember when I was a kid – I’m not sure, 10, 12 or something like that – I remember asking my grandfather (who was good at drawing) to do some drawings of some military units. I was basically copying a game that was set in a medieval setting and just converting it to modern era warfare. When I was 18, I tried to do a role-playing game with a friend. So I had these moments in life where I was designing things just for fun, just for me, and then some other moments where I was not doing anything. I think it was around 2019 that I recovered one of my old designs and I thought: okay, this one is good. I think this one can be published.

I was wrong! [both laugh hard] But at least it put me in the mood of “okay, I really want to try to publish this one and I will try to contact a publisher and properly do it”. In 2020, I decided “okay, let’s really try it”. [At the time,] I had a small video game company that I had to close and I said, now is the time! There’s no better moment to try it, so I will work full time on this and see what happens. I think Barcelona was probably my fourth or fifth design of that year because I was trying to not stay with the same design too much, [instead] trying to do something, see if it works, and if it doesn’t work, you have learned something and you go to the next one. So yeah, it wasn’t the first one. I was already in the mood of finding themes and finding mechanisms. I think that probably helped a lot.

I was just wondering because before 2023, most people hadn’t even heard of you.

Yeah, because I was invisible. [Dani laughs] Some publishers already knew me because Arboria’s Kickstarter had launched, which was my first appearance anywhere. I think I had already signed five games and I knew that some testers and publishers – because they are all the same designers, testers, publishers, we all know each other – they were already talking about me and telling other publishers “maybe you should check the designs of this guy”. If I’m not wrong, Daitoshi was a commission from Devir and it happened before Arboria appeared. So they already knew me and they wanted to work with me.

Oh really?

Yeah, I was unknown for the public but I had already been working for three years non-stop. That was when I think people were starting to notice me in the inner circles.

From the outside, you suddenly were there [Dani laughs] with two games and people were excited to see more games from you. You almost overnight became a household name where people said: Dani Garcia has a new game? I want to check it out!

Yeah. It happened really quick. I couldn’t have dreamed it to be better to be honest. Probably Rahdo helped a lot because he – I’m not sure if with Arboria but with Barcelona – he started saying I was one of his three favourite designers. I think that helped a lot. And well, they were big games and they were from companies that were big enough so that they had some repercussions. I guess if you start with small games with a small publisher it’s harder for you to be noticed. But two years on the same game with big publishers I think that helps a lot. And I hope also because the games are good.

Was Barcelona something special for you because you live in the city?

Yeah, absolutely. In fact there are some games where I won’t say that I don’t mind if they change my theme. But for Barcelona for example, I would not have allowed it. Board & Dice never proposed it because they understood that it had to be about Barcelona. But yeah, it was really rooted in the theme and the history of what happened. And obviously, I’ve always lived here, so it was a special project for me. I really wanted it to work and to keep the essence and the history that I tried to investigate because I also did some research. I knew most of it, but I tried to do research to make it as accurate as possible, knowing that it’s a game and you have to make concessions. But yeah, I put a lot of effort there. So yeah, it was really special.

I remember when Barcelona came out and I first played it, it had something different. I had played so many Euros which were almost interchangeable for me and then Barcelona seemed to be the first one in a while where it wasn’t just inspired by a theme, but it actually felt thematic. Do you have a theory why Barcelona feels thematic even though it is a Euro?

Well, depending on who you ask, they won’t agree. [both laugh] I’ve also seen people think that it’s not thematic and it could be any other city. But obviously I don’t think that’s true. I think when you’re playing the game, if you only want to focus on the mechanisms, you will focus on that and that’s all. And yeah, you could say because it’s a city, you can place any label on it and it will work. But if you know the history or even if you read the history bits that I added in the rule book, it can only be this city. Starting with the shape of the buildings, there’s no other city, not only that it’s a grid but it has those octagonal shapes. And the fact that Cerdà wanted only two sides of each block to be built. And that’s why if you build more, you make him angry, if you build less, he rewards you. And there are a lot of elements where the combination of all the elements only happened there. I imagine it’s this that makes some people really feel the theme, other people won’t care and they will ignore it. But at least for the people that really care about this, I wanted it to be obvious or to be noticeable.

I have to thank Board & Decide that they kept all those thematic bits in the rulebook. Because they have no game purpose, they could have just removed them but they kept them and I think I’ve seen a lot of people saying they were happy that they were there because they were learning something. So I imagine it’s a combination of everything. The fact that it’s really about that city and that there’s the history that you can read and make the connection when you play it.

So you wrote the historical notes in the rules yourself?

Yeah, [Board & Dice] did corrections because I’m not native English but yeah, the gist of everything I did write.

I was asking because I was talking to Thomas Holek at SPIEL. I feel you’re a bit related as designers because you’re both very passionate about your topics and you both managed to bring more theme into Euros than a lot of other designers. With him, it seemed to be like he was so passionate about his projects that he had no other way than injecting as much theme as he could because he was always thinking about astronomy and so on. Perhaps it was similar with you? Were you thinking so much about Barcelona and all the background that you tried to push everything into Barcelona the game?

I guess it may be the same for him: At the beginning I was more of a mechanics guy, let’s say. I was focusing on the mechanics and trying to make everything work. But I’ve done a transformation and now I’m just on the opposite side. If you ask me to just do a game, just make some mechanics, nothing comes to my mind. I use the theme to generate ideas about the mechanics. […]

There are other games where I also need the theme in order to create the mechanics. But maybe then if I show it to a publisher and they say, OK, we like it, but we have to change the theme, will say, OK, fine. But there are some others. Now I’m working on another one that it’s like Barcelona. It’s about something that’s close to me, and I wanted to keep that theme. So in this case, it’s not only that I also did the same study and the same research before doing the mechanisms. But now if I go to a publisher and they say, OK, we want to change it, I will say no. This game has to be about this and if you don’t agree I will try to find somewhere else to do it. I’m in a position now where I can say that because four years ago I would not have said that. But yeah, some games are more special at least on the theme part, the thematic part. And even if it’s common that publishers may change the theme in a few of them I want them to keep it.

Designing The Game

What did your first prototype look like?

Well, it wasn’t working, that’s for sure. I had the grid of Barcelona and I think I already had the idea of placing citizens. I think it was just one, not a stack of two there. But the game was the opposite: on the edges you didn’t have actions, you had resources. So basically my idea was this will be a game with 10-11 resources, a lot of them, and you will have to collect them and then do actions with them. You placed the worker, you got the resources and then if you could build – because you had to pay a certain combination of resources to build on different blocks – you would then not only build but do the action of that block. So that was the action selection system, to build there. But yeah, it just wasn’t working because you took many turns to just take resources and did nothing else. So it was not fun.

Also the citizen track: It was there but it was working completely different. I don’t remember it exactly but when you build I think you took the citizen and place it on the track and then you got a reward depending on which position you were placing it or you unlocked powers or … I don’t remember exactly. But it was like the key elements and most of the actions were there, but they were [arranged] in a completely different way and the game was just not fun at that stage. But it’s normal on your first prototype. It’s a miracle if it more or less works.

Give me a sense of the timing. How long did it take it for you to start with this first prototype and then up to the finished game?

I think I started by the end of 2020, would say probably November. And I probably had to not finished because then you go to the publisher and they change things. So it was not the final version, but it was only five or six months.

Oh really?

Yeah. Nowadays I have to overlap them because I’m working on so many things,. So if I tell you it took me six months to do this game, it means that I was doing this six months period, but I wasn’t working on it full time because I was doing many other things. At that time, I was more focused, so maybe it wasn’t six, it was five, but I was probably more focused on only this project. By that time, I didn’t have games that were releasing and [jokingly] now I have to do the solo mode of this game and …

And that’s even including play testing and balancing?

Yeah, usually I have the idea in my head, then I create the prototype, I try it myself. Usually it doesn’t work, I have to do several versions of it. But I try to do that as fast as possible. And as soon as I have something that more or less can be played, then I immediately go to testing. And that time was good because … well, it was good, it was the pandemic. [said in a tone that emphasises the irony of it being really good for playtesting but of course not good in general terms]. That also meant that everybody, all the designers, were on TTS and Discord. So every night you didn’t even need to book people. You just showed up during the night and said “who’s available to test?”. And so you could pretty much test every night that you needed a test. So it was really quick to progress.

It sounded very fast. I always imagined that the balancing of a good Euro takes like ages.

[In the beginning,] I was trying to get it completely balanced and then send it to publishers. Now I know the publishers will want to change things and will have their feedback and so it doesn’t make sense to have it completely done. So now what I’ll do is I playtest it until it’s good, it’s playable, but it’s not balanced. Maybe there’s things that are completely broken. You can play the game, but now there’s this card that does this thing that you can simply win with it. It’s fine. I try to balance it as much as possible, but as soon as the game is playable and the idea of the game can be shown and you can play a full game, I try to send them to a publisher. And then, of course, there’s this process of maybe they will give you feedback and you make changes, or maybe they will take it, some changes, show it to you, or that depends on the publisher.

So there’s a lot more testing that has to go on and there’s a lot more time that you will spend. But it’s not really doing the game. At some point, it’s balancing and I consider that to be something different in the process of creating a game.

One thing I really like about Barcelona is that it’s not only placing the citizen to select your actions, but you have this side game, this positional power play that I try to play citizen in a way that I have a good action but also that I prevent my opponent from being able to build a building if possible. Was that part of the initial idea or did that come later?

Yeah, I think so. You were placing a citizen and then removing them and placing them on the sideboard same as now. Now the final idea, I think it’s more thematic because you are not just removing citizens just because it’s that they want to find somewhere to live and they are going to that building. I’m not sure if I had that thematic connection at that point maybe I had but I don’t remember. But yeah, I knew that it’s basically a worker placement game, so you need the way to remove the worker from the spots or otherwise they will be blocking all the game. And I didn’t want to have a “recover workers” phase because they are not yours anyway. So it’s not like we’ll be all placing our three workers and then we recover them.

So I don’t remember exactly when, but from very early on, this was part of the process. When you build, you remove the citizens that were going to live on that block. And this was the way to free a spot. I remember that I was only placing one citizen on each crossing in the starting version. And I guess that was removing the citizens too fast and it was not possible to build and it was too easy to find the correct spot. That’s when at some point I decided to have these two citizens in a stack so that they stay more on the spot and they give more building opportunities, but they also block the spot for longer. And yeah, it creates this interesting situation where you’re not only worried about the actions you are doing, but you’re also worried about trying to build yourself. And you’re also worried about, if I play here, will the next player be able to build with my workers or not?

At the end of the day, we want games – or at least I like this kind of games – that they push you in different directions, because I find them more interesting. And this was a good way to have this layer of decisions on just the simple act of placing a worker on one spot.

What was your thinking on the combos? In Barcelona, you have two (sometimes three) actions, so there’s already a “do I first do action A or B?”. But then it’s also like “okay, I use my action to place a cobblestone to get this, to do this, to do this”. Do you have a philosophy when it comes to combos, like how big or how small they should be, how long they should take or something like that?

Yeah, it didn’t happen with Barcelona, with the next one I designed – Windmill Valley – I remember that I took notes and after one playtest it was: [jokingly] too many combos.

I like them, but at some point they are too many. It’s not that I have a rule, it’s just a [result] of testing them I guess. So if you see that turns are taking way too long, it’s fun for the player that’s doing the combos but for the other three players it might not be as fun. So I try to make them possible as much as possible up to a point. There has to be somewhere where the combo has to stop because there’s no other ways to do other things.

So for example, in Barcelona you have either two or three actions depending on where you place your worker. And then there’s a few actions that let you combo, but not that many. You have the cobblestones that you can place streets with, but if you place streets, that’s it. There’s nothing else that you get from placing streets. Or you can get modernism tiles or upgrade them. But again, if you do that, that’s the end of the combo. There’s no more. There isn’t anything else there.

You have the public buildings which themselves are very simple. I just spend three coins, I get points and increase on the Cerdà track and then I do the action. It’s basically a combo but it’s just like a small step behind the proper action that you want to do. And then you have the tram, that yeah, it’s pretty much the same. It’s an action where you have to spend something in order to place a passenger and then do the action that you were planning to do.

Obviously you can combo several of them at the same time: I move the tram to do a public service and then the public service gives me the cobblestone and then I do streets. But that only will happen once or twice during the game and most of them will be under control. These kind of combos, they are good in order to make actions available when they will not be. So for example, I want to build here but I want to do that action and they are not on the same spot but I can do the tram action and then move to the action I really want to do. So for me, it’s also, it’s not only that you feel really clever and really good when you perform them, but it’s also a way to give players more options and give ways to do the actions that they really want so that they don’t feel blocked.

Is that something you notice that is particularly rewarding if people find like a way around the limitation?

Yeah, absolutely. Obviously there will be people that don’t like it because they are not good at finding that path and then it’s frustrating. But for me – and I know for many other players – the game is giving you these simple options and if you do those simple options, will perform, you will do some points and you will do some actions. But if you can see a way around it and see, okay, I want to do this action but is there any way I can do this action by doing another action? And then if you have found that, is there a way that I could undo the second action with the third action?

You have examples of that. One of the last games of Vital Lacerda was a lot like that. For Inventions, that was the core idea – I think – of the game. If I want to do this action, OK, but I can do it with the second action and the second I can do with the third action. And the point of the game was to do as many combos as possible. Yeah, I think for some kind of people, including myself, it’s really rewarding. But again, at some point it can be too confusing or just too much or it takes too much time to resolve everything. So you have to make sure that they will stop at some point.

Inventions also immediately came to my mind. You try to put so many chaining things one after another! Sometimes I had a very clever plan and when I came to the end of my chain, I forgot why I started it.

Yeah, yeah. [both laugh] That’s probably on the edge of that moment of there are too many combos and I lost track even myself of what I was doing. But obviously Lacerda games are for heavy gamers. So it’s okay for them to be that complex. In my type of games which are … lately, I’m doing Daitoshi for example. I don’t think it will stay at 4.0 but it’s now at BGG it’s at 4.0. But for example, with Windmill Valley or Barcelona, at around 3.0, you cannot have this level of complexity and chaining. You have to always, more or less, be able to think about your strategy and don’t forget it mid of your turn.

Now that you mentioned it, are you thinking about the target complexity when you design a game? So was it like, hey, Barcelona, I want this like in this mid level and Daitosihi, I want this to be more heavy?

Not exactly. I know that I like a certain range of games. And even if I try to do a simpler game, I usually find things that I can add and maybe I’m doing creating the board and [jokingly] there’s a blank space here [Alex laughs] so I can do something there because I don’t want to leave it blank. They end up inevitably, they get more complex and then by playtesting I reduce them a bit because I try to clean up things and streamline them. But yeah, I think I usually do games between I guess three and four, not because I really plan to do them, but it’s my comfort zone, it’s the type of games I like the most. And sometimes I might do something that’s a bit lower than that, sometimes I might do something that’s bit heavier than that, but I think most of them naturally end up on this spot because I do this process of making them a bit more complex than they should be and then reducing them as I polish everything. And yeah, and then obviously it depends on the publisher you send the game to. You know they have a certain range of games so [jokingly] if I were talking with Eagle Gryphon Games, I would probably be able to do much heavier things. But yeah, it’s the opposite process. I do the game, I see how it feels in terms of weight, and then I decide, OK, maybe this one might fit this publisher and I can show it to them.

Were there things in Barcelona you cut out because of where they would have made the game too complex?

Yeah. At some point I had, it was part of the things that I removed, part of the things that Borlanda removed at the end. I think most of them I removed before giving it to [Board & Dice]. The original board was six by four streets. So that’s why my house was in the map [Alex laughs] because it was on those two extra streets. Because I had another action, one related to the tram in which before moving the tram you had to invest in infrastructure. So basically building the tracks and at some point they become electric trams. The first ones were carried by animals, I think, if I’m not wrong, and then they become… So you needed more preparation to do that action. It was more complex. And there was another one that I don’t remember, but there was another action because there were two more streets. So I had to simplify that based on some feedback I got.

I also had some tiles that allowed you to do an action two times if you had got them previously. But I think that was Board & Dice that removed those because I guess they thought there were too many combos there. But yeah, think that’s the ones I remember. It was the fact of removing two streets that obviously there were two more actions and they had to be removed. So I remember the tram one, I don’t remember the other one.

Designing the Map

Let’s jump to something else: map design. I’m always fascinated how designers come up with the map they work with. You said you had the grid and the diagonal in the beginning. Did you already have the narrow and wide streets also?

I think so, yeah. Because the thing is, in this part of Barcelona, the grid, there’s two really big streets that cross it diagonally. One is called the Diagonal and the other is called Meridiana. But they don’t cross in a 45-degree angle. It’s more like 30 degrees. So that’s a problem because that meant that if I had a section of the border that had that street, some streets would not have [regular] shapes. So you will need specific pieces for each of them and some of them will be real small. So I tried to look and there’s just next to my house there’s one street that crosses completely in diagonal and in fact it connects the Sagrada Familia and Hospital de San Pau which is also a modernist building. So it was perfect for the game because you want more symmetrical things in order to make things easier. And yeah, so that’s the reason why I thought about the diagonal, I thought about the other one because it’s famous and to make some to add some variability to the game but then I found this space to make it easier to work with and then the diagonal street the real one that’s called the diagonal it’s really wide and in fact in Barcelona I think I imagine I already researched that at that point but every three or four or five streets there’s one that’s wider than usual and this was done on purpose in order to make wider avenues for the cars or in that time the carriages could move faster.

So yeah, I guess I had the idea. So the ones that I chose to be wide are not really that wide in reality because none of those cross this specific zone. But yeah, now that you say it, I think I remember that I had already researched that and I knew that I had wide and narrow streets because they were planned like that in the planning.

The other thing that’s very striking are these lovely illustrations of the buildings with the L-shape for the two sides and so on. Did you have this idea of overbuilding from the beginning?

Yeah, in fact, if you look at a map of how Cerdà wanted the city, it was everything either L shapes or the two opposite sides of a block. So it was a certain combination of that. With L shapes, you will create a big square around four blocks. And with the ones that are one next to the other, you could create like streets, but with the park in the middle. So he had this idea and he had these kind of formations. And on my first idea, I didn’t have the whole blocks. I just had the sides. So you could first build one side, then build the second side, then ideally the third, the fourth, and the middle part, which it’s more or less the process that they followed when they were being built. And I guess I also had that idea because if you look at photos of the time that it was being built, you will see a huge zone with just the streets being laid or just that they were not paved. They just had the direction of the streets, but they didn’t have stones or anything just to cover them. It was just to say, there will be a street here. And you could see that there were some blocks already being built. You will have blocks where just one side was already being built or just some houses on one side. So I wanted to create that idea of it slowly being built side by side.

But that was part of the problem. It was very fiddly. Because you had very small pieces, five of them that should be placed on the middle of a block and then the streets around and the intersection. So there were way too many small pieces on a small part of the board. And I guess this evolved into that having tiles with two, three or four sides already done and then the option to overbuild them, which basically is just building an extra side or two extra sides on the block. But because they are tiles that you have to place them on top.

But yeah, I guess it was pretty much from the beginning because this is also what happened in history. I think at the beginning they tried to keep the plan as much as possible but then the landowners knew that they would make much more money with a building than with a park so everything ended up being built.

I remember when I first taught other people the game, the immediate question was, hey if I have this L shape does it matter how I rotate it?

Yeah, in my prototype I had L shapes rotated just for visual effects and I also had the other version with the one side by side but they were lost in the process of doing the graphics which is a very small detail that I would have liked to see but yeah, it’s just completely visual. I think I thought at some point I’m doing something with them because as I said, if you see a map of the planned city, there were some structures that you would build with several blocks together, they would build a structure, but it was just too much and I decided not to try to incorporate that. This is one of those small details that’s way too much information and there’s no need to add them to the game.

Did you ever try to get the public service buildings or Sagrada Familia somehow into the map?

Well, it’s on the edge of the map, on the lower left corner of that diagonal street, that’s Sagrada Familia. And I had it in the prototype, don’t remember if I had an image or I just had the name, just in case they wanted to include it. But then obviously they had to move things around in order to do the final graphic design. And they added it on the side as a picture of the columns.

In fact, the Sagrada Familia track was not part of my prototype. The mechanism was there, but I was just calling it modernism track or something like that, because it represented durability as a modernist architect. And they pretty much kept it the same, I imagine they said that the Sagrada Familia have to be in a game about Barcelona and they converted it to that.

Okay, that explains a lot. I was always like, hey, this is such an important building. Why is it not anywhere on the map?

Yeah, yeah, I guess it’s so obvious that I wanted it to be there because it’s next to the map so it can appear there as a landmark. Because it was Gaudi that did the Sagrada Familia, well, there has been other architects but he’s the main one and you are not Gaudi, I think it felt strange to add it as, for example, a goal of the game to build the Sagrada Familia or something like that.

The other surprise I still remember when I was unboxing the game was finding this victory point chip. First like 100, 200 and I was like, okay, that sounds ambitious. And then I found one with 300 and 400 and I was like, my God, what is this game doing? Was it intentional that there are so many victory points in this game?

That’s something I’m now controlling more. [both laugh] I think part of the reason is that I like to multiply things. There are some jokes about that already, that if the is a game of mine without multiplication, it is not mine. And yeah, when you start multiplying things, obviously things start really quickly. And you want to have … If this is the easiest thing or the lowest thing that will give you points, and this is one point, and that thing is 10 times harder to do, so that has to be 10 points if you want to balance it.

So yeah, with Barcelona and Arboria I had these crazy scoring because I had multiplications and because they are very points high, so pretty much everything gives you points. Now I’m trying to keep them more under control, but I still have many games where you can reach 200, so at least I have the number. But I think it was part of the idea of the game – and my philosophy – that I want to have positive interaction and to reward players in general. If you do an action and it gives you something, some reward, if it gives you resources or points or whatever, you feel good. So maybe I was too heavy with that idea in the beginning, but yeah, it felt good and people that were playing it felt good. It’s always nice. And the good thing is that when players [are on a equal level], you can have 300 something points, but they will win with a two or three point difference. It felt really good to have these crazy numbers, but then they all end up almost close together. So I decided that, okay, then it means that it’s balanced.

One thing I have to ask you is: I managed around 360 points in one or two games. I’ve never reached 400. [jokingly] Do you think like 400 is realistic or is it just you need something on the backside on the marker?

It’s possible, but it has to be a two player game. It has to be a long two player game because it depends a lot on how the citizens appear. And if you build really quick or you spend some turns not building. So basically the more times you play, the more points you will do. So it has to be a game where you play two, three, four extra more turns than usual because of those things. And obviously if the citizens fill the tracks, the last buildings already score 20 points.

One thing I’ve found really fascinating in your designer diary was that you mentioned that you only cared about the ending once you figured out the design worked. How did you decide where you do it? Want to have the ending? Were you thinking about a certain emotional arc of the player? Were you thinking mainly of like, okay, let’s cut it so it’s like a two hour game?

Yeah, the thing is I usually don’t like games that… I like playing them, but I don’t like to games where, okay, we will play three rounds and that’s all. Or you will find games of mine that will do that, but most of them there’s some ending condition that will happen whenever you do certain number of things during the game.

So when I’m starting the game, I cannot know that because I don’t know how long the game takes, how fun it is, what you do. Sometimes I don’t even know what will be the condition. In this case, I don’t remember if I knew. So for some games I know it will be whenever this track is empty, but I don’t know how long this track has to be, for example. When you are playtesting you at some point see, okay, this is already taking too long or now turns are crazy because the engine is too big and then they start doing too many combos. That will give you a clue, also the length of the game. I try not to make them way too long. So for example, for a four-playing game, I try to be two hour stops. Obviously, if it’s your first game, it might take longer, but I try to put that as a limit.

So once the game is working and once I see how it’s going, it’s something I adjust live. Or sometimes I’m doing a playtest, I say, okay, that’s enough, let’s cut it here and then I count, okay, they did 12 turns, for example. So it should be the ideal and let’s try to make it last around 12 turns based on the ending condition I want. And then I keep adjusting it as I keep playstesting. But when I start, I have no ending condition because I’m not going to [play the game completely to its end] anyway. So there’s no point. And as the game progresses, I keep adjusting it.

This concludes part 1, part 2 should come out in a week or two.

One thing that continues to amaze me about our hobby is how nice most of the people in it are. Dani is one of the absolute shooting stars of the last two years and talking with him feels like hanging out in a bar with a good mate. We talked for just over 1 1/2 hours and probably could have kept going. Getting the conversation down to a readable size was a challenge though, so I had to drop a few minor tangents. As always, I applied some editing and clean up of phrasing to improve readability. Any mistakes are likely mine as editor and not Dani’s.

If you are interested in Dani’s work, check out my first impressions on Barcelona as well as the ones on the recently released expansion “Passeig de Gràcia”. For SPIEL Essen 2024, Dani’s new heavy weight “Daitoshi” was released and for a lighter mid-weight game, check out Windmill Valley about the historic tulip craze in the Netherlands.