It’s quite remarkable how fast the initial buzz about Horseless Carriage has subsided. Simply by the fact of being another game from publisher Splotter Spellen, known for their innovative and often quirky games, many had anticipated it with great excitement. The theme also sounded interesting: building and selling cars in an early era of automobiles where what constitutes a car wasn’t as clear as it is today. Breaks? Interesting concept. Windshields? Who’s gone pay for that?

But now, a couple of months in, there is little to be heard of this game and many popular YouTubers and podcasters have never followed up on what were clearly impressions after a first initial playthrough. So what’s the story here? How can a game this anticipated be off most radars so quickly?

Setup

Handling the box of Horseless Carriage reminds me a lot of The Colonist: packed to the brim with cardboard, this is a hefty beast! Luckily, setup doesn’t take long though as it is mostly about opening zip-lock bags, pouring dozens of different tiles into whatever bowls you own, and preparing stacks of cardboard tiles next to the board. Despite its normal-sized board, this game requires quite a large table to fit everything you need plus additional space for the 3 to 5 players onto it… which might be the first two aspects where Horseless Carriage loses some of its potential audience: sprawling table space and not having a 1-2p mode. Another is that a large part of what is in the box is either white, black or various shades of grey. While this produces contrast to the coloured player components and (even slightly shiny) wooden cars, the presentation is an unusual and somewhat bold choice in an age of over-produced Kickstarter games and Eagle Gryphon deluxe editions.

Besides unpacking, setup is rather simple: unfold the shared main board, seed some initial buyers (represented by the small wooden cars) in the market area, place two cardboard dimensions of demand tracks (e.g. “range”, “speed”) and place one on each axis of the market area with the other 3 remaining next to the game board for now. The only slightly annoying part is that for each technology tile, a certain number of pieces are taken out of game according to player count.

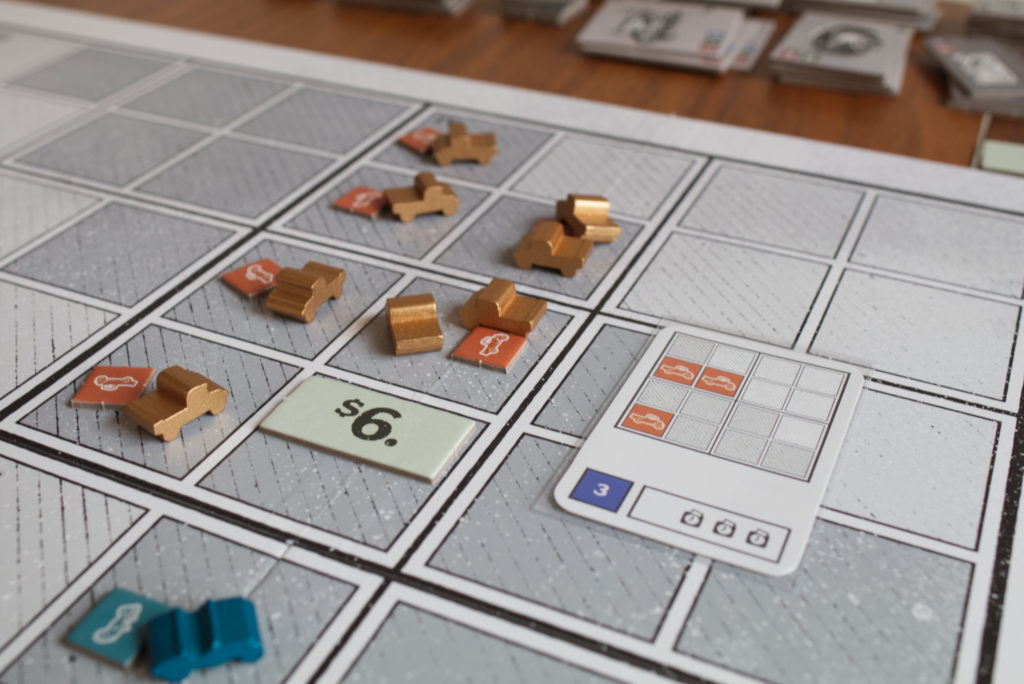

Taking a closer look at the market, it is broken down into a grid of squares (called niches), each one being a unique opportunity to sell to customers. The more towards the top-right corner a niche is, the more money that customer is willing to spent but also their requirements are higher. That’s where the two axes printed on the border come in. The dimension of demand next to an axis indicates what type of technological advancement the buyer is interested in and the scale on the mainboard indicates how much of that technology they require. Initially this ranges from zero to three things your car must have but can grow to two to five during the course of the game. If the car that you are producing has at least that much stuff in there, great. If not, you won’t be able to sell it here and have to chose a niche with lower requirements (and thus lower earnings).

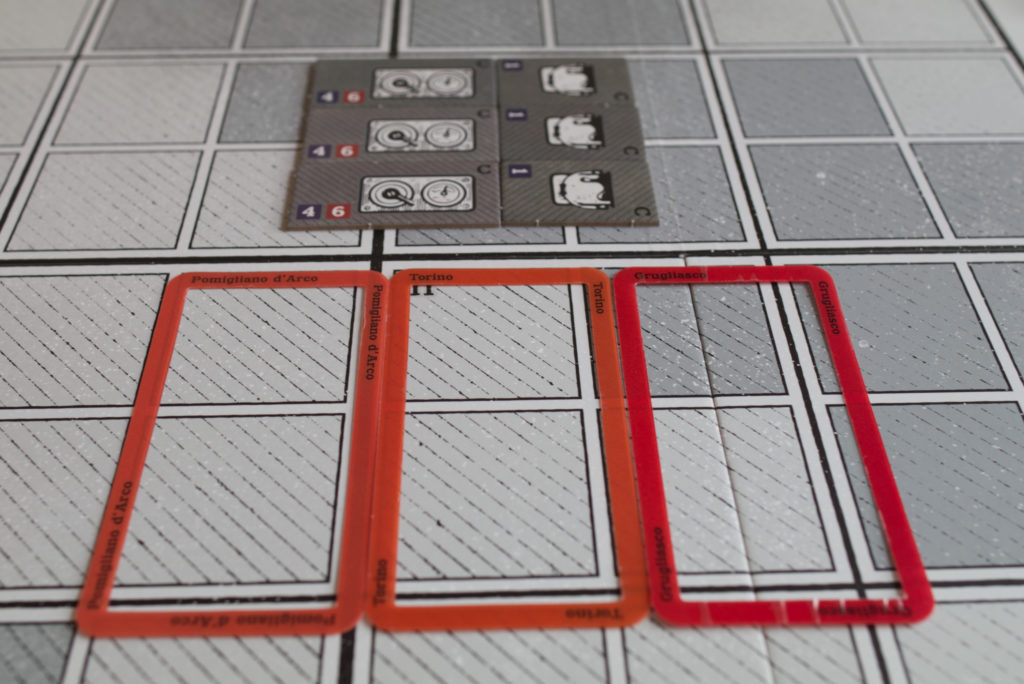

The other half of the main board is occupied by a couple of tracks for VP scoring (representing wealth you collect by selling cars), player order and so on. Place wooden markers on all those tracks as well as on the dimensions’ cardboard tracks to indicate what technologies you have currently access to. Each player also gets an empty factory floor plan they will use to construct their manufacturing lines as well as some thin plastic frames used to mark in which areas of the market they will be able to sell their products. The players then place one planning and one research department tile into their factor and setup is complete.

It must be stressed here how little randomness there is in Horseless Carriage and all of it happens during setup. What is the order of demand dimensions, what is the initial player turn order, and where are the initial buyers? That’s it. Whatever happens after that is the intentional or unintentional result of what a player did during their turn.

Research & Player Order

A round of Horseless Carriage proceeds in 8 phases which sounds more complicated that it is in actuality. First players can do research and advance markers on the various dimensions to get access to more technoloy. Note that I wrote markers, not their own markers. For each research department they have built in their factory, they can move one marker, either their own or an opponent’s, as long as they don’t move the same marker twice. We’ll see shortly why it can make sense to advance an opponent. In addition, they can also increase their own assembly capacity, the number of cars each of their production lines will produce later on.

Advancing technologies has two effects: one, you get access to more things you can add to your factory. Two, towards the end of the round, customer demand changes and one of the dimensions currently in play is replaced by the in-active dimension that has the most advancement on it. Or to put it in other words: invest in the two active dimensions to increase your chances of selling to high value customers now, invest in the three in-active dimensions to influence what the demand next round will be. This phase is typically over rather quickly, but its influence can be felt throughout the rest of the turn and into the next round.

Next up, players decide the new turn order. By building planning departments into their factory, they gather steps on the Gantt chart track. In the reverse order of that track, players can decide if they do nothing or spent all their accumulated Gantt charts to select one of the still available spots in player order. An earlier spot makes it easier to build their factory (more on that later) but a later spot can also be valuable because it allows that player to sell first. The agonising part here is that one loses all Gantt charts at once and players have to carefully weigh if right now is the time to spent it all and get the spot they need or if they should rather save it for a later round. All players that did nothing stay in their relative order and fill the spots that weren’t claimed this round.

Build Factory

The third and longest phase is the build phase. And it’s quite unusual: Players can pick up any number of planning departments, research departments, mainlines (the source of a car production), dealerships (allow selling those produced cars), advertisement (increase the sales radius of a dealership) as well as all technologies they have access to via their position on the dimensions. E.g. if you are on the third space on the “speed” dimension, you can build engines, horns, and gear boxes but only engines and horns if you are on the second spot. Everything mentioned previously is a rectangle piece of cardboard of various sizes. Engines are huge while a horn takes up almost no space at all.

There is no limit to how many of those titles a player picks up. There is no price to pay and as long as your co-players haven’t used up the available tiles, there is nothing keeping you from putting it into their factory … nothing except space and a couple building restricts. First of all, everything you want to put into your factory has to fit in, no overlaps and all. This is a tall order because space is at a premium and some pieces are huge. While you are technically allowed to build multiple production lines in the very first round, you literally run out of space in a heartbeat and won’t be able to fit it in. Second, everything you build must be adjacent to an existing tile or the shaded loading bay area. Third, if you build a mainline, you must place it next to a dealership (and vice versa). There are a few more additions, but that’s the gist of it.

The other limiting factor is that each piece of technology is associated with a background pattern / letter (A-D) and can only be connected to a certain side of your mainline or another tile of the same background / letter. This creates clusters of tiles of the same category which you might be able to connect to multiple mainlines, giving each one all the benefits of the whole cluster. And finally, the game comes with a bunch of small 1×1 arrows that you need to point to the technology to indicate towards what dimension it counts. For example, if you have access to the engine tile via the speed dimensions, you point a red arrow to it. If you later manage to unlock the engine tech via the range dimension as well, you can add a blue arrow as well and the engine will count in both dimensions for you.

It’s a bit tricky to explain but becomes quite natural after the initial 1-2 rounds. Basically you want to get tech tiles connected to your mainlines so they fulfil the demands customers have but waste as little factory space as you can doing so. One way to do it is to place your mainlines that they share 2 or even 3 clusters of tech among them. Another is to only build what you need to satisfy demand and hold on other tech until you really need it. To make things easier to read, coloured wooden cubes are placed on the dealerships to indicate what configuration of car that dealership can sell (based on the mainlines next to it).

A particular juicy part of it all is the effect the player order has on building: if you are first player, you not only have access to all the technology you have unlocked, but also that of every other player. If you are second, you have access to everything that at least two players have unlocked, and so on. This puts pressure on players to use this time-limited access and add those technologies to their factory. However, if demand turns, they might have filled up their factory floor with things they will never get any use out of.

Once players have stopped cursing about how they simply can’t fit what they need or that one tile they placed incorrectly two rounds ago, each player gets a small factory floor extension as a piece of hope that next turn’s build might go better.

Selling

After a small admin phase, it’s off to the races: selling cars. In reverse turn order, players can now sell the cars they produce to potential customers (the cars on the market board). A player first takes one of their market windows (thin rectangular frames of plastic) and places it on the board in an area that the dealership fulfils the market requirements for. There is one window for each of the three dealerships of a player and that window comes in three sizes (1×2, 2×2, 3×3) depending on whether or not that dealership is next to advertisement tiles. The player then picks up all cars in a single niche and gets money equal to the selling price of that area. Or they pick a niche in a window they already have placed before.

What’s the selling price? Well, the market board has some diagonal strips of the same background. From the top-right towards the bottom left, each strip that contains at least one buyer gets assigned a value that starts with 6$ for the first strip and decreases down to two. So the more towards the top-right buyers are, the less valuable the rest of the market becomes.

Selling is rather straight forward because the limiting factors have been decided in previous phases: how many cars do your mainlines produce and what kind of stuff do they off potential buyers. However, the order of which player sells first and where is really important. It’s part trying to maximise your own earnings and part taking away what other players could reach. Note that money is just straight victory points and as one never has to spent money on anything in Horseless Carriage.

Expectations & Demand

Once selling is completed, players take back all their sales windows again and any remaining buyers are left on the board for the next round. The older of the two active dimensions is removed and another one takes its place. Which one is decided by the amount of advancement the players did during the research phase. The outgoing dimension however is marked such that the next time it comes in, its minimum requirement is increased by one (so instead of 0-3, customers demand 1-4 of that tech, next time it goes out 2-5).

Finally, players grow demand by selecting a card from a small deck that is available to them and placing it into one of the four quadrants of the market. The card decided which “sparks” (tiles generating new buyers each turn) are added to the board and where. But it also influence how fast the game ends by showing zero to four clocks, each one moving down the marker on the game’s time track. A whole game of Horseless Carriage is usually between 5 and 7 rounds after which the player that earned the most money through sales wins.

Introductory vs Full Game

Horseless Carriage comes with the recommendation to only use a single car type in your first plays. The full game adds two additional car types, trucks and sports cars, which have different mainline tiles and award an additional +$1 and +$2 per sale respectively. While having more car types spices up the market situation (e.g. some players simply cannot sell to certain lucrative buyers because they don’t produce that type of car), I on the other hand didn’t feel anything missing from the introductory game. It just removes one additional dimension of play and strategy but there is still enough to chew on.

So far, sports cars seem hotly contested because their mainline tile is rather small and thus easy to fit into your factory and the +$2 per sell is substantial what with base prices ranging only from $6 to $2. Trucks on the other hand have a giant mainline tile that causes more building problems, but trucks have a higher chance of one player being the only one who can sell them as others didn’t want to bother. Still, the standard car usually comes in bigger numbers and it seems difficult to operate without at least one standard card mainline. So depending on where and what type of demand the players generate, one or the other type of car can be more lucrative to produce.

One particularity of the introductory game is that there are only two mainlines per player. So it can easily happen that someone builds a third and one player is stuck with having only one mainline, something that doesn’t happen in the full game as there are 2 mainlines per player per car type.

Solo and Two Player

As I mentioned, there is no official way to play this solo, which is a shame. The spatial puzzle of constructing your factory in an optimal way is perfect for solo play and the one phase of the game where you want to have as much time as you can. So I actually started developing a solo mode myself which can now be found on Boardgamegeek. It’s still in an early stage but works quite well already. It can also be used as a third player in a two player game, opening up the game to a larger potential audience.

However, the spatial puzzle part is not the central part of playing Horseless Carriage. It’s the meta game of influencing demand and research such that your opponents have problems fulfilling the market requirements. The factory puzzle is just a means to an end. So for the full experience, three or more players are definitely needed. Still, having the capability to play solo allowed me to dig deeper into the game and see what consequences my actions have.

Production Oddities

While wether or not the art direction will be to your liking is a matter of taste, there are a number of production issues that are worth mentioning. For one, the initial print run had some of the arrow pieces mixed up and there were no yellow/blue for certain categories. Splotter now kindly provides a “fix sheet” for free that adds the missing cardboard pieces. Unfortunately, on some of those replacements arrows, the label on the reverse (indicating the dimension/color of the arrow) is incorrect. It’s an unfortunate mistake, but I typically play with the non-label side anyway. For people with impaired colour perception, it might be an issue though.

There are also some inconsistencies that most players won’t expect from a modern game: some of the technology tiles have slightly different shades of grey although they belong to the same category (letter / background pattern). Also my red market windows have a slightly different shade of red between the different sizes. There is nothing game breaking, but still it feels odd for a game that costs 100€. One thing to keep in mind here is that Splotter is a very small, independent publisher that brings out new games rather rarely. This is not an operation where anyone gets rich or could even sustain a living from it but rather a labor of love. It’s thus even more commendable they offer the fix sheet for free. In the end, with the fixed arrow tiles, I don’t mind the rest.

On a positive note, I really love the slightly glossy cars. It’s just adds a certain something. Two things could seriously benefit from an upgrade: it would have been amazing if the dimension boards were dual layer (because one picks them up and moves them in and out of play with tokens on them) and I would pay serious money if the market windows weren’t thin, easily bent plastic but instead metal. The main board is larger than it needs to be and I think the tracks should have been separate side boards or integrated around the market. But overall, I like the look off the market with the tiny cars, sales windows, sparks, etc. The factory with all its grey is something I struggle more with. While the illustrations of the parts themselves are nice, using hatched background patterns and shades of grey to indicate their category has a definite Windows 3.0 (yes, the one before Windows 95) vibe.

The elephant in the room here is what a lot of reviewers point out as the “fiddly-ness” of the game. In your factory, there are so many tiny cardboard pieces, a single brush or bump easily moves everything. The dimension cardboard tracks need to be moved in and out of play with tokens on them that all too often slide off them. Placing sales windows on the markets and taking them off often involuntarily moves sparks or cars. This is all true. The thing that most reviews I saw didn’t mention is that in the vast majority of cases, this might be annoying but has little consequences. In all my plays, I was able to reconstruct the original state without a problem. So I wouldn’t necessarily describe it as fiddly. It’s more the nightmare of anyone with OCD with no chance of keeping things straight. It’s not great, but it’s workable.

Conclusion

Against all odds, I simply adore this game. Yes, the factory puzzle fries your brain and produces a long, silent, heads down phase for all players that is only interrupted by the occasional cursing. Yes, there are production errors and no official way to play solo. Yes, the artwork is – let’s call it – sparse. Yes, it requires a minimum of three players. There are many reasons not to like this game. But at the end of the day, it has an irresistible fascination to it that keeps me thinking about it and gives me the feeling I will want to keep playing it for a long time.

With the amount of new games I’m playing each year, there is a constant flow of games coming in and being sold off again not longer after. So it’s kind of remarkable when a game manages to secure a place in my collection so quickly. Horseless Carriage manages to do so because it does a number of things different than any other game. For example, during the build phase of the very first turn, you have to plan ahead what and how you will build for at least the next two turns AND also account for unexpected changes. Any slight mistake you make will have dire consequences later in the game and in a game easily lasting 2-3 hours, that’s not a chance you will want to take. On the one hand, this is a huge problem because the game just started and kind of grinds to an immediate hold. On the other hand, Horseless Carriage rewards you for clever planning like few other gains. The small margins for errors also open up huge possibilities to indirectly screw over your opponents, for example by pushing for a dimension that they literally have no space for placing new technology tiles in their factory.

As drastic as in few other games, Horseless Carriage makes it clear that it is all about player interaction and the meta gaming. Pushing research, building factories, order of sales, they are all just necessary skills you have to master to be able to play “the real game” about long term demand, flexibility to adapt your factory to changing market situations, which car type to push and which not, etc. For example, while new players might intuitively invest in lots of research departments and thus influence demand, the more you play the less it becomes about the research you do yourself but the timing when to spent your Gantt charts and become first player, utilising all the research other players have done. But having more research allows you to turn the market and push for demand that no one else can satisfy. Or the question where to generate demand: it can be used for maximising your own profits or to drop the price of areas your opponents can reach. Do you invest in the most likely dimension to become active next round or wait until your opponents have used up their factory space and then push for a dimension they cannot deliver in?

The only other game that comes to my mind that did it to this extend is Curious Cargo which starts out as a cute looking pipe-tile-placement game. After 10+ plays, that part becomes second nature and fades into the background as a dance between both players ensues about pushing here and pulling there, acting on mistakes your opponent makes while staying on your toes yourself. “Advanced” Curious Cargo is such an enticing game, but hardly anyone will ever play it to that level because the initiale pipe-tile-placement already loses most players. I’m kind of afraid the same thing is happening with Horseless Carriage and I’m wondering what percentage of buyers have actually played it more than two times before coming to the conclusion it’s not for them.

In a lot of ways, the interaction of game mechanisms is amazing and small nuances can have incredible effects. It’s also refreshing that a game this complex comes with so relative few rules. The biggest problem I see is the build phase: even when done in parallel, it takes quite some time to find a good arrangement of tiles. However, technology tiles are limited and it can in rare cases happen that a player finishes their build but then the player that is in front of them in build order says “sorry, I need that tile” and takes it away. I haven’t had that happen in my plays, but it’s something I’m afraid of. Even more severe is this effect when playing with all three car types. The decision which car types to produce is so influential that to play optimally, one almost would have to wait for the previous players to finish their builds and only then pick which new mainline to add. E.g. if you are last and know no one has build a truck mainline and everyone went for sports cars, that will influence your decision whether you add a sports car or truck mainline. In reality, I haven’t had the chance to play Horseless Carriage multiplayer that often that people would have been so competitive. But again, it’s something that I kind of dread happening at some point, slowing down the game even more. Or if you would see that other players cannot reach a certain segment of the market, you might want to leave out some tech tiles you planned on building and instead push in that direction. So from a game mechanism perspective, it should happen one after the other, but from a game experience level, it should be “heads down and don’t look what other players are doing”. But if it is the latter, why limit the number of tiles? It kind of feels odd in such an otherwise clever design.

To sum it up, my recommendation here would be “know what you are in for”. If you don’t like spatial puzzles or don’t like having to plan multiple turns ahead, this won’t be for you. This is not a game to break out and “just have fun”, it’s a challenge. It’s punishing, it’s long. But it also packs a lot of juicy decision in a surprisingly small set of rules and does things different than other games. I never quite clicked with Food Chain Magnate, but this game struck a cord with me. I really enjoy my plays of it, especially so now that I can play it solo, get way more plays in, and explore the meta game and the consequences of my doings. I also enjoy following online discussions about building techniques and various strategies as they give a taste of what is yet to come for me. It’s early in 2023, but I’m quite certain Horseless Carriage will end up in my top three games of the year. A fascinating game, but unfortunately not for everyone … or even most.