To say Sleeping Gods: Distant Skies was my most anticipated game of 2023 would be true, but kind of missing the point: it was my only anticipated game of 2023! I usually don’t “anticipate” games. Sure, I’ve backed a handful of crowd funding projects I would like to play right now, like Pampero or Inventions: Evolution of Ideas. But if they would take six months longer to fulfil, I wouldn’t really mind that much. Another Sleeping Gods on the other hand, now that’s something to look forward to.

Sleeping Gods was a phenomenon when it hit fulfilment back in 2021 and since then has steadily climbed up the BGG charts. There had been other chose-your-own-adventure-style exploration games like 7th Continent before it, but the open world nature of the story created a strong sense of being able to go anywhere. While there was an over-arching storyline, it was rather loose with only a very general goal: find a sufficient number of totems – powerful objects with magical properties – to awaken the gods and thus open a way back home before time runs out. Sleeping Gods was at least as much about discovering its world as it was about the main quest itself. And with tons and tons of content in the box plus an expansion and add-ons, even eight campaigns in, I’ve roughly seen between a third and half of what can be explored.

Over the course of the year, I’ve been following the updates on GameFound, eagerly awaiting fulfilment to start. So far, my own copy hasn’t arrived yet but a very kind reader offered me to borrow their copy. And so I ventured again off into the world of Sleeping Gods …

(note: the following will avoid any spoilers regarding the story itself and discuss more the mechanisms and narrative structure, especially in comparison to the original Sleeping Gods. However, it will cover the introduction before the first exploration in broad strokes to give readers a general sense of what the story is about this time. If you want to go into Distant Skies completely cold, you should stop here and come back once you have completed the very first exploration.)

Box Content

In many ways, Distant Skies is an iteration upon Sleeping Gods, a mixture of familiar and improved. This immediately becomes obvious when opening the box. Its dimensions are exactly the same as Sleeping Gods’ and the moody green tones surrounding the ship we came to know as the Manticore have been replaced by blue skies surrounding a plane. Even the giant sea monster lurking under the surface has its equivalent in a flying dinosaur-like beast. Both boxes are packed and quite heavy with the base game of Sleeping Gods feeling only slightly heavier than Distant Skies with the Thunderstone Island expansion included.

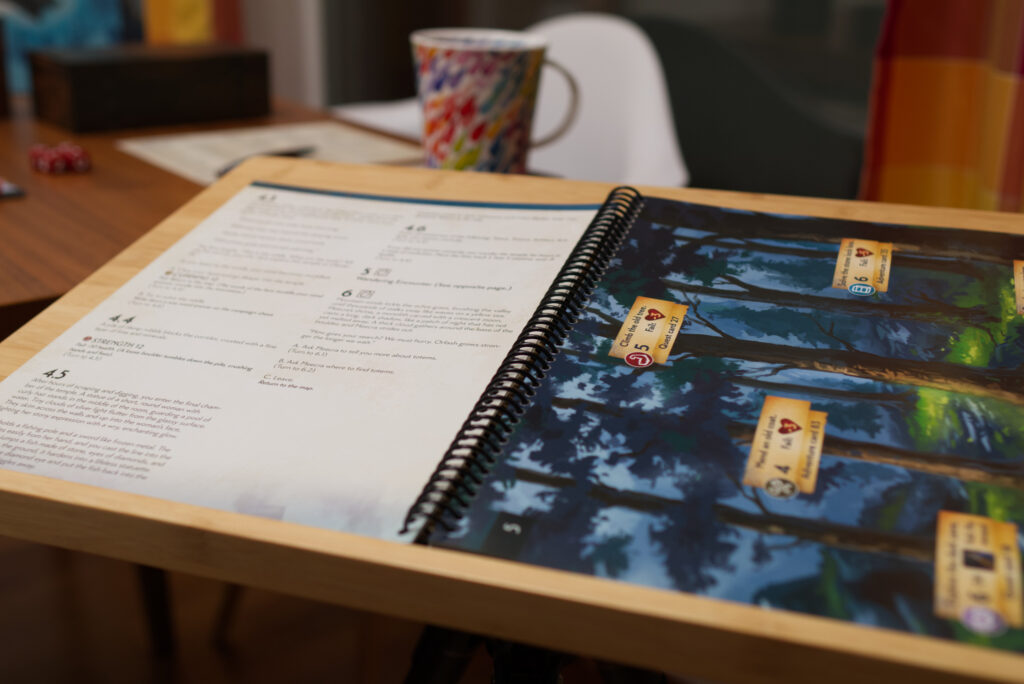

As before, there is a ring-bound atlas that acts as the map on which the players explore the world. This time it is imperceptibly enlarged (by perhaps 1cm) but two aspects become obvious quickly for those that have played the original Sleeping Gods: for one, the world looks more zoomed in. The things represented in the atlas are more in multi-day hiking distance where they were a longer boat ride away in the original. The bustling cities are replaced by smaller towns and although there are again what looks like different climate zones, everything feels closer connected.

The other difference lies in the art style as the map doesn’t feature as many small details as Sleeping Gods’ map. One of the unique aspects of Sleeping Gods was the shared experience of players looking at the map and wondering “what’s that over there? A rock? A statue of a bird? Let’s go and see!”. This happens much less in Distant Skies and players will rather follow the directions of the various characters and plot lines they will encounter. But it’s unmistakably Ryan Laukat’s painterly style similar to what he used in Sleeping Gods.

There is again a big box with a magnetic lid that houses approx 400 cards representing events, items, temporary characters, and quest lines. In fact, this is the exact same box players know from Sleeping Gods, up to the fact that I often mistake which side is the one the lid opens towards. There are also the familiar smaller-sized ability cards (which both function as random number generators for skill checks as well as unique abilities that can be equipped to characters), wooden damage tokens, cardboard resource tokens, status effect tokens, monster cards, stamina tokens, and so on. New to Distant Skies are a set of plastic minis (also included as cardboard standees) representing the characters in the party as well as some combat dice.

Same as with Sleeping Gods, each character is represented by a large board, but this time the number was reduced down to five. This is one of many reasons why Distant Skies is less of a table hog and there is less table clutter, as we’ll continue to see throughout this text. Each character again has a set of ability icons used for skill checks, some unique to them abilities, and now features also a health track. In Sleeping Gods, damage was represented by placing wooden and cardboard tokens on the character where now it’s a track. This makes sense as characters have roughly double the hit points.

There are also multiple side-boards for tracking the current location of the plane that is featured on the cover, the progress during a turn, as well as the current combat deck, all of which we’ll discuss later on.

The World

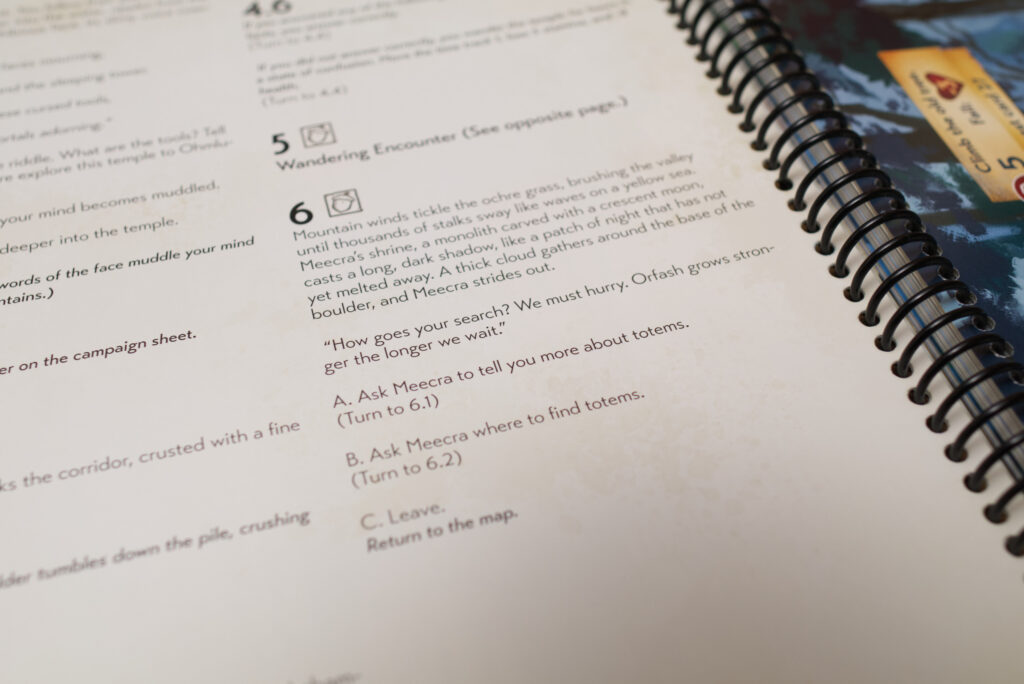

The heart of Distant Skies is again the encounter book, a collection of numbered sections that get referenced when players explore one of the locations on the map. For most locations, there are multiple possible options what can happen, depending on choices players make as well as what other quests they have explored before. Both Sleeping Gods and Distant Skies use a keyword system: each quest or important conversation leads to the players receiving a quest card, a numbered card with a short summary and a unique keyword on it. For example, the players might come to a village and there is a street bustling with life. A few quests down the line, players might re-visit the exact same location but the book says “if you have keyword SCARED, go to 134.3” which will let the players know the street is now ominously deserted as a result of what they did before. Even without keywords, a section will often ask players to make a choice and/or perform a skill check (more on those later), leading down to other sections (e.g. “if trying to convince, go to 134.5. If trying to steal, go to 134.2”).

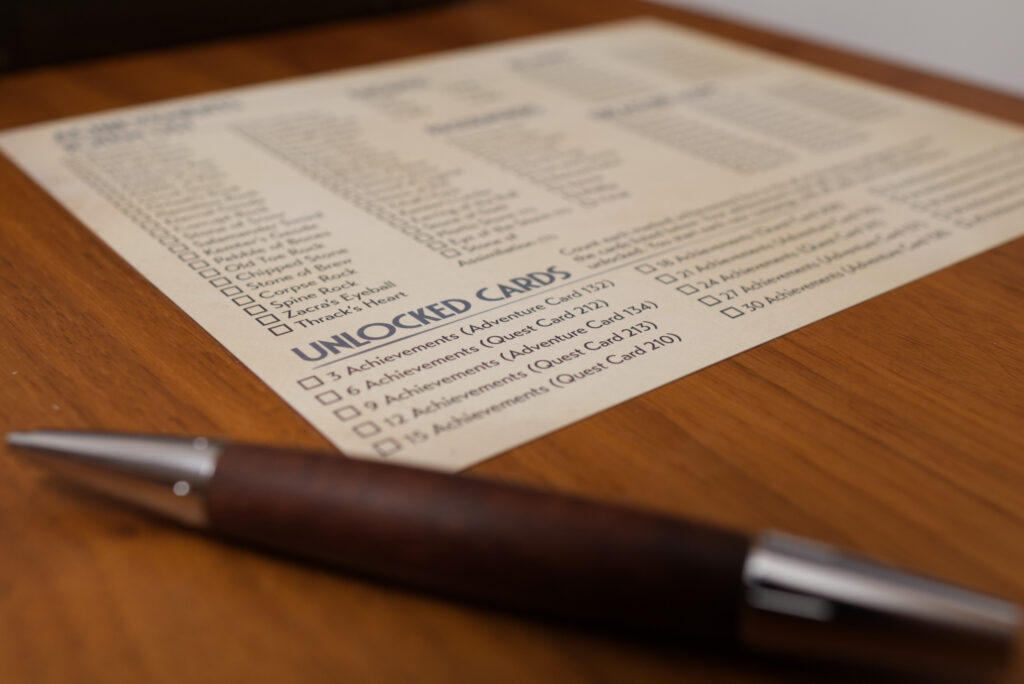

This combination of atlas map, encounter book, and quest cards had already worked very well in Sleeping Gods and so remains fundamentally unchanged. However, its application seems to be improved and extended. For one, more locations seem to have larger branching and/or reactions to keywords. In the original Sleeping Gods, there were a number of locations on the map that acted more as fillers to make the world come alive and had either short or very linear story arcs. Another improvement is that Sleeping Gods often operated with “end” quest cards, keywords players gained just to prevent them from executing certain encounters again. In Distant Skies, a lot of those cases are simply handled by instructing players to cross off the location on the quest log sheet’s map, which results in less active quest cards and again contributing to reduced clutter.

Distant Skies adds three completely new mechanisms though, chief among which is the separate plane track and miniature. While players typically travel the world by foot, there are locations throughout the map marked as potential landing spaces and a small side board tracks the current location of the plane. This acts as a fast-travel system, allowing players to move larger distances more quickly. The farther the plane flies, the more likely it will get damaged and players will have to spend actions to repair it again.

The plane also allows players to travel to so called “Distant Locations”, additional places in the world players unlock during the course of quests. A distant location is represented by a quest card with an image and an exploration number on it instead of the usual text description plus keyword. While they mechanically function exactly the same as flying with the plane on the atlas and exploring a location there, using distant locations allows the story to span a larger area than would be possible with the atlas. It’s a nice twist to be able to focus on a closer, more dense area for the main part of the narrative but still be able to let the world be bigger than just a couple of villages, even if it happens in the form of isolated spots. Unfortunately they feel more like detached side things than part of a single larger world.

In a similar vein, Distant Skies adds “Wandering Encounters”, mini maps included in the encounter book itself instead of on the atlas. While the distant locations zoom out, the wandering encounters zoom in on what is happening on the map. For example, where cities were purely represented by interlinked sections of text in Sleeping Gods, in Distant Skies there are situations where they are brought to live by an illustration. Mechanically, exploring a location on the atlas will lead the players to reveal an illustration in the encounter book which has multiple hot-spots on it that lead to quest cards or other effects. Players have to decide which character goes where and does what, as thematically this happens in parallel. The rules also instruct players to not read each of their gained quest cards out loud but instead re-tell in their own words what they have learned. This reminded me of how my groups play Pandemic, not allowing players to share exactly what cards they have to avoid alpha-gamer problems.

In essence, the world of Distant Skies is not “less” or “more” than that of the original Sleeping Gods, but different in perspective. It feels smaller in scope than Sleeping Gods but more dense and alive, resulting ultimately in a very similar amount of content and replayability while featuring reduced travel time.

Narrative & Characters

Similar to Sleeping Gods, Distant Skies also sets off players with an introduction that is separate from the rulebook. This guides players through a first skill check and combat without negative consequences, making them familiar with the base mechanisms before they have to dive into the full ruleset. It almost feels like a five minute “watch it play” which makes learning the game’s rules easier. New is that this introduction comes in the form of an illustrated comic. It gives the backstory of why the characters are stranded in the world of Sleeping Gods and sets up their motivations.

This actually results in one of the biggest changes from Sleeping Gods to Distant Skies. In Sleeping Gods, players followed the adventures of the crew of the ship “Manticore”, with one shared character called Captain Odessa and 8 additional crew members represented by character boards. Importantly, the writing was done in the third person such that players were not really inhabiting any of the protagonists but more felt like an unnamed member of the crew that was along for the ride. While not offering strong identification for the players with any single character, this worked surprisingly well. There was criticism that the individual characters didn’t really have much character development to them, but that was mostly a consequence of the non-linear narrative of Sleeping Gods. As flavours in the story and way to create a feeling of community, they worked really well.

Distant Skies drops this perspective and instead has all players together act as a single character, Claire Smith, who owns the plane that unexpectedly brings her and the passengers to this strange world. Make no mistake, there is no crew here. These are just people that happen to be together when disaster strikes. All narrative is written from Claire Smith’s perspective and in second-person view (i.e. “you see that …”), which is somewhat of an unusual choice for a potentially multiplayer experience. However, it opens up the possibility for the other characters to have more of their own unknown agenda and their own story/quest arcs throughout the campaign. Interestingly, as Brenna Asplund (one of the writers) pointed out to me, the writing in the original Sleeping Gods was also using the “you”-form but it always struck me more as a group you than a single person you. So much so, that I had filed it away as third person writing in my memory.

While there is now definite development, players should be cautious to not expect too much. The narrative is still very much about what happens in the world, as explored by Claire Smith, and less about any arc of any of the characters. But I’ve seen quests that are rather character-specific and elements being inserted into the even deck as a short-term timer.

Writing-wise, I would say it’s good but of course not on a best-seller book level. In short, the once slumbering gods are awake now but weakened and a group of people is again trying to find their way home. Totems are no longer hidden treasures that have to be uncovered but dormant stones that can be found relatively easy. The challenge lies more in finding the ingredients needed to rejuvenate them which feels slightly odd. Mechanically, it’s cool because one can – based on its name – venture a guess what a particular totem might do and then work towards activating that one first. But it just doesn’t feel as satisfying having to do random things until one suddenly gets that crystal one needs.

I haven’t encountered any glaring mistakes or obvious plot holes (unlike Stars of Akarios, which had some serious writing problems or the rather inconsequential story of Lands of Galzyr), not even typos, which is remarkable for the amount of content included. One thing of note is that there is less of the humour of Sleeping Gods in Distant Skies and things appear more serious. It’s still in the realm of fantastical and not thriller nor drama, but the tone definitely has shifted.

Setup

With that out of the way, let’s return to the more regular format and look at setup. Things have been streamlined compared to Sleeping Gods. As described before, there are 5 characters instead of 9, which already helps. The command tokens, a pseudo-currency of the original, have been completely removed and instead players discard ability cards to pay for equipping an ability (more on that later). The “boat board” of the original has been replaced by a simpler time track board (also more on that later).

The event deck has changed as well: in Sleeping Gods, the game utilised the event deck as the global timer of the game. Three times during a campaign, an event deck would be constructed out of different levels of difficulty (first easy, then mid, then hard cards) and after the third deck runs out, the game ended. In Distant Skies, this is no longer so, again cutting down on setup time. Events of the various difficulties are shuffled randomly and only the number of level 1 cards is changed during setup to adjust difficulty. If the event deck ever runs out, it is simply reshuffled. Of course this can lead to players being hit by a number of level 3 events during their fist turns where in Sleeping Gods the first few events of each deck would always be easier than the later ones.

Not having the three-deck-timer also removes one necessary but awkward element of the predecessor: the wipe of ability cards during mid game to reset power-levels. In Distant Skies, this no longer occurs. Instead an unusually high maximum of 8 ability cards can be equipped to each character but with increasing costs the more abilities a character already has. There are also elements that – as a result of a quest – might get inserted into the event deck, using it as a temporary timer to propel the story forward. As in Sleeping Gods, there are multiple possible endings but the most straight forward one is organically introduced through the story and can be triggered when the players feel ready for it.

So while there are a number of components, setup overall is rather quick for Distant Skies and mostly consists of shuffling some cards and pouring tokens into bowls.

The Turn

In the original Sleeping Gods, a turn starts by choosing one of multiple boat actions to gain ability cards, command tokens and other effects. Then an event (usually bad) is drawn and finally the active player can perform two actions such as exploring a location or traveling with the boat. In Distant Skies, there is instead an action point system representing time. The boat action has been completely dropped and instead the active player simply draws two new ability cards before performing the event (again, usually bad) of the round and then using 5 time (=action points).

There are five possible actions: travel by foot, travel by plane, explore a location, repair the plane, or making camp. The latter replaces the event deck as global timing component. On each campaign sheet, players have twelve (17 for a longer campaign) camps they can cross off at arbitrary times to refresh the stamina of their characters, remove a status effect such as being poisoned, and also refresh a little bit of health. That last part is interesting.

In original Sleeping Gods, players would go exploring and at some point run out of health or be too exhausted to continue. They could use recipe cards to convert resources (e.g. meat, vegetables) into health and remove exhaustion to extend on how long they could avoid the inevitable: having to travel to a port and heal/refresh themselves. If players ran into a particular bunch of bad luck or hadn’t acquired enough possible recipes, it could easily happen that an unfortunate group had to travel to ports rather frequently, slowing down the whole exploration and questing.

In Distant Skies, there is still the familiar cooking-of-resources mechanic but there are two factors that mitigate the port-problem: one) camps can be used at any time and at any location to refresh the crew and two) the “signalling” in the writing has much improved. If players act sensibly and don’t immediately start rushing into every dark alley they find, they can avoid a lot of conflicts completely and thus not run out of health. The impact of this is quite astonishing: in my first campaign, I had a total of three fights. Three! One was a big … I can’t tell you that. One a boss battle for a particularly powerful item, and the third a random encounter I could have easily avoided because I was on my way to somewhere else and thought “why not explore that … while I’m on the way?”. I had no reason to explore there other than being curious, and so it served me right to get into a bit of trouble for it.

Combined with the slimmed down turn structure and the fast travel system, this effectively means players are spending way more time exploring than traveling and – if they chose to do so – less time in combat. If they want though, they can easily follow down paths that immediately put them into dice chucking mode! In that case though, they will lose more health and have to put more actions into patching up their health again.

Combat

As is the theme of these first impressions, the combat again feels familiar but different. Both versions use a grid based system where players use over-sized, numbered cards to represent enemies. During a quest, the encounter book will say something like “Combat level 9, enemy 11, 12, 14” and then players search the ordered enemy deck for those cards and place them next to each other. The grid of each card represents sections of that enemy like its head or an arm, some contain hit points that need to be covered to win the fight while others represent special abilities that enemies will trigger at the end of each combat round (e.g. frightening a character so they no longer can fight).

The main difference is that Distant Skies now features a more dynamic combat-card-plus-die-roll system. In Sleeping Gods, players equipped weapons they acquired to characters and then they had to draw a card from the ability deck to generate a random number. If the precision of the weapon plus the random number was bigger than the enemy’s defence, they hit. In Distant Skies however, weapons are not permanently equipped to characters. Combat starts by selecting a subset of all combat cards the players have acquired, forming the combat deck. Then every player gets one card at random plus one for every character they pilot. When they want to attack, they play such a card on a character and that auto-hits, the question is just how much damage it does. Weapons usually have a fixed offset, 0-2 die rolls and sometimes added power due to a certain ability of the character (e.g. one power for each savvy symbol). There are also combat cards that can be used to distract the enemy and reduce the power with which they will retaliate. While it is thematically a bit weird to suddenly have a gun show up in a character’s hand, the dice role spices things up and it’s super quick to administer, making for a faster combat.

Enemies now also have power tokens and respective fields in their grid. If the players don’t cover those spots and/or actively manage to reduce the existing tokens, enemies will actually grow stronger and stronger from combat round to combat round. As with the original Sleeping Gods, combat feels to be designed for one to two full rounds of combat. Anything longer than that and the characters will usually run into problems as the remaining enemies grow stronger. Sleeping Gods was designed for a similar length, but it was much more tricky and more subject to good planning as well as some luck to actually pull it off successfully.

The synergy system of Sleeping Gods has been update as well. Again, there are certain grid spaces on the enemies that allow a player to place a synergy token on a character. Some weapons feature that symbol and thus synergy can be used to boost up the second character’s attack or defence depending on the weapon. It’s again a streamlining of the original mechanism (where synergy gave character specific bonuses such as +1 accuracy to other characters), turning the puzzly combo battles of Sleeping Gods into something more action-driven. It feels like the dice-chucking of Now or Never was a bit of an inspiration here, but it works quite differently.

And similar to what the wandering encounter do for exploration, there is a new side-mechanism: boss battles. These are full-page spreads in the encounter book, representing one or more enemies with usually the equivalent of three enemy cards but more powerful and with more hit targets. So depending on which quests you do and which paths you chose, you might suddenly stand in front of a giant … I won’t spoil that one either.

Another update to the core system is that most combats can now be fled from! It might sound strange to new players, but that actually wasn’t an option in Sleeping Gods. Ryan and I talked about this during our episode of Origin Stories. In practice, there are now two types of fights. Those one can abort (but in most cases cannot be re-attempted later on) and those one cannot flee from (important story bits). Again, it’s a quality of life thing that should make things more enjoyable for new players. But as I wrote before: if players pay attention and aren’t reckless, they can often avoid conflicts before they even start.

Skills Checks

Most quests will lead to some form of skill quest. As with the original Sleeping Gods, a majority of choices are “fail forward” meaning that if for example the party decides to climb a cliff, they will manage to do so either way but a failed skill check will cause them some serious damage. There are also those quests where a failed check will put players on a different path or end the encounter. But even the unluckiest group of characters ever will be able to achieve something, just not as much or as exciting things.

Each character has a set of skill symbols on them, from strength and crafting to savvy. When the players encounter a skill check, an arbitrary number (even none at all) of characters can join to add their symbols to the check. E.g. if there is a crafting 9 check and two characters contribute a total of four such symbols, the card they draw from the ability deck has to show at least a 5 to succeed. There are a number of ways to bolster the players’ chances:

Players can throw in ability cards with a matching symbol for a one-time effect, equip them permanently to characters (by discarding additional cards), or use one of the adventure cards they gathered during the campaign. This works similar to the combat cards in that all adventure cards are evenly divided between players and discarded when used. When the group camps, all adventure cards are shuffled again and divided between the players.

Again, this forces more communication but also removes table clutter. In original sleeping gods, both equipped weapons as well as a good 2-3 dozens of adventure cards would often claim a lot of table space. Now they are kept in the players’ hands. This mechanism also makes it easier for players to jump on/off campaigns because adding a player is as simple as assigning a character to pilot, re-distributing the adventure cards and that’s pretty much it.

Another simplification is that command tokens are no longer needed if an inactive player wants to contribute to skill checks. They simply spend one of the character’s stamina tokens and they are in. This improves the main flow and allowed removing the boat action from the top of the turn as well as the abilities for players to more easily recover being able to participate. As a reminder: in Sleeping Gods command tokens were both needed for participating in a check as well as equipping ability cards which caused players to run low on them all the time.

The main change however is that players can first draw the random ability card result and afterwards decide if they want to pitch in additional cards. In the original Sleeping Gods, this had to happen before the card draw, making it a much more risky endeavor.

Production and Crowdfunding Content

Besides the plane miniature, there are now some plastic miniatures for the characters. In most cases though, the players will just move Clair Smith on the map with the other characters only used for wandering encounters. I actually packed all of them away after a while and opted for the nicely illustrated cardboard standees. The plane mini is beautiful though and pre-painted. It’s a bit of a shame it is so rarely used compared to the Manticore in the original Sleeping Gods.

I also didn’t play with the Thunderstorm Island expansion which adds some extra content, so I cannot really comment on that. But there feels to be more than enough content in the base game for many campaigns even without it.

The metal stamina tokens are actually quite nice. Ryan Laukat has a great track record when it comes to designing metal pieces (e.g. see coins from Sleeping Gods, Now or Never, Empires of the Void II, Roam) and doesn’t disappoint here either. Since they are used quite frequently, it’s nice to have them.

Overall I would say if you have a chance to get a retail copy (whenever it comes out), you’re good to go and won’t necessarily miss the extra stuff.

Multiple Campaigns & Replay Value

With the major mechanisms out of the way, let’s briefly talk about replay value. As said before, the world of Distant Skies feels somewhat smaller in scope but denser and more alive. Even on the first map, there are multiple situations where players can chose the path of caution or stumble into serious trouble, and choosing one will block off the other for that campaign. This enables more experienced players to either dare the more risky path or use learned wisdom and simply come to that encounter later in their campaign when they are better equipped.

The original Sleeping Gods featured an unlock system where based on how well players did and how many campaigns they had played overall, new cards were unlocked for the start of the next campaign. This always felt to me like a missed opportunity because those never changed the world in a fundamental way. Without spoiling anything for Distant Skies and not having started a second campaign myself, the unlocked cards seem to enable some new avenues and possibilities for which things to tackle at the start of a campaign. Less in a major way but more smaller shifts that give incentives to try things differently or head in a different direction. The major thing that impacts a campaign will probably still be the approach the players take: cautious vs adventures, greedy vs righteous, etc. But that is speculation. Further campaigns will show what’s what.

There are also whole side-mechanisms I haven’t mentioned because they are introduced organically as part of the story, from supporting factions, solving riddles, to finding certain locations. With the exception of the first, think rather optional mini games that add “more”.

Conclusion

As you will have noticed, the overall theme here is: similar, but different. In fact, players that have played the original Sleeping Gods will have an easy time getting into this one. Yes, there are many new mechanisms, but they all feel like either small rules adjustments or usages of the existing system in a new way. Take for example the Wandering Encounters: anyone that knows how skill checks and exploration works can be taught this in a minute. Similarly, boss battles are just an extension of the normal card combat, Distant Locations just another point to explore, and so on.

Distant Skies is a noticeably smoother experience, both to learn as well as to play. The rules are structured better, some elements like command tokens have been simplified into other mechanisms (i.e. discarding cards and stamina tokens), and the overall round structure spends less time on overheard and more on traveling and exploring. There are many quality of life improvements like players no longer having to travel to ports to get back to health or that resource tokens can be used for some small effects without any need to play an adventure card such as a recipe.

The improved “signalling” in the writing also makes for a better experience. With some common sense and attention, players can steer their campaign towards the type of experience they want. Want to be super efficient and complete the main quest line as quick as possible? Go for it. Want lots of fights? It’s got you covered. Want to run around and collect as many cool things as you can? You can do that too. In my campaign, I tried to play the characters as rather sensible and focused, which led me to avoid any combat at all for the first 3 hours of my campaign. Overall I played under 8 hours and had used only half of the available camps before I was able to successfully trigger an ending (there are of course again multiple possible ones). I think experience with Sleeping Gods helped and a bit of luck in the abilities I drew might also have had a part in this. My guess is that a more normal campaign would rather take around 10-11 hours. Side note: it does feel like a campaign of Distant Skies would be easier to pause and resume than Sleeping Gods.

I think there are still some improvements that could be made, such as printing the location where a quest card was gained onto the card itself for easier reference or having the events be different based on which map the players are on so they match the climate. But those are only minor quibbles. It’s a rounded, well running system. Many new players will prefer the easier entry into the world of Sleeping Gods as provided by Distant Skies, but there are some essential differences that make Distant Skies a substantially different experience than Sleeping Gods.

For one, there is the main metaphor: Sleeping Gods with its boat as the personification on the map and this crew of which the players could be part of as unnamed participants created a great immersion into the world. I unfortunately never really felt that attached to Claire Smith and using the second person perspective as a writing-style pulled me out of the experience multiple times. In fact, I just had to look up her name in the rules because I had already forgotten it. Walking on the map with this grey mini of a single figure that suddenly springs into multiple characters when running into a wandering encounter didn’t help as well. It’s a shame that the plane mini looks so glorious but is now banned to the side line. It didn’t take long before I put the minis back into the box and used the nicely illustrated cardboard standees (without propping them up) instead. The idea of using this different perspective and thus giving the other characters space to develop was a good one in principle, but in reality for me didn’t have a payoff that would be big enough to give up on this communal feeling of a “we are all stuck together on this boat stranded in a foreign land”.

My favourite aspect of the original Sleeping Gods was this feeling of freedom to explore. In many ways, it was a game about world building rather than telling any single story. Sometimes I would start a campaign by just saying “let’s head east and see what’s there” or we’d be traveling somewhere and on the way would stop, thinking “what is that small blob of colour there?”. Since the area in which Distant Skies plays out is smaller in scope, this isn’t possible as much anymore. Instead, players act more with a purpose, following up leads they gained during quests. I would have thought I’d like this better, but seeing the comparison now, I miss that part of the experience.

While I did many things that were mechanically interesting, I didn’t have this sense of world exploration that brought me so much joy in the first one. I also miss the old combat system, although it was more punishing and more puzzly. But it felt so much more evocative, raising images of one character slashing off an arm and causing splash damage in a close by enemy. Even the fact that I sometimes would stumble down the wrong alley and suddenly the game would chomp my head off is something I now appreciate more.

My second favourite aspect of Sleeping Gods was the humour, those strange encounters where we would laugh out loud and speak about it in the days or weeks afterwards. Those are some of my most memorable moments of Sleeping Gods. It is the same quality that endeared me to Ryan Laukat’s earlier title Near and Far. In Distant Skies, I didn’t have those to that degree. For one, the tone is more sincere. I feel Distant Skies is a first step towards the tougher/scarier game Ryan had originally planned Sleeping Gods to be.

All of this puts me in a weird position: Distant Skies is in pretty much all mechanical aspects (the vote is still out on the combat) a huge improvement and an excellent iteration of the system we were first introduced to in Sleeping Gods. It requires less table space, is more forgiving, provides a wider range of scale, some form of permanence and development (by giving characters quest lines and using in-deck timers), etc. I’m almost certain going back to Sleeping Gods will come as a mild shock after getting used to the smooth game flow of its sequel. But if I’d be honest which one I would pick for my next campaign, it would likely be the original Sleeping Gods. There is still so much content in there I haven’t explored, so much joy for me to see old acquaintances, dungeons I haven’t been in to or quests I still haven’t found the next waypoint for. Gosh, I haven’t even had the chance to use the diving suit yet. It also left more room for the imagination, whether it was just reading about city life instead of seeing a Wandering Encounter, reading the introduction instead of having it illustrated, or the more detailed map.

I like to work with images in these write-ups and the best one I could come up with so far is the following: Sleeping Gods feels like the video game Zelda, that pure joy of seeing what is around the next hill. It’s over saturated, quirky, but endearing as heck. Distant Skies reminds me more of the Uncharted series, minus the mindless gun battles. It’s still fun but more serious, tries to tell a more consistent narrative, guides players into the right direction instead of having them get lost, and at times even helps them sidestep hurdles, all in an attempt to create a smoother playing experience.

As a result, both games feel more complementary than additive to me. I can see Distant Skies click for players that were – for whatever reason – struggling to enjoy Sleeping Gods. The teach is easier, one can flee most combat, the signalling is better, less jokey, less random, etc. I would even go as far as to say that for everyone except heavy gamers, Distant Skies is probably the better choice as a first entry in the series. What I personally had hoped for was something additive, something that would take the world of Sleeping Gods I love and add its next chapter to it. That design decision, if it was a conscious one, might be a sensible one: me, I still have tons to explore in Sleeping Gods, I’m good. Distant Skies can (and already has, based on the reaction in the BGG forums) open up this world to brand new players. Story-wise, there is no reason to not just start with the more streamlined Distant Skies and only later come to the original Sleeping Gods.

One thing I’ve learned though playing Sleeping Gods is that with this type of game, even a full campaign can only qualify as a very early first impression. During my eighth campaign of Sleeping Gods, I suddenly discovered an alternate ending that allowed me to bring my crew home safely and keep the world in its best possible state while ending the game early during the second of three event deck! That was previously unimaginable. I had skipped a whole third of the game and came out far ahead. I had to win a very, very tough fight for it, but in the end it all worked out. If things like these are possible in the world and system of Sleeping Gods, who knows what depths Distant Skies will hold …?

I’ve been playing my first campaign of distant skies for a few weeks now with a friend and it’s amazing!

But I have to ask about the rule you are talking about in sleeping gods where you have to choose which adventure cards to use BEFORE you draw fate. I even looked it up in the rulebook, you use adventurecards AFTER drawing fate, same as in distant skies. Or have we been playing it wrong?

Thanks for the reminder! Another reader also pointed that out and I forgot to update the text. Apparently I had played it wrong and/or misremembered the timing in the original Sleeping Gods. So you’re playing it correctly. Will fix the text now.

My daughter and I just finished our first campaign. We did a long campaign that lasted about 14 hours total and had an absolute blast. We loved the original, but, to my mind, Distant Skies is even better. We really liked the improvements to the system. Adventure and ability cards were much easier to manage, especially because we weren’t limited by command. That meant we could make full use of our adventure cards. Camping is a much more fun way of both regaining stamina and healing, and progressing towards the end of the game. The combat system is also a blast — especially in the beginning when the weapons are underpowered. By the end, though, our party was pretty much a tank that could roll over anything, including bosses.

There are a lot fewer endings, which I didn’t have an issue with. The joy of the game, for us, is exploration and quests, and Distant Skies had so much more of that. We played for 14 hours, and I think we may have seen 25% of the game? We did thoroughly explore Thunderstorm Isle, which was a really fun, self-contained quest, but there are plenty of regions we didn’t explore.

Another nice addition is that, if we do a second campaign, we get some REMOVED_SPOILER right at the beginning, which means we could strike out for more distant, difficult locations without having to slog through encounters we’d already done, just to power up enough to survive the unexplored territory.

Definitely a top 5 all time game for me!

Thanks for commenting, loved to read that! Didn’t you have the feeling that that sense of exploration and wonder was lost a bit? I think that’s the biggest difference for me. With the original I was always curious and thinking “oh, I should go there and see what’s that” where in Distant Skies the art on the map had much less relevance for me. It felt like a bit like “play by numbers”.

No, not really. I loved all the distant locations, the wandering encounters, the boss fights. think there were more tiny details on the map in Sleeping Gods, but it didn’t really affect my enjoyment.