Tell me if this sounds familiar: you’re browsing through Kickstarter projects, skip over a whole bunch of projects that look just plain boring or like another fulfilment disaster waiting to happen, and suddenly you stop. You’ve found a game that looks amazing! The visuals speak to you, the production is lavish, and the few sentences the Kickstarter page actually spends on telling you how the game works sound like it might be right up your alley. So you scroll past what feels like an endless display of components, skip the all too familiar peanut gallery of praising blurb writers, and brace yourself for the gut punch that is the shipping costs and taxes. Despite the latter, you’re hyped and your mouse cursor moves towards the add-pledge button but then comes to a halt: this looks too good, you think, this can’t possibly be a good game … or can it?

Crowd funding has lost much of its appeal by now as we all had our fair share of duds, games that upon fulfilment turned out to be more overproduced art pieces than enjoyable games. Having an outstanding production has actually become more of a detractor than an attractor fore me. Nowadays, anyone seems to be able to hire a sculpture and offer tons of minis or pay for artists to create gorgeous artwork. But designing a good game, that part apparently still remains hard.

So it was with a good amount of scepticism that I backed Rise & Fall back in 2022. The somewhat 90ties feeling civ-lite and hex fields gameplay sounded like it might have potential, whereas the gorgeous illustrations and tons of screen-printed meeples seemed just over the top Kickstarter nonsense. It was this odd mix that didn’t quite seem to gel that had Rise & Fall stand out to me. It felt different, worth exploring. Well, almost two years later, it was time to do exactly that … and turns out it’s actually good!

Unboxing

Usually I don’t dwell on the unboxing experience but in the case of Rise & Fall, it deserves a shoutout as it put a big smile on my face. The box is a rather reasonable extra deep ticket-to-ride box, so in contrast to a lot of other crowdfunding projects is easy to bring to a board game night. In it is a nice, sturdy, illustrated cardboard insert with flaps that cover the lower compartments. There are sheets and sheets full of cardboard terrain tiles to punch out that are extra thick and thus feel of value.

In general, Rise & Fall’s production has a luxurious but still somehow reasonable kind of feel. There are no plastic trays, no onslaught of plastic minis, no metal coins. Instead, the trays are sheets of thick paper that have to be folded to construct them. The cardboard coins are covered in foil to give them a bit of shine and the card illustrations are gorgeous. If it wouldn’t be for the tons and tons of screen printed meeples and dozens of stretch goal modules, this actually might feel like a normal game.

Speaking of which, I went for the higher pledge level where all the meeples are screen-printed instead of blank wooden pieces, and that definitely was the right choice! They look great and just using plain solid color wooden pieces would have clashed even more with the detailed illustrations on the terrain tiles than it already does. It reminded me of Kingdom Builder which’s map also was highly detailed and thus in stark contrast to the simple Catan-style houses.

Setup

The base game of Rise & Fall can be played 2-4 players, or up to 8 players if one also has a second copy with the alternate player colour scheme. Depending on player count, a certain number of terrain tiles is placed to construct the shared landscape: water as bottom layer, then plains, forest, mountain, and on top glaciers. There are very few rules to this but the result is a different map every game nonetheless. This is crucial since much of Rise & Fall is about reading the map and blocking key locations before someone else can. But more on that later.

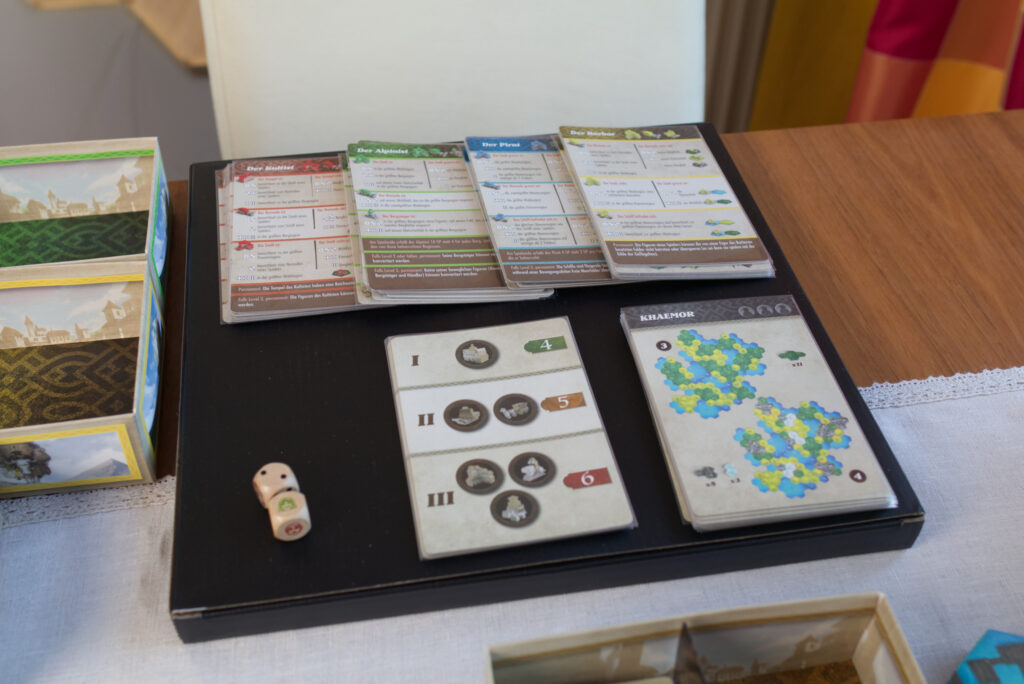

The rest of setup is pretty simple: give each player one of the cardboard trays containing their player pieces and a set of 6 large action cards. Then players choose starting positions for a ship, a city, and a nomad, the latter instantly reminding me of the settler unit in Sid Meier’s Civilization. There are no starting resources or money, but players can optionally draft guild cards which represent asymmetric special powers. These range from rather typical to what feels like game breaking upgrades. E.g. a player might have double the wood production, be able to trade resources, have less movement restrictions, or be able to destroy enemy units, something which isn’t possible at all when playing without guilds.

The nice thing about Rise & Fall’s setup is that it already puts players in a good mood. Building the landscape is fun and once you’re done, there isn’t really much else that needs to be done before being able to jump right into the game. Still, the initial positioning of the starting pieces can’t be overvalued. It is almost on a Catan-style level where one wrong placement can create a major disadvantage that is next to impossible to compensate throughout the rest of the game. Case in point: on my very first two-player play, I had placed my city a bit too optimistically along a cliff that restricts movement. Despite it being their first play, the friend I was playing with immediately placed their starting nomad right next to my city, blocking one of only two spaces the city had for expansion. This kept haunting me for the rest of the game as sure as heck there would always be some opponent piece remaining on that hex. Which might already be the perfect metaphor for Rise & Fall: looks deceptively cute but is deadly as few modern Euros are.

The Turn

Rise & Fall’s game structure is refreshingly simple and straight forward. Each player holds one card per unit type that is on the map with the cards for all other unit types remaining in a reserve. At the start of the round, each player picks one of the cards still on their hand and all simultaneously reveal their choise. In turn, each player then performs one of the multiple actions printed on the card for each of the units of that type before passing to the next player. For example, two nomads standing in forests might produce wood while another turns into a city while yet another turns into a boat.

At its core, nomads produce resources and can turn into cities while cities can produce money and create additional nomads. These are the two units that are used the most while other units can be employed based on what the situation and the map layout require. Nomads can turn into ships which both allow expanding across water and produce profit from coastal cities. As an alternative, a nomad can turn into merchants which can travel far distances and gain money from cities, or they can turn into mountaineers that can traverse even difficult terrain. The sixth unit type is the monastery which can convert enemy units into own ones.

Note that there is no combat system at all to remove enemy units which makes positional play essential. It’s quite easy to block others off parts of the map by placing 1-2 cities in the right location or prevent someone from even reaching a key lake by claiming the few plains hex fields where nomads could turn into ships. There are a number of movement and settlement restrictions in play to facilitate this. Most importantly, a nomad cannot move over cliffs (from a plains two levels up on to a mountain hex or vice versa) or into glacier hexes. Ships are the only unit that can move on water hexes, nomads and mountaineers cannot pass enemy units, and nomads are blocked by anything that isn’t an empty hex.

The movement restrictions are quick to internalize as they are also illustrated on the respective card actions. What is quite easy to overlook though are the transformation restrictions. For example, a nomad cannot build a city on a mountain but can build a monastery only on plains and mountains, not in forests. While this is also illustrated on the cards, it is done in a way that it still happened by accident at least once in every game I played so far.

Timing Is Crucial

Suffice to say, a player’s turn is one giant positional puzzle: where to move, what to block, where to stay and gain resources or earn money? It also turns into a timing puzzle because of the way the card action mechanism has been designed. For starters, a player can only pick up their discarded (=used) cards once their hand is empty, so other players can track that an opponent might not be able to move their ships again for two more turns. Turning a nomad into a different unit type also means the player will get the respective action card on to their hand, slowing down their card cycle. Getting rid of all units of a type (e.g. turn all ships into nomads) returns that card to the reserve and speeds up the card cycle.

This naturally leads players to optimize to only two or even one active unit type, especially during the early game where a rapid production of cities and nomads is vital. But also in the late game it can happen that one player for example only keeps the merchants as active unit and pushes for an economic victory. This comes at a risk though: whenever the first player builds their last unit of any particular type (e.g. all 3 mountaineers, all 5 ships), that player gains a trophy worth a healthy amount of VP at the end of the game. It also forces each player to remove one card and place it in a special area on the trophy board. Cards in that area don’t score any VP at the end of the game but more importantly make it impossible for that player to activate their units whilst the card remains there. At the end of the round, players can buy back cards for an ever increasing price, and since money is converted to VP, this starts to hurt sooner or later. For those ultra optimizers that play with only a single active card though, it can actually lose them the game. A player is out of the game if they don’t have enough cards to remove one for each trophy awarded that round or enough money to at least end up with one card in their hand or discard pile.

The hand of cards also interacts with turn order in an interesting way in that the start player moves to the left if any player has no cards on their hand at the end of a turn. Note that this happens after potentially buying back a card from the trophy board, giving players agency to manipulated turn order in interesting and unexpected ways.

Game End

The trophies are also the timer of the game. In a standard game, the game ends when the fourth trophy has been awarded where five of six trophies are used as goal for a longer game. While this opens up possibilities to rush the game and thus control the pacing, it can also lead to the game dragging out because no one is interested in trophies and follows other strategies.

It is to be seen how this will turn out over repeated plays and with more experience, but in my plays so far, we often reached a point where midway through the game we had a clear winner as the others had failed to switch to appropriate counter strategies in time. In one case for example, one of the players had figured out that cities were so densely packed that he could earn heaps of money with a merchant-heavy strategy. He got rid of all cards except the merchant and then started reaping obscene amounts of money (and thus VP) each turn. It was too late when I realized that I could have managed to gain two trophies in the same turn and thus could have kicked him out of the game completely!

Final scoring is a bit involved. Every 2 money are converted to a VP (allowing for players to go for an economy-heavy strategy), every player scores the trophies they gained, for each action card in their hand or discard (not on the trophy board), they can VP depending on how many units they have build, and finally dominance on the map is scored. For each region of the same terrain type, the player that holds the majority of pieces gets a certain amount of points. While possible points by dominance vary with the maps characteristics of course, in general this is the major source of VP one doesn’t want to miss out on, again strengthening how important positional play is.

Interaction of Mechanisms

One thing that stood out to me was how many interesting ideas and options developed from Rise & Falls rather slim set of rules. Things like intentionally gaining a trophy to get rid of a card in your discard only to buy it back immediately because the card goes back into your hand (thus avoiding the need to first empty out the hand of cards). Or getting rid of your last ship to remove that action card from your hand and thus triggering an earlier change of start players and be able to do something before the player sitting you your right.

Interesting implications deriving from a simple set of rules is something that to this extend I have only experienced in Splotter games lately. Both are also akin in how easy it is to kick yourself out of the competition, though Splotter’s designs in general feel much better polished to me where Rise & Fall has a lot of rough edges. It definitely is an interesting system to play in but I expect a substantial portion of players to lose interest in Rise & Fall after their first play left them frustrated.

Fulfillment Issues

Something else that will likely hurt Rise & Fall’s reception are a number of fulfillment issues that seem to plague the campaign. Despite lots of packaging foam around pieces, it seems quite common to at least have some piece arrive damaged. In most cases that can easily be fixed with super glue though. In my case, two of the mountaineer riders came disjoint from their bottom parts, with one of those bottom parts completely missing. Publisher Ludically seems to be a bit overwhelmed with the fulfilment with quite a number of people reporting slow or no response for requests to get replacements parts.

There was also an issue after the end of the campaign where players that had added the optional solo/co-op campaign where unaware of the fact that they had to re-add it once the funds were transferred over to Gamefound for fulfilment. Unfortunately, publisher Ludically has stayed rather silent on the BGG forums if/when there will be a way to buy the add-on. While designer Christophe Boelinger is active answering rules questions, Ludically seems to be solely focused on completing fulfillment and is way less active in communication. Hopefully this improves once fulfilment is done.

Solo/Co-Op Add-On

I was quite surprised when I first learned that Rise & Fall’s solo mode wouldn’t come included in the base game. Solo modes are nowadays such a common feature, it’s an interesting to see someone going against the stream. Designing a good solo mode takes a lot of development effort though, so charging for it seems fair.

The add-on contains four small automa decks, some recommended maps, two dice, and goal cards that force the human player to go for certain trophies. All components come in a non-descriptive black cardboard box that is almost comically large, probably to be able to have the rules come in the same format as the base game. It’s basically a throwaway as it’s possible to fit the content into the base game.

The automa operate by flipping the top card of their deck, checking what unit type is indicated in the top corner and then read the actions top to bottom for the first one that is possible / which condition applies. There are four characters: the barbarian mainly produces nomads, moves them towards the human player and then uses its special power to destroy the human’s units. The climber builds mountaineers to then claim mountain/glacier regions. The pirate tries to dominate sea regions and destroys the human player’s ships as well as plunders plains the player has nomads on. Finally the cultist has an extended range for conversion around its monasteries and can even convert cities, something that is not possible for human players.

I’ve for a long time been vocal about how much giving automa character adds in terms of replayability and increases engagement of the human player, and this is another great example. For Rise & Fall, each automa’s cards are also marked with a number between one and three, allowing adjusting their difficulty by adding or removing certain cards.

The main issue with this solo mode – besides a lot of ambiguities and rules questions – is that it’s next to impossible to create an automa that is simple to use yet can capture all the intricacies of decision making a player would do in such an interactive game as Rise & Fall. The end result is that playing against the automa feels very much like simply playing two handed but with one arm tied behind your back. For example, there are no instructions which of multiple units to perform first in a turn while that order can make a huge difference. Even for the same turn, in one order, it might result in the automa efficiently building new cities, in another it might cause it to do moves that make no sense or revert things it did in previous rounds. Even within a single action of a single unit, there are often multiple options for unit placement. The solution used here is to add a die that shows three green smiling faces and red frowning ones. The human player is to pick one option, role the die, and if a face comes up pick another one.

Then there are the trophy goals where some combinations are almost impossible to achieve before a particular automa gets them (e.g. building five ships before the pirate has them or 3 mountaineers before the climber gets them). The automa also don’t actively pursue trophies which can make the game drag on a bit. The result of all of this is that the competitiveness of the automa can range between laughable and overkill, especially considering they can do things no human player can do. In an effort to compensate the automa’s super powers, the human player is allowed to draft a few guild abilities.

While it is great to be able to play Rise & Fall solo at all, pretty much all my plays left a bitter aftertaste in my mouth and I aborted a number of them. My favourite way to play is against two automa (in the hopes at least one of them does something smart) and with a number of tweaks I posted, but I feel I won’t play it solo anymore in the future. The multiplayer experience is so much more compelling and the solo so swingy in difficulty, I’ll rather play a different game that has a consistent solo experience.

Stretch Goals

To make it short: there are tons and I haven’t played with any of them yet. So far we haven’t felt the need to add anything to the base game and unfortunately none of them come with solo rules. They all seem to be throw-in modules that can be combined at will, like adding a dragon or sea monster that roam the lands.

Conclusion

Despite fulfilment issues and a solo mode that left me wanting, Rise & Fall is one of very few crowd funding projects I’ve received in recent history where I actually felt I supported a great game and got my money’s worth. There have been so many games with great looking components, plastic trays, metal coins, or hordes of YouTubers “excited” about them that turned out to be mediocre at best that I find it refreshing to be pleasantly surprised by a game I crowdfunded. There is much to like about Rise & Fall: short rules producing more interesting decision points than one might initially expect, reasonable play time, reasonable box size, high player interaction, quick setup, a dynamic map that offers much variability, and of course lots and lots of great looking wooden meeples.

In many aspects, Rise & Fall feels outright old school. The 3D landscape reminded me instantly of Kramer/Kiesling’s Java, the card-action mechanism in a remote way of games like Concordia, the no-guardrails design philosophy of Splotter games. It also feels like a game that is designed to be played over and over again, to derive moves and counter moves, to be able to read the map and figure out whether one strategic path or the other is more viable. Both aspects will likely limit Rise & Fall’s potential audience as many player’s nowadays expect a smoother playing experience that immediately hits on first play rather than something that contains a chance for player elimination and requires multiple plays. Rise & Fall feels rawer than your average modern release, from the big range of usefulness of the guild cards to the lack of any mechanisms to catch up for mistakes in the early game. If the game system of those 6 unit types remains solid/stable enough to warrant all those repeated plays remains to be seen, it is too early to tell. In one game, monasteries seemed overpowered, in the next ships, in the next merchants … which kind of is a good sign. Same for the number of times where I later realised I could have done something different or used one of the game’s effects in a slightly different way.

Personally, I find the contrast between the high-end painterly illustrations of the terrain and guild cards vs the abstract wooden pieces a bit too stark. It doesn’t quite blend together as much as I would like, but this is a matter of taste. Same for the box cover where the title seems a bit at odds with the rest of the cover. But as you can see, I’m already nitpicking here. From a great unboxing experience to interesting first plays, Rise & Fall has me excited for more plays and actually throwing in some of those stretch goal modules. With SPIEL Essen coming up soon, table time will be limited for a while and I’m not sure when I will have time to get Rise & Fall back to the table. But since it definitely offers something unique and different compared to many other games, it has earned a place in my collection and the question is not if I will return to it, only when. I really wished the automa would function more consistently and the stretch goals would be solo-compatible. That would have been an awesome solo experience.

If Rise & Fall is for you mainly depends on whether or not you like positional/blocking/area majority types of interaction in games and if you’re okay that a game might be lost for you halfway through the game. This is not a civ-game or something where you build up a well running engine. It’s all about efficiency, timing, and most of all reading the board state correctly. Your very first move of placing your initial pieces might already be your end.