The action-selection, combo-driven, point-salady Euro as a sub-genre has definitely become overcrowded in recent years. I for one had my fair share of games that worked well mechanically but were ultimately forgettable and without any stand out moments, one play being the same as the next, always leading me to the same question: why should I play this game? Why spent valuable table time on this particular game when I could be playing one of a number of outstanding games I already own?

It might have been this feeling of over-saturation that led me to almost skip on demoing Galileo Galilei while I was at SPIEL Essen 2024. Sure, the theme had its appeal, but did I need yet another of those types of Euros? Turns out the answer is yes…

Setup

Right out of the box, Galileo Galilei sets a good mood. The unusually elongated main board is beautifully illustrated, same mix of unusual and beautiful for the player boards with their swivelling telescopes, same for the large format cards showing the various discoveries players will be able to make during the course of the game. The wooden tokens – which are all screen printed – feel nicer than the average blanks to be found in many other games, producing a pleasant sense of having payed primarily for good gameplay, not unnecessary fancy components.

Besides placing various pieces on the player boards and markers on tracks on the main board, setup consists mostly of creating a deck of discoveries by stacking an certain amount of level 1, 2, and 3 cards based on player count and is thus over quickly. Other than that, a few scoring tokens have to be randomised and placed in the university area of the board, that’s it.

The Turn

The core engine of Galileo Galilei comes in the form of a swiveling telescope attached to each player board. On the raised outer ring, there are printed-on actions that stay fixed in place. When it’s a players turn, they move their telescope up 1-3 steps, any step beyond the top being counted onward from the third to the bottom action space. To symbolize this, the two bottom-most spots have an “x” on them and are of a different color. So far, so boring. However, there is a second ring of actions consisting of movable tiles right underneath the fixed actions. Not only can the player do both actions their telescope ends up pointing to, they then have to remove that tile, slot it in at the bottom of the telescope and push up all the other tiles to fill the gap thus created.

This mechanism instantly reminded me of Ark Nova, probably because the top most space of the telescope allows a player to flip one of their tiles to upgrade it to a more powerful version of itself. However, there is no element of delaying an action to make it more potent. Instead, the interplay in Galileo Galilei is more subtle. It’s all about aligning movable and non-movable action such that their combination allows the player to take full advantage of whatever the current board state and resources at hand are. As an example, I had a situation where I deliberately took an unplanned action towards the top of the telescope track just to move an action tile up out of the dead zone at the bottom, thus creating a combination where one action gave me the effect I needed to be able to use the other action. It’s a simple but neat mechanism where whatever a player – even an inexperienced one – will do, they will get some benefit. Yet the efficiency with which they do this can make a huge difference down the line.

The various actions of course come with a healthy amount of possible comboing, but let’s first focus on the other core mechanism: the inquisition. In the times of early astronomy, making big discoveries could be a risky business that puts one in conflict with the church. This is modeled by two symbols: one telling the player to gain a new inquisitor and one to move an inquisitor up the respective track on their player board. The bigger discoveries you’ll make, the more inquisitors will come to “visit you” and never leave.

At the end of their turn, a player must check if any inquisitor on their board actually moved that turn and if so, they will be interrogated. Note that just adding a new inquisitor doesn’t trigger this! Most of the steps on the small personal inquisition track come with negative values associated with them and only the rightmost step adds a meekly +1 for every inquisitor there. Whatever the sum, the player has to move that amount of steps on the inquisition track on the main board that represents the player’s overall standing with the church. This will not only provide negative or positive points at the end of the game but also instant penalties or bonuses whenever one bumps against the limits of those tracks. Luckily, it’s only -2 or +2 points irrespective of how many steps one would shoot over.

This creates something I instantly dubbed “inquisition marketing” in my head: it’s not only difficult to avoid gaining inquisitors, it’s actually something the players will want … as long as they can manage to control the amount of them. Since the inquisitor movement rewards can be found throughout the game, not having an inquisitor at all that still needs influencing can lead to wasted efficiency. If enough of them are in the positive part on your board, you’ll actually want to move one to trigger the assessment and move you up on the main board track. On the other hand having too many of them in the negative makes taking any action that results in a move of an inquisitor deadly. So players usually end up collecting 1-2 inquisitors, carefully avoiding any movement until they can combine multiple movement bonuses within a single turn.

The Actions

With the core mechanisms out of the way, let’s run through what actions players will be able to choose from. First, there are those that either give a player a new die or increases the values of those the player already got. There are three colours: red, yellow, blue, also marked with small dots on the die faces to help people whose color perception is impaired. Note that dice are never rolled, they always start off at one and are used as point trackers.

Combination of dice values and colors are used to claim discoveries, gaining a player one of those big cards that lie in the shared market on the main board, or smaller discoveries represented by additional spots towards the bottom of the cards that require only a single color and thus can often be done with a single die. Both will give players VP and sometimes new inquisitors, but smaller discoveries add a bonus printed on the player board while bigger ones gain the player the card which is added to their library of knowledge. This is neatly represented by rotating the card 90 degrees and then slotting them in towards the top of their player board, forming four ever growing tracks. A different type of action allows the player to move one of their four book tokens towards the right on those tracks, providing nice bonuses if the player collected the right big discoveries.

The rest of the actions are less fundamental: comet tokens can be placed on the main board, acting as discounts for future discoveries, quadrant tokens are a pseudo currency that can be traded in for powerful effects, and markers be moved upwards on the university tracks. The latter provide small bonuses immediately but most importantly increasing multipliers for end game scoring. What elements are scored is randomised during setup, e.g. there might be a maximum of a 4x bonus for each big discovery made and only up to 2x for comets, or some other combination in the next game.

Game End

That’s pretty much it. Of course as always I omitted a few details like the ability to trade a positively-influenced inquisitor for a new die, but at this point you should have the gist of Galileo Galilei: use the telescope to activate actions, time actions so the movable part of the action selection mechanism lines up in a way it benefits you, gain dice and increase their values to make ever bigger discoveries, all while doing managing your reputation with the inquisition and climb up on the university tracks for better end game scoring. Mix everything with a healthy dose of combo possibilities via stepping up on the university track or moving along your ever growing library and you’ve good yourself a very tasty Euro-cocktail.

The game end is triggered when the deck of new discoveries is depleted and after one more final round, end game scoring commences. Multiply the unlocked factor in the university tracks with whatever the respective scoring criteria is and then add or subtract points based on your standing with the inquisition and that’s it. A good score seems to be in the 110-130 range where only around a third usually comes from end game scoring. Scoring well in-game with the discoveries and unlocking the right multipliers at the university is of course key, but being in bad standing with the inquisition will hurt your final score: every inquisitor in the negative part on the player board track subtracts up to 8 points and the overall standing as indicated on the main board can add -10 to +10 points as well.

Variable Player Powers

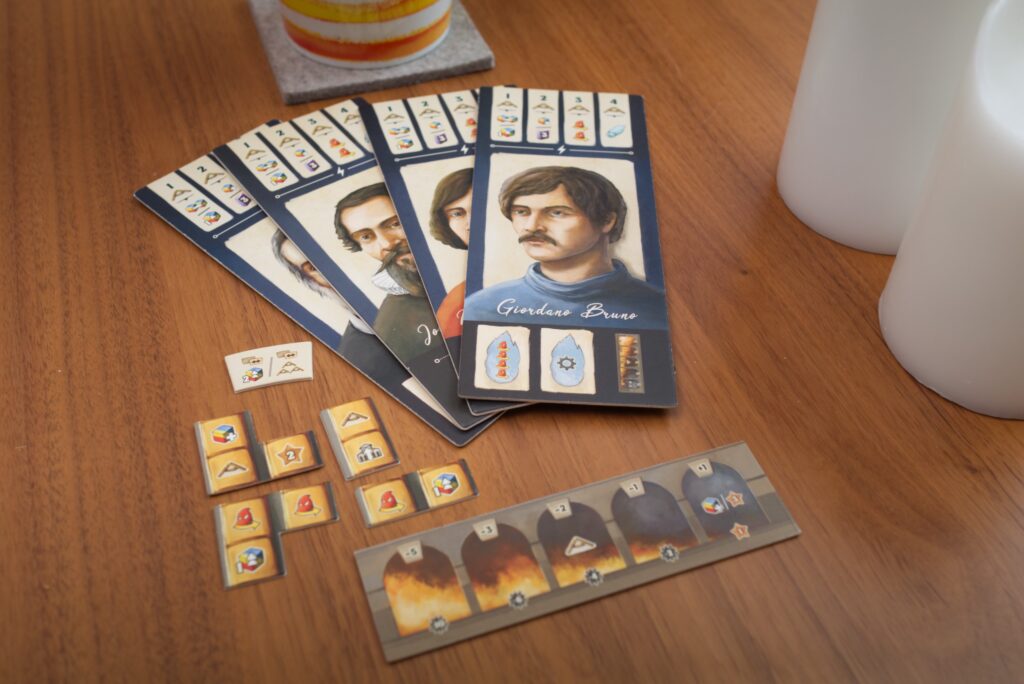

To add a bit of variety, players can optionally choose to play with unique character powers. Each of the four historic astronomers included in the game has some small bonus that actually matches their strengths in real life. Galileo can do additional discoveries, Kepler has an extra action tile and can swap positions of tiles, Copernicus has cardboard pieces he can place on his library track to improve the bonuses gained there, and Bruno has a different inquisition track that is longer but also provides bonuses when inquisitors move.

None of them are earth shattering or feel overpowered, but in an efficiency game like this, even small advantages over others have to be cleverly used to win. It’s nice that they are there, but so far I wasn’t missing anything by just playing the base game.

Solo Mode

For the solo mode however, the human player always plays with a character powers, so having them adds variety there as well. The automa itself consist of a small deck of tokens that move a marker along cardboard action tiles and wherever it lands, that tile is checked in order which of the priorities is acted upon. This happens by first checking the top row of actions and seeing if their condition printed on the left is fulfilled (e.g. does the automa have 2 inquisitors that can still be influenced, does it have x number of dice). The automa never changes die values and ignores their color, it just cares how many dice it has. That makes the automa deadly when it comes to discoveries because regardless of how many pips are needed to make a big level 3 discovery, the automa can just snatch it up if it has enough dice in its pool to trigger the discovery action.

Overall, the automa requires very little admin and is fast to use. It’s quite competitive and so far I haven’t beaten it in my three plays of solo … which is either a sign of it being balanced correctly or me just sucking at this game 😀 Based on my score in the last multiplayer game, I think I should be able to take it the next time. However, note that there is no difficulty adjustment or variety to the automa itself, just the difference from being forced to play with a random character power yourself. So replayability only comes from the random player power and the combination of what is scored how on the university tracks.

Conclusion

Galileo Galileo is a perfect example of a well executed Euro: solid core mechanisms, lovely theme that isn’t just pasted on, rewarding comboing but not to a level that it would induce AP, some element you haven’t seen as such in other games, good production, great art, quick setup, solo mode, well written rules, … In many ways, Galileo Galilei reminds me of Rococo Deluxe which is a game I enjoy just fine but mostly keep because it’s so good to introduce new people to the hobby. Galileo Galilei is perfect to a) draw new players in with its theme and artwork and b) to show them what a game that’s a little bit more thinky than what they might be used to can have in stock for them without overburdening anyone.

What stands out to me for Galileo Galilei is how well developed it is. I can’t find a single thing that feels wrong, from opening the box and reading the rules to final scoring, it’s smooth sailing all the way. And yet, there is skill. Someone that is good at efficiency-comboing will end up with 30VP more than someone who is not. The only thing I intuitively was expecting was that the card market would somehow change more dynamically, e.g. by discounting or discarding discoveries that stay in the marktet for a long time. What often seems to happen (especially in 2p games) is that you’ll finish the game with a number of level 1 discoveries on the board that no one ever bothered to do. That seemed unusual to me, but it didn’t hurt the gameplay itself. It has to be said though that Galileo Galilei is a rather multiplayer-solitaire gaming experience. The only area of real contention is the shared display of discoveries to be made and four in-game milestones for whoever fulfils a certain condition first.

In general, the game has a very good flow to it and while you are thinking about what to do on your next turn, the other players might already be done with theirs. But I noticed that besides those milestones, I wasn’t really caring much about what my opponent was doing – which might or might not be positive depending on what you are looking for in a game. Despite the inclusion of the inquisition, Galileo Galilei is definitely more a feel good game that rewards you for choosing your actions well rather than it would punish you for missing out on what your opponent is planning.

Speaking of the inquisition, the mechanism used here is quite lovely. I like the balance between players actively wanting inquisitors to influence but having to be careful to not get too many of them at a time. If you end up with three of them in your left-most spot, you’ll need to collect a lot of quadrants so that when the inquisitors inevitably move, you will be able to use the respective free action to move them even further in one go and reduce the penalty of the interrogation. The slightly disappointing part though is that after only a few games, it feels like I already explored everything there is to this game. There for example seems to be one right way to deal with the inquisitors and a no-inquisitor strategy doesn’t seem to be viable. As a result, the challenge from one game to the next feels very much the same with only the unique character powers and the university scoring multipliers pushing players slightly into different directions.

However, Galileo Galilei can be summed up well by what a friend of mine said after their first play: “oh, this is a nice one, you can keep that one”. What they meant is that I’m cycling through a lot of games each month. Part of it comes from me writing about board games, part of it is that I like this exploration phase of a game. Learning the rules, figuring out what good strategies might be, how much depth there is to a game, and so on. As a result, games come and go, and sometimes even excellent games like SETI (by same designer Tomas Holek) will leave my collection after only a few plays and without even having written about them. Galileo Galilei doesn’t have anything that makes it standout and has me rave about it, it’s not a “you must play this game right now!” kind of situation. But would I play it if someone wants to? Anytime. Is it a great game to bring to game night with my colleagues that don’t play as many games as me? Definitely. Could I play this with my mother who plays a game once a year? Sure. Will my usual group of heavy gamers enjoy it? Yes. And that, that is a real accomplishment!

Many new releases get attention because they have one outstanding aspect such as a never seen before mechanism or particularly great minis, something reviewers and gamers can latch on to. But most of them ultimately come and go because they lack in some crucial other aspect: no replay value, flaws in the game design, balancing issues, unnecessarily complexity, too light, and so on. Galileo Galilei is kind of the antithesis to that: from game design over rules to production and art, everything is done on a high level of quality and competency. Galileo Galilei didn’t have amazing hype before it came out and it doesn’t seem to have it now that it is out. It’s just a very good game. Whether you are a heavy euro gamer and enjoy a game for when you are not in the mood to play the next big Lacerda or you play with casual gamers and want to introduce them to the combo-efficiency-Euro sub-genre, Galileo Galileo is a great choice. It has the charm of a Grand Austria Hotel without the meanness, comboing without the potential AP of a Barcelona, approachability of a Rococo Deluxe … it just misses that one thing that would make it stand out more. Should that keep us from playing a game that consistently delivers a pleasant experience when put to the table? I don’t think so. In the end, being good is better than just standing out.