I usually don’t do previews. Heck, I’ve even kindly declined designers who wanted to help me out with review copies. After all, writing about board games is a hobby for me and I fear more the pressure of having to write about some game I might end up not enjoying than having to waste my own money on it. I’m making an exception for World Order though as it has firmly planted itself in my brain ever since I—by chance—met Vangelis of Hegemonic Project Games at SPIEL 2023 and he told me they had been working on a sub-2h game about international politics. As someone who has been interested in the international system for a while and just came off GMT’s Mr. President (which was way too long and convoluted for my taste), that was sweet music to my ears.

A lot has changed since then. Feedback from fans of Hegemony has led the two designers to beef up World Order in regards to complexity, a successful Kickstarter campaign has convinced almost 11,000 people to back this game, many playtest sessions resulted in various tweaks, and … oh well … the international system as we’ve come to know it has been shook to its core. This made me all the more curious to see if a game about international politics set in 2010 would feel frighteningly timely or already out of date.

So I reached out to the team and asked if they would kindly let me borrow one of their prototype copies. And they agreed!

Disclaimer: The Current State of The Game

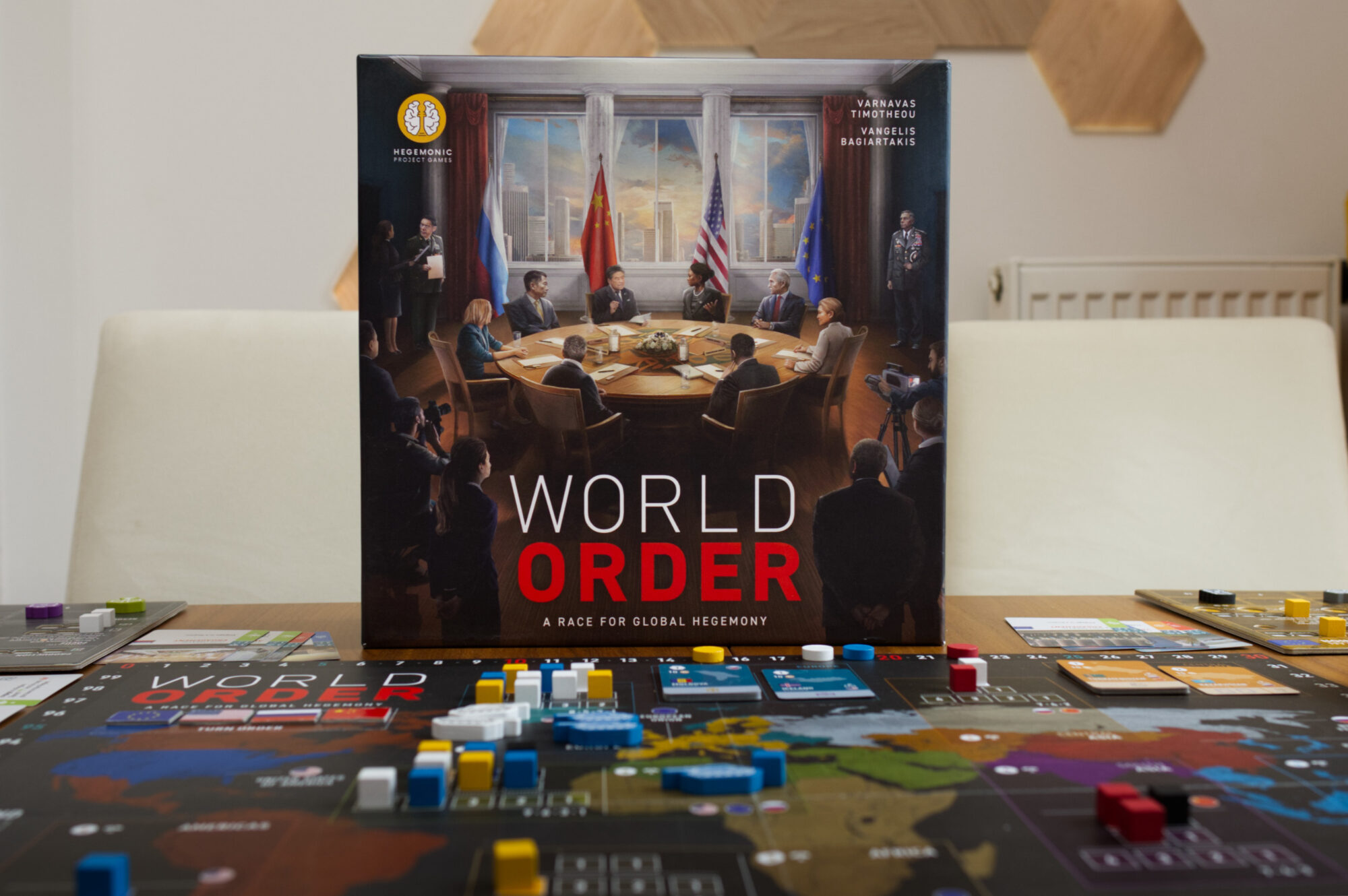

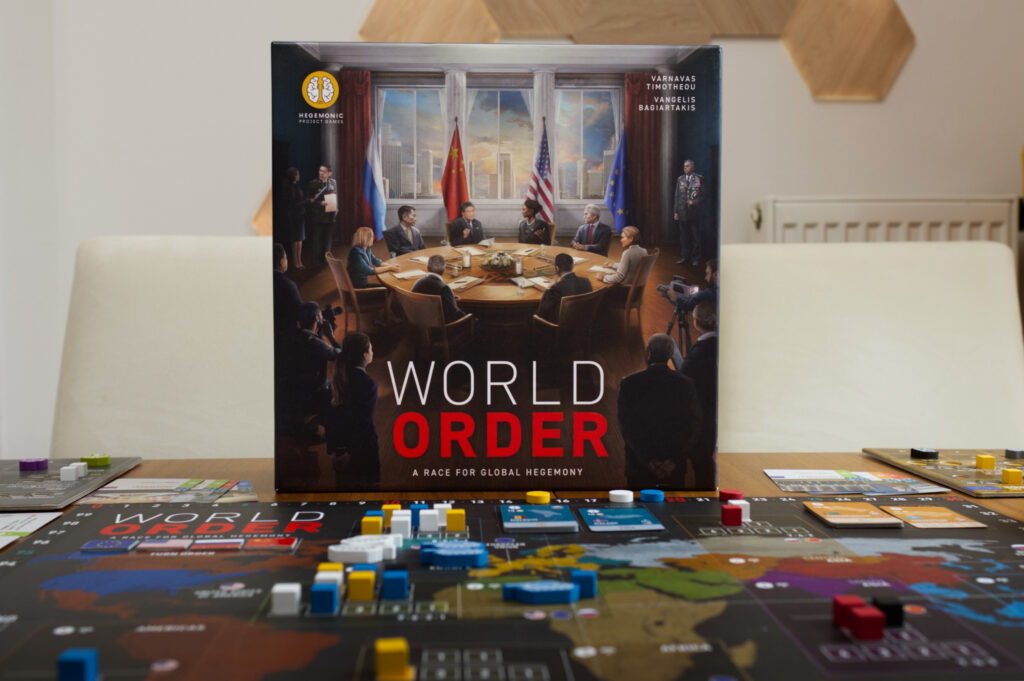

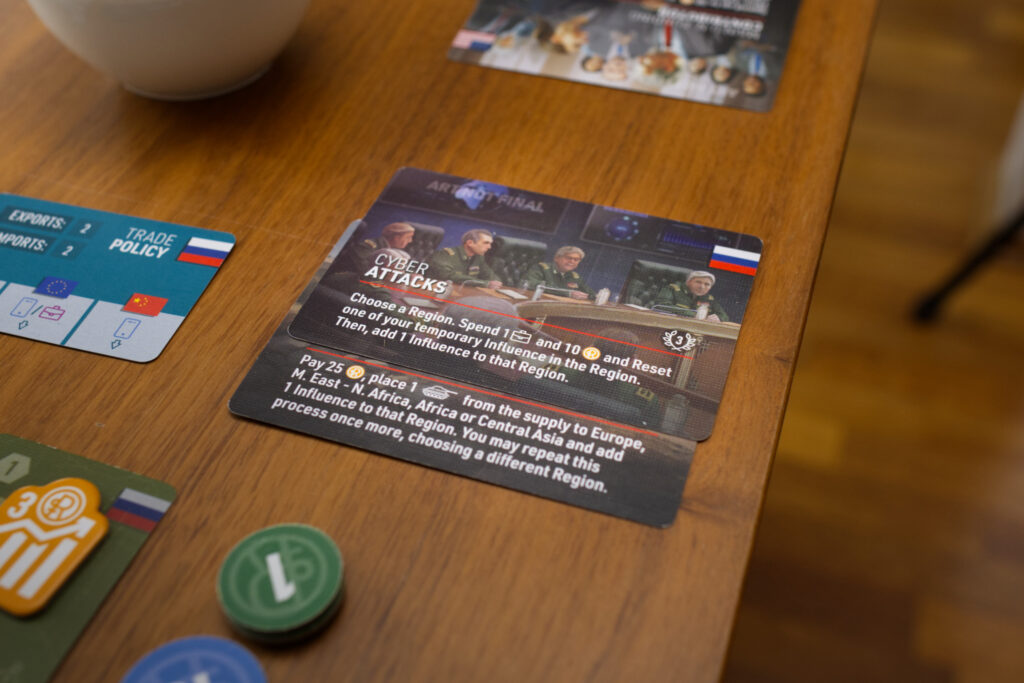

First of all, I have to stress that this game is still in development and all components shown here are potentially subject to change. To be precise, this is the version that went out to content creators back in Nov 2024 when the Kickstarter campaign launched. If it weren’t for the “art not final” printed on some cards though, the obviously cheaper card stock, and the fact that the turn order track has been stickered over, you wouldn’t know this isn’t just a normal retail copy. It just looks great! I mean there are even screen-printed army tokens for crying out loud, and just look at all that beautiful artwork. It makes you wonder how companies manage to make even prototypes look this good nowadays …

I‘ve used the recently released v0.5 version of the rules for all my plays but of course wasn’t able to port back all the small component and balancing tweaks that have been included in the Tabletop Simulator version by now. And there surely will be more improvements to come before the final release. So I won’t go into my usual level of depth in regard to balancing but rather focus on the bigger picture: How does World Order really feel to play? To what type of player and groups will it appeal? And how do the educational aspects and asymmetric powers play out this time? Let’s find out …

Setup

One thing that always deters me from games is a long, involved setup. Having to throw out components based on player count, sorting tons of tokens, that kind of stuff. World Order is pleasantly simple in that sense: a reasonably sized (as in non-crowdfunding-oversized) main board is placed in the centre of the table, some small-format decks representing potential allied countries are shuffled, a couple of initial cubes representing influence are placed on preprinted positions, and the main board is done. Shuffle the deck of available-for-purchase action cards and create a market display. Hand each player their dual-layer player board, a couple of resource marker tokens, a supply of generic cubes/army tokens, and some initial money, and that part is also complete. Depending on the global power players will embody, they will get a slightly different starting deck of 12 action cards, a few countries they are already allied with, and some “strategic assets”, special one-time actions only they can do.

There are a few other elements but the gist is: while there is a lot going on and you will need considerable table space, setup is rather straight forward and no trouble at all. We’re off to a good start.

The Teach

With Hegemony, there were two main things that seemed to keep players from diving into it: its substantial play time (which made it more of an event experience rather than something one can pull out on a given weekday) and having to explain the game basically four times, as each class had their own substantial amount of rules on top of the shared core ruleset. In comparison, World Order is a much easier teach. There is one ruleset for all and each individual action in itself is rather straight forward, too. Want to get a new ally? Play an action card with the term “improve relations” on it, pay the country’s cost in “diplomacy” as printed on the card, potentially get a bonus if you have a card of the same country already, done. Compared to the substantial dilemma players will be facing in deciding which of their cards to play and in which particular order, doing the actual actions in themselves often feels like a big “wait, that’s already it? I guess I’m done, you go”. It’s like the rules get out of the way quickly and you’re left with making some hard, really hard decisions.

Learning the rules of World Order is thus much smoother than for Hegemony and thanks to some nice player aids, there is rarely a reason to consult the rulebook. However, there are some nuances that might not be apparent on first play. For example while the “move” action allows players to move an army token from anywhere to a new location, moving as an implicit part of the “build base” action requires the army to come from the player’s personal board and not be already on the main board. Or understanding why there is a distinction between “produce” and “train”. But we found nothing that would have spoiled the experience of a first play for us.

Looking at setup and teach, I’d say it takes about 45min if at least one of the players has played the game before. The rulebook is still being updated and improved, but I’d say it’s already pretty nicely structured and easy to read, with the rare ambiguities we found coming rather from the card texts themselves, which likely have already been improved (remember: the components in my version are already half a year old!). As with many heavy games, there is the typical initial moment of disorientation, having understood the rules but not quite being sure where to start. On a second play though, players already approach things noticeably differently and with a much clearer focus and purpose.

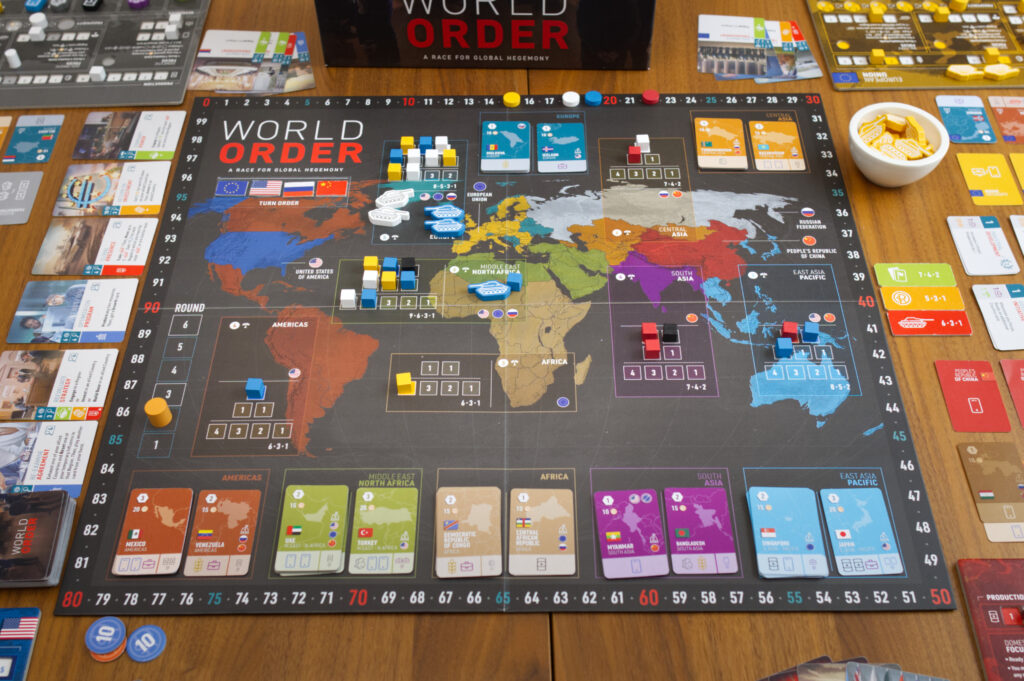

Game Structure

Conceptually, World Order is a simple game that has been layered to give it more complexity and depth, like adding more colours to a palette to be able to paint a richer picture. At its core, it is an area majority game about gaining influence in 7 regions around the world as represented by slots and cubes on the main board. Each region has a number of permanent spots that once claimed cannot be lost as well as a number of temporary slots where players can get pushed out in a convey-style way. If someone gains influence and there is no spot let, the oldest (=left-most) cube on a temporary spot is kicked out. While temporary spots are more dangerous, they come with a non-trivial amount of immediate VP simply gained by claiming them.

After the 3rd and 6th round of the game, a special scoring phase is done where VP are awarded based on majority of cubes in a region with armies potentially acting as tie breakers. Although there are other ways to gain VP, being able to score regions is vital and therefore the main motivation for all the global powers. You might end up with the biggest army or the biggest production of goods, but that won’t win you the game in itself. As a result, much of what players will be doing are actions that either directly or indirectly will allow them to place new influence cubes onto the board. It’s like an area majority game that is fuelled by an efficiency puzzle which in turn is fuelled by a Dune Imperium-style deck building game, but everything squeezed into just six tight rounds.

There is a trinity to World Order, three separate paths to gaining new influence that are all interwoven: domestic (=economic), diplomatic, and militaristic. Each has a single type of action that can be used to place a new influence cube (investing in an ally, engaging in a region, and building a base respectively) and all three of them need something to fuel them. Take for example “investing”. To start with, one needs an ally country one hasn’t invested in already as every ally can only be invested in once. Then one of course needs the right action card on their hand to trigger the action. And finally one needs money to do the investment itself, which is usually gained by selling goods. Gaining allies and trading goods are two of the other types of actions and thus require cards to be played as well plus resources to be spent. So placing a single influence cube can be a multi-turn process if done inefficiently – or – one can try to sell enough goods to maybe be able to do two or three investments before requiring more money again. A lot of World Order anchors around this type of action efficiency, and for that of course purchasing improved action cards from the market becomes important, hence the deck building aspect of World Order. But more on that later.

The other thing to aim for is preserving military dominance in one’s own zone of interest, a fixed set of regions marked by one’s own flag on the main board. For example, the US is primarily interested in the Americas, Europe, the Middle East, and East Asia. The EU on the other hand is interested in Europe and the Middle East, but everything else isn’t an immediate priority. This has two effects: one, without military bases, a global power can only deploy armies within their own zone of interest. Two, at the end of each round, a player loses 2VP for each faction that has more army tokens than themselves in a region that is part of their zone of interest. This is called “threat”. If not acted upon, one can easily lose 4-6VP every round to threat, which is quite dramatic when winning scores seem to be in the 100-120VP range and the leading player often will only be ahead by 10 points or less.

So players are interested to at least tie other players for military presence and gain as much influence on the board as they can. But how to achieve all of this?

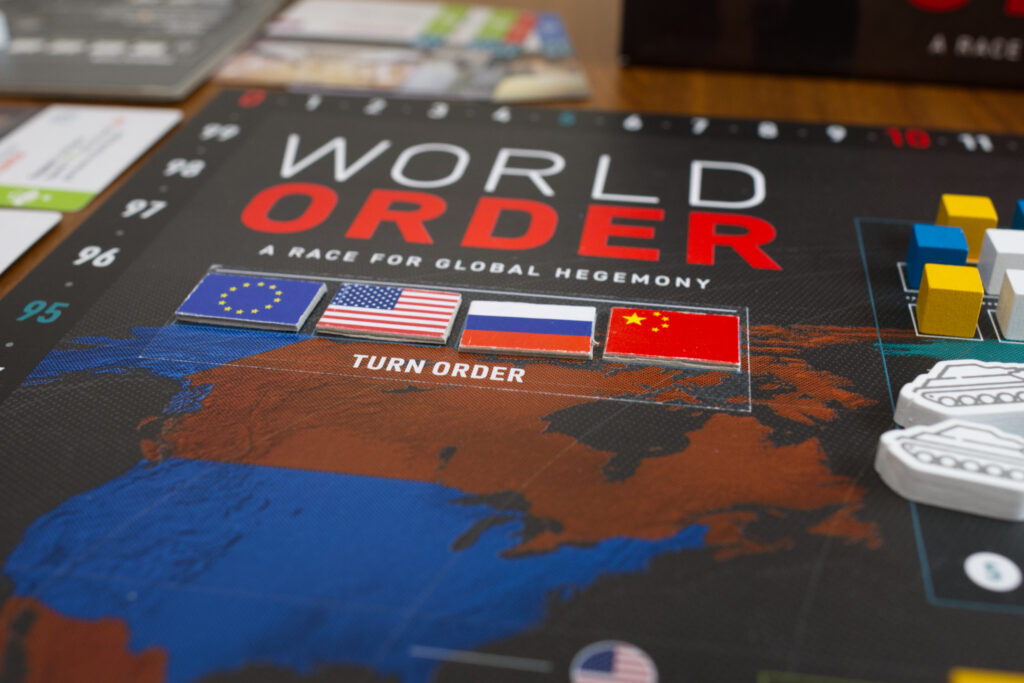

The Turn

Each of the 6 rounds starts with a general preparation phase. Most of it is fairly standard fare and can be done in parallel, like drawing a new hand of 6 cards, cycling which allies are up for grabs that round, and increasing one’s own amount of oil, raw materials, and food (collective called the “primary resources”) by whatever production level is indicated on a player’s board. There are two key decision points here though: first, in increasing order of current victory points, players choose their spot in turn order. For some aspects like picking new allies or choice spots of influence on the map, being first is better. For other things like end-of-round majorities in armies, being last opens up huge possibilities for causing trouble. With the full four players, I often found myself wanting to go first to be sure to get what I needed, while with two, being last seemed more attractive to be able to swing majorities in my favour.

The even more critical decision is what personal focus to choose for that round: domestic, diplomatic, or militaristic. This is one of the major additions that was made to the initial sub-2h version of World Order and while it adds playtime, it is also one of the most interesting decisions each round. Domestic is great for resource production and buying new cards for one’s deck, diplomacy is great to get new allies which can be helpful in a multitude of ways (more on that later), while military is one of the few ways to produce new army tokens. Each focus is basically an active choice to NOT produce something else and each comes with a bonus that might be helpful for that particular round. Like having +1 threat when choosing the military focus, which doesn’t sound like much but can severely shake up the balance of power on the board. It’s hard to describe, but I actually found myself getting into a good flow of choosing what action cards to play and plan my round rather quickly but still struggle to figure out what focus will serve me best in a given situation. A lot hinges on that simple decision.

The actual main part of the round is simple in structure: each player starts with 6 cards and can play four of them for their action, one at a time. The remaining cards are revealed in a Dune Imperium-style way to give the player additional money and card purchasing power. In contrast to Hegemony, there is no carry-over of cards to the following turn, which can be agonising. It happens surprisingly often that one comes up with a well-working sequence of actions that would utilise the current board state perfectly, but then there is that one card that is just too painful not to play. Like being the Chinese player who only has a single “build base” action card in their starting deck and then having to let it go, possibly taking two or three more rounds until it will surface again. Luckily, these kinds of issues can be mitigated in a sense.

After all players have done their fourth action, they can purchase new cards from the market in the “research” phase. The obvious question is of course how this works out in a game that has just 6 rounds. The answer is: quite well. Of course it’s not deck building to the level of a Dominion where one is cycling repeatedly through the deck and any purchase comes up over and over again. There are also only few ways to cull a card from the deck, making the deck grow one or two cards with every round. Instead, newly purchased cards are placed on top of the personal deck, ensuring they will go into a player’s hand in the next turn. Purchasing new cards thus has two effects: for one, it is a way to make sure a certain action type will definitely be part of your hand next round. E.g. if you know you’ll need a trade action, it might make sense to pick one up even though there might be more interesting cards in the market. But even if the immediate use isn’t the primary motivator, the purchasable cards are typically stronger versions of the ones in the starting decks and you’ll typically see your new purchase 2-3 times during the course of the game, which can have a noticeable impact.

The last phase of a round is called “aftermath” and it is where in addition to threat and scoring a few other admin things will happen. Players get income in the form of money from allies they’ve invested in, which is a welcome bonus but more a side effect of using the invest action to place an influence cube. It’s also where engage tokens can be converted into money or temporary threat defence. This is a rather recent addition to the rules to bolster the engage action (the diplomatic way to place influence) as before it felt a bit weak as an action. I’m not quite sure what to think of this part of the game yet. On the one hand, engage tokens on occasion have saved me from losing points to threat and it is a nice incentive to collect more and more allies from the same region as a single engage token can be converted into 5 coins per ally card one owns in that region. But I have the feeling a slight tweak to the rules might make engage tokens into something that players actively will want to get instead of just a nice thrown-in of the engage action.

Import & Export: Trading Resources

One particular element I want to highlight is how trading is implemented in World Order. Each power has a small card showing how many import / export transactions they can do and what they can trade other players for. Well, trade is actually the wrong word here. More like involuntary selling.

For each available transaction, a player can choose one type of good (yes, even armies). They then check how many symbols they see on their ally cards and that’s the available market they can export to in order to earn money. Primary resources that are automatically produced each round earn less money while secondary resources (=luxury goods, services, army tokens) bring more but only get produced if the respective focus is chosen at the top of the round.

Importing works in a similar way. Some (but not many) of the ally cards have import symbols on them which means one can buy goods from them. In addition, each global power has one or two goods one can purchase from them. The US sells “services”, China “luxury goods”, the EU can sell either, and Russia oil or raw materials. The number of items available for purchase again depends on the number of symbols printed on the card, in most cases just one.

So you might be wondering: Why should a player even hand money to a competitor? For one, they get to increase their “diplomacy” resource, which is useful to get more allies, and two, other players might be the only reliable source to get that resource from. Take for example oil. As the EU, your starting production of oil is 1. Yes, just one! Oil is needed to produce luxury goods and services, both of which have many interesting applications. So the EU has three choices: try to push its own production, but that maxes out at 2. It can acquire new allies that are willing to export oil, but those are rare. Or it can trade with Russia. From the perspective of the Russia player, there isn’t much to lose by doing this deal. They get money (which they desperately need) and usually don’t even have to reduce their own oil marker for it. The reason is that each power has two commerce cards that represent overproduction and can be flipped to basically generate a free resource that’s just for trading. The only downside is they will have enabled the EU player to do something with that resource they otherwise couldn’t have.

The trade action feels strange but interesting. Being limited in what you can buy and sell by the icons on your allies gives a great incentive for diplomatic activities. The strange—or rather unfamiliar—part is that even if a player has a lot of resources (say oil) in their supply, they can only sell a single one to a given player because the trade card only shows one icon. It feels similar to how there is military in World Order but no form of combat. Trade here is the major source of income and an enabler for other actions, but not free trade as in “let’s make a deal”. Overall, I like it. That focus on being screwed if one didn’t improve relations with the right allies feels nice.

The Importance of Allies

Speaking of allies: I like how the allies are interwoven into pretty much everything. Getting a new one doesn’t give you anything by itself except that ally card, but it is an enabler for lots of other things to come. Without the right allies, your ability to import/export goods will be severely limited. Without allies, you won’t be able to build bases or invest in them, taking away two out of three ways to get influence cubes onto the board. Without allies, engaging (the third way to place a cube) will be prohibitively expansive as allies can be exhausted to lower the price of “diplomacy” needed to engage in a region. You can use allies to pay for improving relations with other allies, use allies to get more “research” points for buying new action cards at the end of the round, and so on.

There are multiple actions that require a player to exhaust an ally (=flip the card over) and they don’t refresh automatically at the start of the next round. Instead, the number of allies to refresh depends on the focus one chooses, and can be as low as 1 or as high as 4. So similar to triggering a certain type of production by choosing the respective focus, allies are a currency that can be spent and refreshed, but refreshing a large amount of them means to choose the diplomatic focus and not do something else.

A nice late addition to the rules is the special rule of getting an influence cube when receiving an ally card for a country one is already allied with. It just feels super satisfying, even if for many purposes it would be better to have one more different country on your side.

Game End

At the end of the 6th round, after the second scoring is done, the game ends. Whoever has achieved the most victory points has won. Besides influence and threat, there are a few more sources of VP. At the end of each round, players can convert the luxury goods into prosperity of their population which provides both VP and money. One type of card action I haven’t even talked about is “growth”, which allows players to buy increasingly more powerful so called growth cards, sort of an optional tech tree. There are some nice abilities in there like being able to trash (=cull) cards or draw more of them. The highest level of growth card comes with no ability at all but a very healthy amount of VP, making investing in growth cards interesting just for the VP alone.

Also as part of scoring, the players with the most ally cards, army tokens, and current money will get a few extra VP. None of this provides so many VP that one could drop the ball on the area majority game, but they are a good incentive to branch out into one direction or the other.

Asymmetric Player Powers

The aspect of World Order that will likely have the biggest draw on potential buyers are the asymmetric powers and restrictions of the different global powers. It’s what makes World Order stand out and more than just another hybrid area majority game. I’m fascinated by how World Order tackles having each power play like its real world equivalent without requiring a large set of specialised rules or forcing players’ hands too much. In fact, just looking at the rulebook, there are only three small additions that are specific to global powers: during scoring, the US player needs to have majority in influence in a large number of regions to not lose VP and the Russia player will need to have military power in its zone of interest. Otherwise the EU and the US are under NATO and therefore do not cause threat for each other. That’s it. Those are the only power-specific rules in the whole game! Everything else is embedded in the starting deck, symbols on cards or the main board, and the respective player boards.

The most telling example of this was when I had my first short demo session at SPIEL Essen 24. After going through the rules teach, all four of us were initially focusing on our own problems and figuring out how to get the ball rolling. We had been told each power’s starting deck had a slightly different composition, but otherwise it seemed like we all faced similar issues. I mean how could we not? We were all playing by the same rules, right?

But then we noticed that the EU for some reason kept buying oil from Russia and the US player didn’t like it that all that money exchanged hands. China was ramping up its production in a scary way and the EU seemed to pick up allies left and right. We had to laugh as we realised how the game had nudged us down a path that felt all too familiar, reminding us of news segments from just a few years ago. And we hadn’t even noticed it. It’s moments like this that make World Order come to life. Like when you look up from your board and realise that your oil production will max out at 2 per round even if you upgrade it while another player’s starting production is already at 5!

There seem to be multiple aspects that steer each global power down a certain path. Take for example building bases. As a reminder: without bases, one cannot deploy troops to a region unless it is part of the zone of interest as printed on the board. But only if one has seen what ally cards exist does one realise its difficult to almost impossible for certain powers to gain a foothold in certain regions. With it comes also the realisation that one doesn’t need troops everywhere. As long as one has enough in one’s zone of interest to not get penalties, one is usually fine.

Then there are the differences in the starting decks. The US only has one invest card but two “build base” while China has a whopping three trade cards but only one build base. The EU on the other hand, true to form preferring diplomacy to military, has 2 engage and 3 improve relation cards, so more diplomatic actions than anyone else. Or compare the 30 coins starting money of the US with the lousy 15 of Russia. It’s things like that which make players feel like they are playing the same game (=influence & armies) but their path to achieve victory will inevitably be different.

As a result, World Order doesn’t produce the almost role-playing like situations of Hegemony with its highly specific decks and evocative flavour texts. It feels more like a gamer’s game, a system where player’s are curious to shake things up and see how things play out if they do X instead of Y this time. It definitely has gotten me thinking. At one point for example, I was playing a two-handed solo game to learn the rules and was literally thinking “thank god there is NATO, otherwise I would be in deep sh… right now”. It’s small moments like this that made me pause and reflect once again on what’s going on in the world right now. How would World Order play if the NATO rule wouldn’t be there? I have high hopes for the “World in Turmoil” expansion (which was part of the campaign) and will add actual historical events. While it will be challenging for the designers to implement those without breaking the game’s balance, I think it will be super interesting to play with those and explore what happens.

Player Count & Play Time

Finally, let me talk a bit about play time and player count. There are surprisingly few changes when playing with less than the full set of four players. A small deck of cards manages how the non-player powers compete for influence and threat, and some cards get discarded from the market, that’s it. This works well, is super low overhead, and I’ve enjoyed my 2p plays. However, we noticed how it turns what at four players was a highly dynamic tug of war that could on occasion turn into a bit of a negotiation game into something that at times can feel slightly multiplayer-solitaire. The 2p game just developed—for our taste—too much of a tick-for-tock rhythm between the players that lacks the chaos and excitement of the four player game. The efficiency puzzle comes more into the foreground and the area majority struggle takes a step back. Still a very good game, but at higher player counts it’s a great game.

It will be interesting to see if the not yet released solo mode will be compatible with playing with two players. It would mean a bit more admin than the simple auto-influence cards, but it might spice things up just that little bit the two player experience needs. Concordia Solitaria is a good example how much fun playing against a competitive bot can be. There might also still come some tweaks to the rules for 2p, who knows. For example, it felt to me that the cycling of which allies are available in a given round was a hair too slow with two players and therefore the luck factor of the right ally coming up or not intensified. This could easily be changed by cycling not one but two cards per round in each region. But to stress it: I very much enjoyed playing 2p with the rules as is and would happily do so again.

Small FYI if you’re interested in playing World Order predominantly with two players: not all combinations of powers are valid when playing with two players. One player has to choose EU or US while the other has to chose China or Russia.

As to playtime: my 2p game lasted 2 3/4 hours, though it has to be said we were both enjoying thinking through and discussing the various options. After 3-4 plays, I think it would be possible to get it done to two hours if both players pushed it a bit. On the other extreme, my first 4p game lasted for over four hours, not including the teach! Mind you though that we all felt World Order was what we Germans call “kurzweilig”, like we were totally engaged the whole time and it felt nowhere near as long as it was in reality. If we wouldn’t have spent so much time discussing potential moves, we probably could have shaved off an hour. Nevertheless, as a 3-4p experience, I’m afraid the game length will push World Order more into the “event” category again. The big benefit World Order has over Hegemony though is how easy it is to get back into the rules, which is why I see a much higher chance to get it to the table semi-regularly than for Hegemony.

The Concepts Booklet, Stretch Goals, And Other Kickstarter Things

One of the things I enjoyed most about Hegemony was the concepts booklet that came as part of the Kickstarter version. It gave some background explanation about the fundamental theories underlying the game and something similar has been done here again. The concepts booklet looks gorgeous with nice full page art and is written by different academics for each power. One thing I noticed though is that after a general section it rather discusses power by power than to continue discussing the international system as a whole. Personally, I would have been more interested in the latter, but going in-depth for each power of course makes sense to catch those players up that might not already know for example what the EU’s motivation and struggles. Overall, I was super happy to see that it was already included in the prototype copy and I thus had a chance to read it. It really is a nice part of the World Order package that helps bring the whole thing to life. Not necessary, but the proverbial cherry on top.

While I’m at it, you might be wondering what I pledged for myself. I chose the non-mini, all-gameplay version and added the metal coins. While the minis look great, I think having abstract army tokens works better for the academic character of World Order. Also as someone living in Central Europe and thus not that far away from an active war zone, having realistically looking tanks would feel off to me. As for the metal coins, regular readers will know how much I like having those and the ones for Hegemony were pretty sweet, so I of course backed those as well! The hard-cover version of the concepts book had me tempted, especially since I was able to hold it in my hands at SPIEL 2024, but the soft-cover has the benefit of being able to fit more easily into the game box.

As for stretch goals, I’m really looking forward to try the solo mode and the objective cards. I always appreciate it if a game adds those, not only for replayability but also to give new players something to aim for during their first plays. Having more variety in growth cards will also be great.

Conclusion

Hegemony has been a huge hit for publisher Hegemonic Project Games. It’s reached the BGG Top 50 by now, an accolade that is truly deserved for being innovative, fun, challenging, and educational. It’s a masterpiece, something that keeps players wondering how the designers managed to make it work at all, let alone this well. At one point, there were simultaneously separate BGG discussion threads going on for every single class, claiming that that one was obviously overpowered and the others had no chance to win. This must be a bucket list item every board game designer is hoping to achieve one day.

While deserved, the high ranking also came as somewhat of a surprise to me. Judging by my circle of friends, I know no one—except me—who would be eager to get it to the table right now. They all appreciate it, they all had fun playing it, but the substantial rules load and playtime unfortunately turned it into an occasional event instead of something we would get off the shelf regularly. It’s like a Twilight Imperium, something to specifically carve out time and plan for. So when I heard that World Order had gained in complexity and playtime to be more in line with Hegemony, I wasn’t sure if that was really the right way to go. Longer playtime often means less actual plays and less people willing to learn a game.

Fortunately, these fears have been unwarranted. Yes, it’s big, and yes, it can take 3h (or more) to play. But the rules teach is so smooth, it’s like slipping into a glove if you have played any modern Euros at all. I play a lot of heavier games, and one thing I have come to dread by now is opening up a box for the first time and seeing the rules are like 30 pages, there are tons of different components, and everything feels like an incoherent bashing together of more and more mechanisms to create some form of complexity. In contrast, World Order’s rules are like 20 pages, and that includes some gorgeous full page art and large example sections. If Splotter Spellen would have laid them out, it would probably have been just 6-7 pages.

Things just click with World Order. You hear the rules and think “alright, got it, alright” … and then get hit by a wall: what to do now? I still remember that first demo session and how I thought that I had understood the rules but had no clue what I wanted to do on my first turn. Sure, get influence cubes on the board, but what would be a good action and what an inefficient one? What new cards would I need to buy for my deck, or would I need to get those at all? It felt a bit like sitting in front of a go board for the first time: I get it, but I still don’t know where to place that first stone. I think the reason for this is because World Order appears so “open”, like it’s teasing you “just play a card, try stuff”. You can do diplomacy, you can sell stuff, you can train military, none is obviously better than the other. But on closer inspection of all the information that is encoded on the player boards, main board, and in the cards, it becomes clear that not all things are equal.

Take for example the regions of the world. Your pre-defined zone of interest definitely needs to be a point of attention to avoid losing VP to threat induced by the other powers. It’s also where you can start to deploy troops immediately. If you want to do so anywhere else in the world, the right ally card needs to come up in the market so you can build a base in that region and if it does come up, you need to be able to get it before someone else grabs it. If Russia for example wants to have a base in the Americas, it better hopes that Venezuela or Cuba come up as those are the only two allies in that region that allow Russia to build a base. If the US player on the other hand wants to prevent exactly that, they can simply make those two their own ally and block the Russia player out completely. No ally, no base. No base, no army. It’s that simple.

It’s soft limitations like this that put players on a certain path that is pre-described for each power. But make no mistake, there are no guardrails or flashing lights that try to keep you on that path. It makes sense for the China player to ramp up their production simply because they start with three trade cards already in their base deck. But based on the situation on the board and the cards that come up in the card markets, it might be opportune to do so less aggressively in one game and more aggressively in the next. Similarly, it might make sense to deploy armies outside your zone of interest just because another player failed to do so themselves and you know it will cost them VP every single round for a while before they can do something about it.

The best way I can describe it is there are two teaches happening: the rules tell players what’s possible and their first playthrough will tell them what’s impossible – or rather hard, few things are truly impossible in World Order. On first glance, World Order might look like Risk, abstract regions that provide VP with few aspects to distinguish one from another. But instead, it’s rather like 4 maps or world views overlayed on top of each other. For example, the US, Russia, and EU all are interested in the Middle East but China has very little incentive to get involved there … unless the other players have so little influence there that the China player might sneak in and grab those scoring VP.

It’s a fascinating approach to player asymmetry, putting players on what at first appears to be such equal footing. This is one of the biggest strength of World Order. It doesn’t judge, no one is “the villain” or “the good one”. As in real world politics, every faction just has their own motivations and—even more importantly—constraints they are acting under, and playing those out helps create understanding. Not understanding in the sense of acceptance or approval of what someone else does but in the sense of realising why they are doing it. It’s a fragile system where actions of one faction have consequences on the actions of another. When it comes to this aspect, I wished World Order had even more things like the NATO rule in it, strings to pull and play with. Of course that would make it less approachable and ultimately end up with a beast like the aforementioned Mr President that tries to simulate everything. So moving complexity to the historic events of the World in Turmoil expansion makes a lot of sense. I have no information on what that expansion will really be like, but I hope it will allow players to take the core system of World Order and say “what if?”. What if there is a refugee crises? What if one of the leaders declares a dictatorship? Tariffs? What if …?

I think the biggest compliment I can make World Order at this point is that I don’t really have any criticism for it. I have lots of ideas, but not anything where I would seriously fault it. The prototype I’ve been playing is already a nice package that I would be happy to play at least a dozen times more. Sure, there are some minor usability things I spotted that could still be improved or wording that could be clarified, but it just works and is fun to play. And there are 1-2 things where I feel the balance isn’t perfect yet, but it’s so damn close that I’m certain either it’s just the meta of my play group that’s causing the imbalance or the designers are already working on it.

As such, I’d rather state some hopes for the final product: I hope the solo mode will be great. I can really see myself playing this over and over again, especially if the historic events will be interesting, and I think a good functioning set of bots will be just the thing that could elevate the two player mode to where the 3-4 player experience already is. I’d also love it if World Order would turn out to be a system that gets extended over time to catch up with current world politics. Like imagine seeing something in the news and then Hegemonic Project Games a couple weeks later putting a nice PDF up for download that lets you play those events out for yourself. That would be amazing! I’d also love it if in a year or two, there would be an expansion that introduces India as a new playable global power, or maybe some faction I haven’t even thought of.

One thing I miss coming from Hegemony is the role-playing aspect of it. The cards in Hegemony were so evocative, it usually only took a few minutes before someone exclaimed “we as the working class will …”. I haven’t seen this happening in World Order so far. In a sense, that more analytical stance might be intentional. In those troubled times we are in right now, a lot of people will feel more comfortable to be an actor in a simulation rather than to personify another nation whose believe and actions they detest. I’ve already seen criticism on the net to the likes of “how can you make X a playable nation, you’re glorifying the horrible things they are doing”. Personally, I don’t think that’s happening here. World Order won’t change your stance on any of the actors in this game. It will more likely make you go “ha, so that’s why that is happening”. And even if that part doesn’t interest you at all, you’ll be left with a fun area-majority/action-efficiency/deck-building game that wouldn’t even need the player asymmetry to work. But I can understand that quite a substantial amount of players will not feel comfortable to even give World Order a try, simply because its topic hits too close to home. Maybe that’s even the best reason to do so nonetheless …

To sum it up: Although World Order is still in development, I think it’s safe to say that Hegemonic Project Games have done the unthinkable and created a worthy successor to Hegemony. It is a very different game, but the shared DNA—from the gorgeous art and the political background material to the asymmetric powers and clean mechanisms—is clearly there. I think World Order will have a hard time reaching the critical acclaim of a Hegemony, simply because Hegemony was such a singular game when it came out and because the role-playing aspect that lured so many in is missing in World Order. Instead, it will give us something even better: a gamer’s game, something we will enjoy coming back to long after the novelty aspect of its asymmetric powers has faded. The rules are easy to teach and get out of the way quickly, making World Order more approachable. There is also more immediate player agency as it is easier to grasp how to throw a spanner into another player’s carefully set up gears, something that was more subtle and indirect in Hegemony. I’m very much looking forward to more plays and how the final game (and its expansion content) will turn out. So far though: big thumbs up from my side!