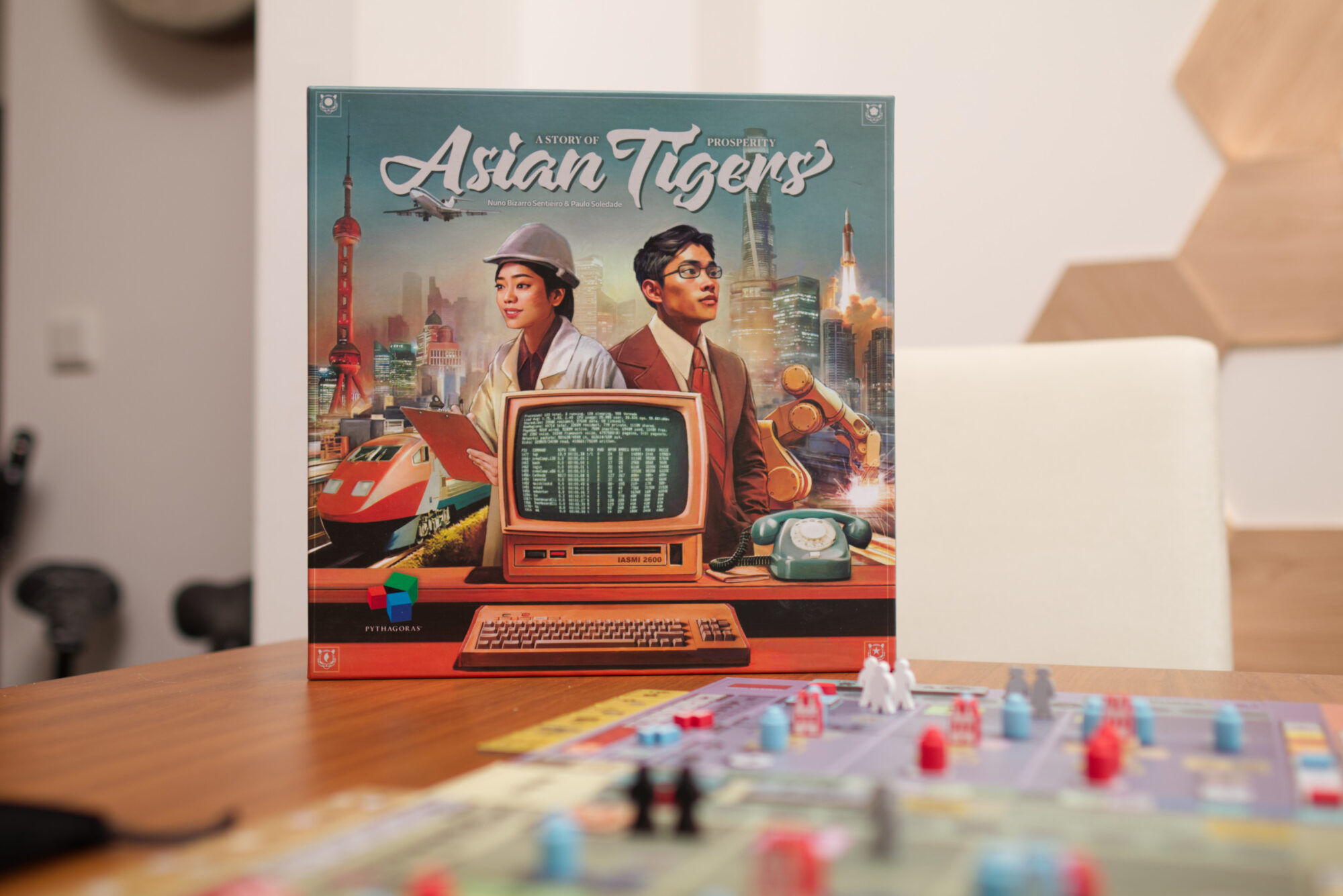

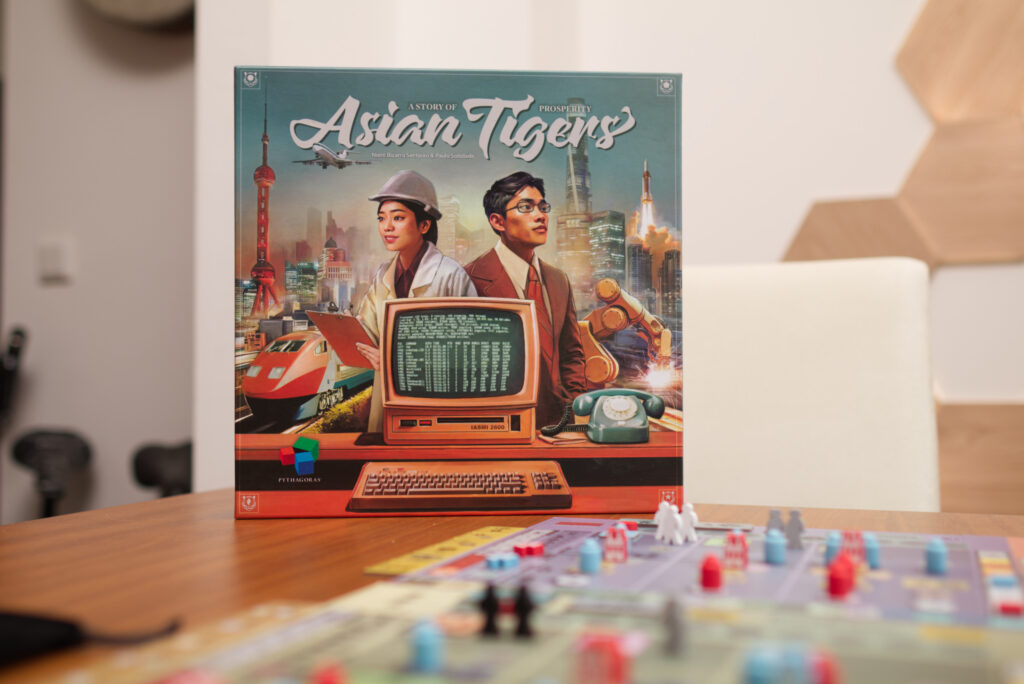

When a friend asked me whether I could pick up a copy of Asian Tigers for them while I was at SPIEL Essen 2024, my first thought was: why haven’t I heard about this game? My second thought – after looking up picture on BoardGameGeek – was: of all the games available, you want me to get you that one?

We’re living in a time where table presence and visual appearance is likely the primary factor why someone will initially get interested in a game. As much as I like writing about games, YouTube has definitely pushed written reviews into a niche and crowd funding usually sells games by great concept renders more than by great gameplay. Instagram is also a source of inspiration for many, again focusing on the visual aspects. Thus having a game where the mainboard contains no single piece of painted art but solely consist of clipart iconography, numbers, and gradients is definitely a daring choice. If that means all the development effort went into making the gameplay as great as it can be, I’d definitely be up for it. But does it?

Setup

Upon unboxing and setting up the game, it immediately becomes apparent that Asian Tigers is an odd production. The main board does not unfold but instead has to be assembled from six puzzle pieces, something I haven’t seen in years. To not make things too easy for the players, the only hint which side is the one for 3-4 player and which the one for 1-2 players can be found on the center pieces, implicitly via the turn order track on the top piece and explicitly by tiny dots on the bottom one. There is also no hint in the rules that these are the visual indicators and where to find them. The side-pieces then have to be deduced by the way the puzzle pieces are cut. It’s not horrible, but an early indicator of a) usability issues throughout the game and b) Asian Tigers making it unnecessarily hard for me to like it. It’s annoying, easily avoidable.

There isn’t much set up to be done on the main board though: in each of the four countries, a random scoring tile, bonus tile and a few markers on various tracks are placed. Otherwise one may have to remove a couple of flag tiles depending on player count and place the rest on the markets in the middle. The most interesting part is the initial seeding of workers that come in three colours: white, grey, and black. Each of the four countries has three columns (or officially called investment centres A, B, and C) where players during the course of the game perform their actions. As part of setup, one worker per color is mixed and then one placed each in the top three most valuable countries based on their scoring tile, in column A for the most lucrative, B in the second most lucrative, and C in the third most lucrative. The least lucrative country starts with no worker in it. But we’ll come to what these mean in a second.

Then there are the player boards which shows various locations where wooden components have to be placed during setup. Not only is it a lot, not only are the main pieces cylindrical and easily topple over or roll off the table, not only is the production quality so bad that multiple pieces came damaged, with their top cut off, or wobble, some pieces even cover information under them. At this point, I was a bit stumped. It felt like I had traveled back 30 years in time, all it needed was that the boards to be in black and white and the print quality worse. Maybe the “retro” vibe was intentional?

Most importantly, each player gets a small bag containing four workers of each colour from which they draw ten and place them in the order drawn on a track at the top of their player board. This will be the order in which the player has to use their workers, one by one.

Overall setup isn’t too bad once you know the game, but on first play it is a bit odd of an experience. One thing is for sure: the cover on the box definitely doesn’t match the game on the inside.

The Turn

Asian Tigers is played over two eras where basically the same happens except for an intermediate scoring at the end of era 1 and the full endgame scoring at the end of era 2. At the start of each era, the players each will know the order and colour of their ten works and as well as that of their opponents. When it’s a players turn, they take the leftmost remaining worker and place it either in one of the 3 columns inside one of the four countries or on a market in the middle of the board. Let’s start with the countries.

Each of the four countries is structurally exactly the same: There are the three columns A, B, and C, each containing a good that can be sold at the top, some spots for infrastructure to be built that we can mostly gloss for this discussion, a space for a factory to be built, a matching power plant and finally a laboratory at the bottom. For the 2p side, it’s fewer spaces, for the 3-4p it’s more, but the general column structure remains the same.

If a player wants to build new infrastructure in a country, they must place their worker in the column that already has workers of the same colour in it. If a column is still empty, they can place any colour of worker there that isn’t already assigned to another column in that country. So at the end of the era, each column has exactly one colour assigned and no two columns will have the same colour. The main difference between the columns is that column A costs 3 investment funds to build in, B costs 2, and C costs 1 investment fund. That’s the other constraint a player has: each player starts with 6 investment funds per country as represented by the track at the top of each country. When they build something, they move their marker towards the left to subtract the investment funds needed and that’s basically it. Place the respective wooden piece (unlocking additional bonus effects when placing the last in a cluster as printed on the player board), get the benefit, next player. Asian Tigers functions in almost trivial micro turns, but the decision where to use the current worker is agonising nonetheless.

First and foremost, players want to gain influence in the countries and each wooden piece counts as one “investment point” in that country. There are also satellite pieces the player can unlock from their player board that will make certain types of infrastructure count double. Investment points are converted into influence during era scoring based on majorities. The next most important thing are the factories as building one will provide the player with a one-time production of two goods of that type. Those can be sold for influence or traded on the world market, more on that later. To build factories, the player needs energy and sometimes lab coats, the other currency of the game, and – you guessed it – that’s what the power plant and laboratories buildings are for. One thing to stress here is: everything only produces once at the time of building. So for example a power plant doesn’t produce energy each turn or each era, only once.

That combination of trying to gain majority of influence and producing goods while having a limited amount of investment points and a pre-described order of workers is at the very heart of Asian Tigers. The players have to figure out what’s the best thing to do with colour of worker they have for their turn. Placing the worker in a yet empty column assigns it to that worker’s colour for the rest of the era and might cause huge problems for someone else. For example, if an opponent only has grey and black workers available for their first couple of turns, placing a white one in the cheap column C of a country will either cause that opponent to have to wait multiple turns until their first white worker comes up (risking that other people will snatch up lucrative building spots) or spent a lot of investment points and thus be able to do less actions in that country. Later in the game when building spaces have already filled up, assigning a certain colour to a column might even effectively lock out other players from doing anything in that country except with that matching colour.

It’s hard to describe, but seeing another player place the wrong-for-you coloured worker somewhere you wanted to go is pure agony. Suddenly it can be that one colour of worker has become highly valuable for you and you simply don’t have enough of them to achieve everything you needed while other colours have become almost useless. In other situations, you can use the knowledge of no other player getting a grey worker for the next two turns to act more efficient yourself, e.g. first building a power plant that makes building a factory cheaper because you know no one else will be able to build that factory before you.

World Market

A separate part of the main board and a separate mechanism is trading on the world market. This can be done again by placing a worker into one of the three markets, respecting the same placement rules as with the country columns (match colour, no colour in more than one market). Trading at the global market converts goods into flags and trade points. The latter simply means moving up on the respective track.

The flags themselves can be slotted into one of six rows to the right of the player board. These represent end game scoring multipliers, e.g. providing a VP per country you have a power plant in multiplied by the number of stars on flags in that row. Slotting in a flag also provides a welcome one-time bonus such as 2 energy or 3 influence in a country.

Eras and Scoring

During both of the two eras, players use their randomly drawn order of workers to build infrastructure, maximise influence, produce goods, and trade for flags on the world market. At the end of era one, turn order changes based on trade points the players have collected on the global market, additional influence is awarded per country based on who currently has majority of infrastructure in it, and investment funds are reset to six plus an extra fund per laboratory a player has build in a country. No victory points are awarded at this stage.

With the intermediate scoring done, all workers are removed and three initial once placed like during setup, each player again puts 4 of each colour in their bag, draws 10, and then basically do the same as in era one but with a good portion of the building spots already taken.

At the end of era 2 is where all that hard work and influence is finally converted into victory points. Again the player with the most infrastructure in a country gets additional influence points before players get VP based on the scoring tile for that country and their order in influence. E.g. first player gets 20 VP, second 12VP, third …

Then those end-game multipliers represented by the rows and flags to the right of the player boards are scored. Most importantly, it’s always the number of countries someone has achieved something in, not the total amount of infrastructure. E.g. one VP per star on a flag per country the player has build a laboratory in, regardless of how many they have build in total. So to score well here, one wants to ideally be everywhere. Finally, the number of different nations one has traded with on the global market is multiplied by a factor based on how far up the player has gone on the global market track. Whoever has the most points wins.

Solo Mode

Asian Tigers’ solo mode comes in the form of a rather straight forward automa: there is a stack of priority tiles and each turn one is revealed that indicates what and where the automa builds or trades. E.g. try to build a power plant in the yellow or blue country, whichever the automa has currently more influence in. The automa still has a randomly drawn selection of workers for the era, same as the human player, and has to comply with the same worker placement rules. It however completely ignores what the human player is doing and for example doesn’t prioritise building factories that have gotten cheaper to build because of an adjacent power plant. It also doesn’t require investment funds, energy, or lab coats to build and gets goods for free whenever it wants to sell them or trade with them.

The automa comes with a special player board that is similar to the one humans use and unlocks certain bonuses (e.g. satellites) once a number of infrastructure meeples have been built. There are also so called campaign tiles which can optionally be used to give the human player an additional goal to achieve (e.g. win while having built five power plants). That’s pretty much it. It works, is quick to execute, but of course can’t really capture the intensity of decisions when playing against human players.

Conclusion

Asian Tigers is a strange and unusual game in many aspects, starting off from that odd, uncanny looking cover and the poor production quality. The rules unfortunately aren’t great either and I was glad to have that friend of mine teach the game to me after digging through videos to make sense of it all. There were many aspects that led me to being almost totally uninterested in Asian Tigers before playing this game, chief of which is the high level of abstraction. There is nothing on the board that gives the countries character and they are all just abstract, interchangeable boxes with goods and factories in them. If the board would have been some beautifully illustrated map, it really would have helped to instil at least a little bit of theme. The way it is though, it’s as abstract an experience as can be.

It was thus quite surprising to me that we actually had a good time with our first play. The high level of player interaction and that clever worker placement mechanism really does a lot of the heavy lifting. You’re agonising over things like your next black worker only coming up 5 turns down the line, someone placing a grey one in a column where it hurts you, you having to carefully plan out which workers to use where so you’ll be able to trade in the right markets towards the end of the era, and so on. It’s a puzzle I haven’t seen in such a distilled form before and it didn’t leave my brain for long after the game was over. It’s a game that with its micro-turns gets out of the way quickly and leaves an empty floor for players to mess with each other and vie for control of the different countries.

Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to come much reason to be excited after that very first play. The only thing in the setup that is variable is which country has which scoring and bonus tile. But since the countries are largely interchangeable anyway, that really doesn’t do that much to add to the replayability. Especially when playing solo, it becomes apparent how trivial the actions are once one has figured out the worker-placement puzzle for that turn. Deciding where the current worker needs to go takes a bit and one needs to plan ahead what to do with the rest of the workers in an era, but the action itself is underwhelming: figure out from which cluster on the player board to take a piece, place infrastructure, gain bonus, done, next player.

I like games that have me actively track what other players can and can’t do, throw a wrench in their carefully designed engine, and so on. Carnegie is good recent example of even Euro games having you sit on the edge of your seat and looking over your opponents’ boards all the time. Asian Tigers though feels like the designers found the right core mechanism for interactivity but not the foundation or reason that makes it all worth it. I don’t care about my factories or power plants, they are just means to get a quick one-time shot of resources or to have one more token to provide investment points that might get converted to influence, which might get converted to VP. There are no discernible paths of strategy to explore, no memorable moments that distinguish one play from the next.

So to sum it up, my recommendation would be to not let the ugly visuals detract you from giving this game a try. It definitely does something interesting and different … once you manage to get through the poorly written rules that is. We had a great time during our first play, but every subsequent play left me disappointed. For that reason, I think that there will be few that will want to own or even play Asian Tigers more than once or twice. You’ll really need to love abstract, pure area majority games. But then, why don’t just play for example El Grande instead? It might be old but it is still an excellent game and had a nice re-issue not that long ago. Or go full into the deep end with economic games and play Arkwright. At least there you have the feeling that you’re really investing into something, not just place pegs on a board.