You are a game designer and looking for a challenge? Well there is the holy grail of creating a true civilisation game that can be played in under two hours (and no, Mosaic isn’t it). There is the endless adventure game (Lands of Galzyr technically did it, but what is an adventure if there is no progress?). Both are eluding but feel possible and within arms reach. But imagine being tasked with the following: create a solo-only game that’s both challenging and approachable, basically only consists of cards so production costs are not crazy, and is of all things a word game! Who in the world would be crazy enough to design or even publish that one? To which Tim Fowers and Skye Larsen say: “hold our beers” …

Okay, truth be told, the origin story of Paperback Adventures is likely more a case of “I love Slay the Spire, can we combine that with a word game?”. But it would still be the odd one out at any game designers’ meet-up. While there exists of course a strong Scrabble community, taking random letters to form words is a rather small niche in the board gaming hobby. I never liked Scrabble and thus was surprised when the original Paperback came around and I quite enjoyed it. I added its follow-up Hardback to my collection shortly after binging the iOS app for a couple of weeks, but both rarely see the table in my groups. While fun, they are not exactly the type of game you organise an evening of board gaming for. Having something like them in solo-form actually got me really interested because that opens up the possibility for repeated plays by a lot. But would I need 100€ (incl. shipping and VAT) of it to justify joining the Kickstarter?

I decided no and months passed by in perfect bliss. But for some reason, whenever Efka of No Pun Included talks really enthusiastically about a game, my bank balance has the tendency to go down a couple minutes later …

Setup

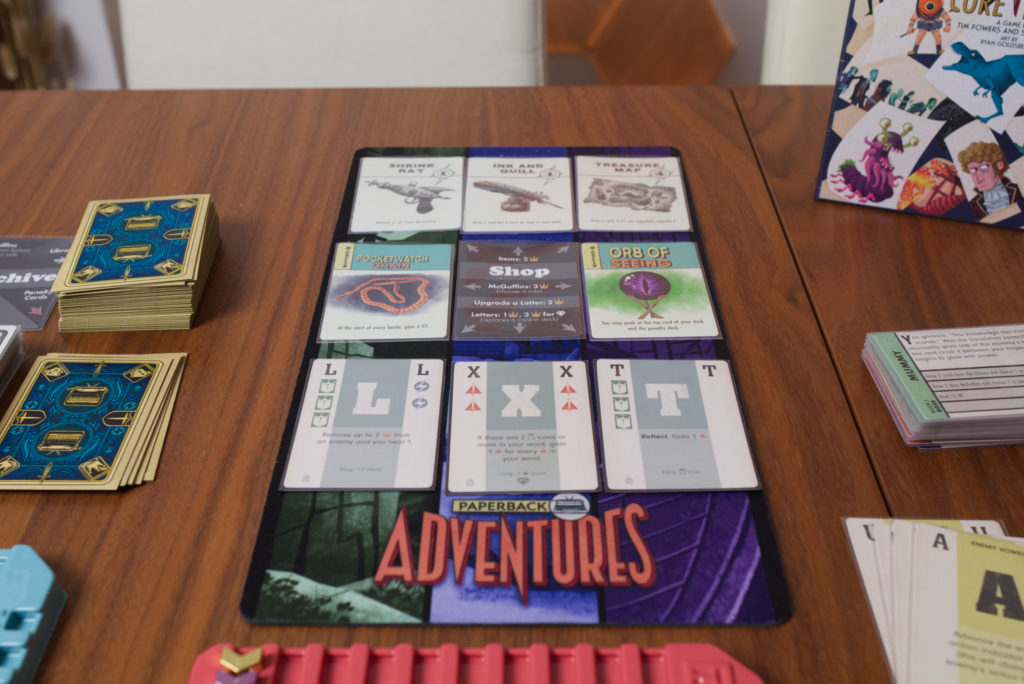

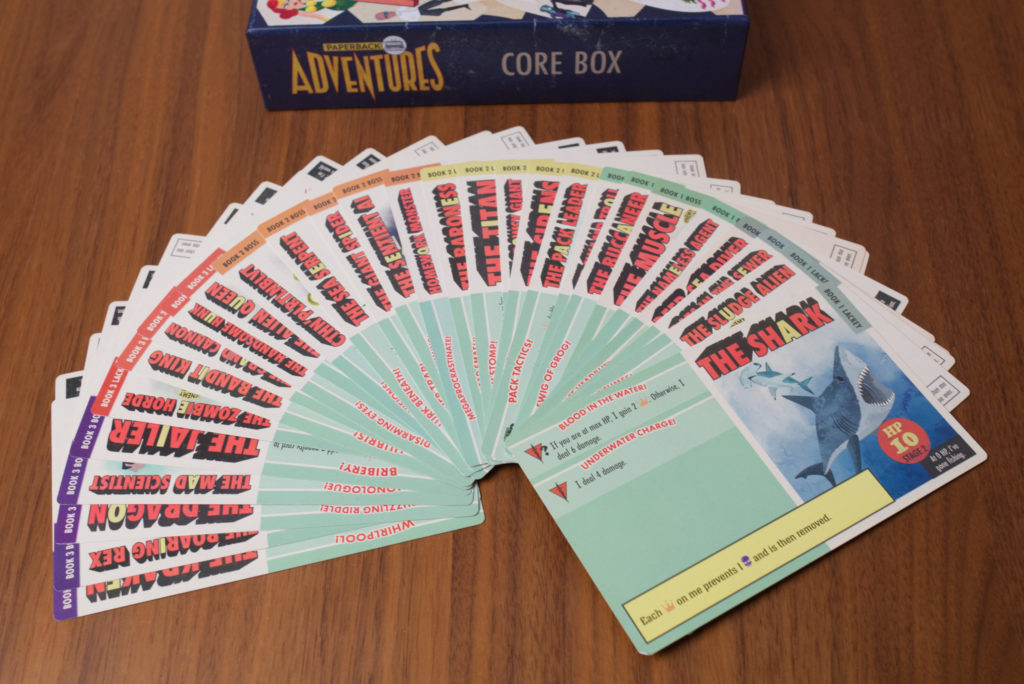

Paperback Adventures comes in four boxes of which you need at least two. There is the core box that contains a plastic tray that can hold an over-sized enemy card in the middle and various metal markers on the track around it to show its properties such as health. There are also various types of cards as well as sleeves. That’s not an indication on where the authors lie on the great sleeves-vs-non-sleeves debate but rather a necessary element of the game. All of the letter cards have a normal and an upgraded side to them, so they are put into sleeves with an opaque back. There are also various items and MacGuffins that can be gained between battles to provide the player with a fighting chance to deal with the increasingly more powerful enemies throughout the 6 battles of a full play-through. The core box comes with a small selection of such enemies, split into three levels and the two categories of lackeys and bosses for each level. The game starts with a level 1 lackey and ends once a level 3 boss is defeated – or – with the player’s character running out of health.

The three character boxes are all structurally the same: they contain a complete separate set of letter cards (the core box only contains general cards like items, penalties, etc) with abilities unique to that character. Damsel is all about short, effective words and offensiveness (kind of for the Wordle addicts out there), Ex Machina often needs to ramp up a bit before dealing huge blows, and Plothook is about drawing additional cards and building longer words (for the Scrabble fans out there). Think of each character box as a slightly different game and the core box being the necessary components to play it.

Each character comes with another of the aforementioned trays, this time to hold the card and markers used to represent the human player’s character, as well as two character specific usages of boons and hexes (=thinks that can be collected by playing certain cards). There are also additional items, enemies, etc. While the letter cards are distinct sets that cannot be combined, enemies and items can be mixed and therefore having more character boxes increases the variety of “stuff” you’ll encounter.

So to set up the game, one selects a character and puts the content from that box as well as the core box into their piles, picks a random level 1 lackey, takes that character’s starting item and abilities, and separates the specially marked 10 starting letter cards into the initial draw deck. The human character always starts the game with 20 health, the enemies health marker is set to whatever value is printed on the enemy card.

The Turn

A turn starts with an initial hand of just 4 letters and two special cards: a wild card that acts as a joker and a vowel card matching the highlighted character in the enemy’s name. The player forms a valid word, potentially uses items and abilities they own, and then calculates how many attack, defence and power symbols they generate. This is decided by the direction the cards are overlapping (called splaying). If the left-most card is on top, only symbols on the right side of cards count (even ignoring those visible on the left of the top card). This usually means an attack as the attack symbols are predominantly found on the right side of cards. If instead the right-most card is on top, only the symbols on the left side of each card count, which are pre-dominantly defence symbols. Power symbols can be found on either side.

In addition, the unique ability text found on the topmost card is triggered and that card is taken out of game for this battle (called fatiguing). This has multiple interesting consequences at once: in general, the player will want to build a word that is as long as possible with the available letters in order to gain as many symbols as possible. But the abilities printed on the cards are so powerful that it often can be more lucrative to construct a slightly shorter word but have a particular card as first or last letter depending on the direction one overlaps the cards. Other times, the player will want to specially not have a certain card as top card because that means it will go out of play (for that battle) and never contribute its symbols again. It’s difficult to describe, but it can actually make your head hurt as finding the best move is not simply building the longest possible word.

The player then counts the number of attack symbols and reduces the enemy’s health by that number. Then the enemy will usually strike back. I say usually because each enemy has different phases it cycles through. For example, the shark level 1 enemy will not deal any damage on the first turn but then strike on the second and third. Some enemies are rather straight forward, others have a particular rhythm to them. The diversity here is quite remarkable and deciphering how to avoid the phases where an enemy deals a heavy blow is among the most interesting aspects of the game.

There are two ways to avoid a particular phase. If the enemy vowel card is the top-most card, the enemy will skip a phase (but the card is fatigued, leaving you with one less vowel). The other way is to “stun” the enemy by lowering its health to zero. In that case, it won’t strike back that turn and instead flip to its reverse side where it has different characteristics and/or attack patterns … and its health is unfortunately refreshed. Thematically, this is done very well. There are some enemies where it’s best to stun them as quickly as possible while with others the front side is chance to buff up for what is to come on the reverse (e.g. a slumbering dragon).

Overarching all of this, there is a huge problem: time is ticking. Since the top card of every turn is fatigued, the player’s deck is running out of cards, and running out fast! Remember that the initial starting deck consists of only 10 cards. Even though finishing enemies will add a few additional cards, the deck will overall stay rather tiny. Deck manipulation is usually restricted to replacing or upgrading cards, not adding.

Between Battles

Each enemy comes with a specific card listing two options for rewards. Both sides are a mix of gaining health, getting items, upgrading letter cards, getting MacGuffins (powerful permanent abilities), etc. Typically, one side restores more health while the other provides better functionality (e.g. grant 2 items instead of 1). Note that the player’s health is not automatically restored after a battle. Instead, the player must use the battle rewards and a few letter card abilities to restore lost health on the way. The typical way to lose the game is by going into a level 3 battle already low on health and then not being able to sustain the huge damage dealt by the later enemies.

There is also a shop from which letters, items, and MacGuffins can be bought during battles. However, for this the player needs to gather boons during battle, which can for the most part only be done by triggering the special ability of certain letter cards (and thus using less of those abilities that make the player’s attack/defence stronger). So besides attacking and defending, the player will also sometimes sneak in such a card and save up for shopping later on.

Once all of this is done, the player randomly choses an enemies of the next type or level (level 1 lackey is followed by level 1 boss is followed by level 2 lackey, etc), shuffles all fatigued cards back into their deck and starts again by drawing 4 cards.

End of Game

The player has won if they manage to defeat the level 3 boss before running out of health themself. As a reward, each character box contains a sealed envelope with a couple of additional cards that can be used for future games. Some change the base character properties, others are just additional MacGuffins or items.

Two-Player Mode

Yes, there is a two player mode. I played it once, it works, but it’s not that I’m planning to ever use it again. This is definitely a solo experience first and foremost. But if your significant other also enjoys word games, this might be an option.

Production, Character Boxes and Accessories

The minimal option to play Paperback Adventures is to buy the core box and one character box. My recommendation goes towards Damsel as I enjoyed the offensive, shorter words the most. However, with only one box, player’s will soon encounter the same enemies over and over again. Still, due to the game’s price point, I would recommend getting a single character box to start with and only adding more if this is really the game for you. While the characters do play differently, for me the real values is in getting the additional items, MacGuffins, and especially Enemies to shuffle into the core box. The idea of giving potential buyers the choice of what kind of word game they want (e.g. do you want Wordle or Scrabble) is interesting, but I think I would have preferred a complete base game consisting of core components plus Damsel (and even more enemies) and releasing additional characters as expansions.

The production itself is a bit unusual, starting with the rather cheap plastic feel of the trays. I think I would have actually preferred a board and wooden markers to the plastic with metal markers situation here. The card design itself is rather bland and the upgraded and non-upgraded card sides are only distinguished by small text at the bottom of the card. This can be a problem because if one doesn’t remember resetting (i.e. taking the card out of its sleeve, flipping it, and putting it back in) all cards at the end of a game, one can easily start a new game with some upgraded cards by accident. The number of sleeves also is exactly what is needed for the game with no sparse, though Fowers Games has responded in BGG threads that they would ship replacements in case sleeves should really break.

Speaking of which: while the opaque sleeves with the artwork on the back look very nice, the sides quickly start to separate a bit as a result of all the shuffling. In my copy, I can tell which cards in the deck belong to the 10 starting cards simply by feel. It’s not a problem game-wise, but it kind of feels odd to have nice, game-specific (=no way to buy replacements) sleeves and then noticing them wearing off so soon. The bigger issue of the initial print run were the metal markers that get slotted into the plastic trays. The idea here was that they should be so snuck that players could interrupt and save their game by just packing the trays back into the box. Unfortunately this led to them being so snuck that they often bounced out of their groove right after pressing them in. The publisher offers slightly smaller replacement markers which I got and they are a great relief. The game state cannot be saved that easily anymore, but at least I don’t have my game flow interrupted because I’m trying to push in the same marker for the fourth time and it still bounces out of its groove. But if the saving part doesn’t work, we might as well have gotten nicely illustrated cardboard boards instead of trays.

There is also an optional playmat and my recommendation here would be: forget about it. It comes in the shape of an elongated mouse pad and for some reason only has enough space to hold the shop, not the archive (where the additional items, penalty cards, etc are kept), let alone the player area. I don’t get the thinking behind the playmat. There are no marked spaces on it, not enough space to fit everything on it … perhaps I’m missing something, but it still leaves me puzzled why it exists.

I can wholeheartedly recommend another accessory though: getting a Scrabble-dictionary. It may sound weird but this has increased my enjoyment of the game by a lot! It’s not what you think though: I don’t cheat in games, it’s just that it keeps me from having to get my phone out and google the exact spelling of some obscure word I’m thinking of.

Conclusion

To be honest, even after about two dozens of plays, I’m not quite sure what to make of Paperback Adventures. On the one hand, I admire its cleverness. The enemies for example feel thematic and pleasantly varied. Before starting a battle, one has to form a rough strategy when to attack and when to defend, how soon to try to stun the enemy, when exactly to use the enemy vowel to skip an enemy’s response, or whether one wants to deal direct damage or use hexes (yet another aspect of the game I haven’t even discussed in the above description). The constant conflict between trying to produce long words but also splay (=overlay) the cards in the needed direction, having the right card on top to use its ability, etc is great. Having the top-card go out of play is also a well chosen mechanism and reminded me of Watergate where one is also struggling between a really good one-time effect and the potential repeated use when keeping the card in play.

On the other hand, the game packs a lot of mechanism into a single game, maybe too many. Besides the above core aspects, there are items (need power to activate), MacGuffins (permanent abilities), Boss MacGuffins (even better), upgrading of cards, enemy vowels, character abilities, unique card powers specific to each character, penalty cards, boons for the shop system, letter of your choice (which are not the same as the wild cards) … It’s quite easy to overlook something or be overwhelmed. Just as an example: I played Paperback Adventures today and only halfway through the game realised that the wild card generates one power every time it is not used. I’ve been playing this game so much and now only by chance found out I had played it wrong all the time. I had similar moments after my initial 5-6 plays where I read something on BGG and noticed a rule I hadn’t quite got right that changed a lot!

The other downside for me might be related to a) not being an aficionado of word games and b) a non-native English speaker. Every turn, one is tasked with finding a word that maximises efficiency. Since one is losing one card each turn, time is running out and there is the need to make the most out of each turn. Just having one more letter used in your word can make a huge difference. However, this means that even if I find a pretty good word, it’s now up to me to decide whether I want to spent the next 10-20 minutes searching for an even better word (because otherwise I might not have a chance to finish off the enemy in time) or wing it and just go with the word I have. As nice as Paperback Adventures’ flow of playing multiple quick hands and each battle only being a couple of turns is, this efficiency factor often caused the game to grind to a hold for me. It didn’t feel like a quick battle but a prolonged consecutive series of word puzzles. On some level, I enjoyed these moments, making myself a tea and trying to come up with something even better. But I noticed that if this happened, the game overstayed its welcome and I often didn’t finish the whole 6-enemy campaign.

So where does that leave me? I guess with no real conclusion and the strong reminder that these first impressions and reviews I write are intended for you to make up your own mind. I think it’s safe to say that Paperback Adventures is by far the cleverest, most fun word game I have ever played. However, if you are not specifically looking for a word game, the equation is quite different. Paperback Adventure is quite pricey and it can be AP inducing to a point where I’m seriously considering playing with a sand timer although I’m the only player! Yet again, its thematic integration is lovely. From the name and functions of the MacGuffins to how the enemies work, this game has an abundance of charm to it. Whether you need it in your collection is a tough call and one that you will need to make for yourself. Personally, I think the original Paperback is more what I’m looking for. It feels faster, more in flow. But if you like a good word puzzle and scratching your head while rummaging your brain for the perfect word that ends specifically with the letter “O”, this is for you.